Guilt and blossom chase me along the mausoleum path. The guilt because I’m late, but not only that. Coming here makes me realise how badly I’ve neglected a friendship. The blossom sticks to my shoes, already fringed with brown corruption before it left the tree.

It’s been too long since I last saw Abigail Goudy.

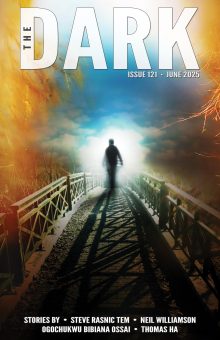

The building is an impassive example of Scottish masonic Victorian death fetish. The square sandstone base is adorned minimally with simple pillars and arches and topped by a squat tower. It’s a monument to the fundamental truths of life and death constructed with absolute precision from the simplest geometries, and built to last eternity. As I near the doors, an usher slips out. Extracting a roll-up from his pocket, he cups his hands to light it. He takes a draw, then nods companionably and steps aside to let me enter.

“How much have I missed?” I listen for music.

The usher cocks an eyebrow. “Not a thing, mate. They’ve only just finished tuning up.” He waves me inside. “Sit anywhere. There’s plenty of room.” I duck past him and his voice follows me inside. “Mind and take the bumf from the table.”

The exterior wall is thick, the ceiling low; the echoes of shoe-scuffs on stone startlingly oppressive. At the other end of the entrance passage there’s a sign:

QUIET PLEASE

TALKING IN THE AUDITORIUM IS FORBIDDEN

Next to that, a rosewood table that wouldn’t have looked out of place in my granny’s hall. It holds a stack of leaflets.

“Brochure, sir?” The words are whispered but the closest person to the table is another usher standing a good fifteen feet away. She smiles, lips glossed with cherry smugness and, maybe, an ounce of flirtation. I’d consider asking for her number, something to pass the time while I’m back in town, but she’s probably an undergrad and I can just hear the scorn in Abi’s laugh when she finds out. It’s not worth the effort. “This part of the room is a whispering gallery.” Again, the words are ear-intimate. “You can read all about it in the brochure.”

I take one of the leaflets. Single-page; the first usher had it right with bumf. On one side: a photograph of Abi, badly shot and too formal; it makes her look ill. Under the photo, a crush of text. I barely glance at it, taking in only the highlighted phrases: Ground Breaking and Daring and Rewriting The Rules of Classical Music. At the bottom, in larger type: World Premiere.

A world premiere classical music performance in a nineteenth century mausoleum could, generously, be described as fairly daring, for anyone but Abi at least. The rest is crap. Typical university production, the pamphlet clearly rushed off by some clueless intern at the last minute. Those aren’t Abi’s words. It all feels a bit . . . desperate, but then it’s been twenty something years since Alpine Pasture earned her the wunderkind tag and she always took the expectation that came with it hard.

I gift the usher a smile, turn to survey the rest of the mausoleum interior and realise that the tower that sits atop the square base is hollow all the way down. Cresting it is a dome and I can see the clouds through the cupola. Once again I’m impressed by those simple geometries. Back in the day, Abi and I would have taken much puerile glee in the fact that it looks like a stubby cock.

“Alessandro Stradella was chased through the streets of Genoa by a love rival’s assassin and brutally stabbed to death.”

This was on the smoking deck of the Chip. A June evening swelter. We’d been baking ourselves since lunchtime, guzzling lager to chill down. Roz had gone for a pee and then it was her turn at the bar. The pub was crowded. She’d be a while.

Abi was my new girlfriend’s music student flatmate. Quiet, I thought. Not the easiest to make small talk with. Maybe even a bit strange. Now, she looked pleased with her pronouncement, even if it was apropos of fuck all.

“Okay . . . ” I didn’t know who Stradella was. I rolled the heel of my glass across my forehead. It wasn’t cold enough. I wished Roz would hurry up. Not for the first time that day, my thoughts turned to fucking her when we got home.

Abi scooted closer. She was wearing a high-necked retro top, and a floaty skirt that displayed her skinny legs. She slapped my leg just below the hem of my shorts. Her fingernails were painted green. Just like Sally Bowles, I’d told her earlier but she’d dismissively claimed not to know who that was.

“Old Allesandro was a philandering bastard. Are you saying philandering bastards don’t deserve to be punished?”

Unsure where this conversation had come from, and wary of where it was heading, I opted for non-specific agreement. “Well, within the law of the time, of course,” I ventured. “I suppose that happened a while ago, eh?”

“Sixteen eighty two. He composed a lot of well-regarded work, but he fucked around just a bit too much. Naughty boy.” It happened in a single movement: one second she was sitting next to me, the next she was straddling my leg. Her face was inches from mine, her eyes sparking and, when she pushed herself against my bare thigh, I could tell she wasn’t wearing knickers. Abi kissed me, a slack smooch that tasted of beer. When she disengaged, she was smiling. “Poor Alessandro,” she whispered. “Who knows what great works he might have left us if he’d lived out his natural days. But he just couldn’t keep it in his pants.” She settled back into her original seat and smoothed out her skirt just before Roz returned with the beer.

I didn’t get to fuck Roz that night. We had a row that was probably more about the heat and the drink than anything real. Certainly, Abi’s name was not mentioned, but I couldn’t help being convinced that Roz suspected something. It was that or my own guilty conscience.

I never asked Abi why she did it. The more I got to know her afterwards, the more I learned that was just the sort of thing she did. Even so, Alessandro, and my own name, Alastair, were too close for me to accept as coincidence.

Beneath the tower, the square mausoleum floor is made into circle by a beautiful geometric mosaic. The intricate black and white pattern is currently obscured by folding chairs. In the very centre are four grand pianos, set nose-to-nose like compass-point jigsaw pieces.

The improvised auditorium is far from full. Nearest the door are a clump of journalists, identifiable by the tablets and netbooks they fuss with while they wait. As an insider I can tell you that it’s never a good sign when they begin their copy before a performance has even started. I’m supposed to be covering this too, in the hope that I can flog it to some online arts blog or other. I used to get commissioned for this malarkey but times move on, don’t they? The rest of them will hustle to get their pieces posted. I’ll at least do the composer the decency of waiting until the performance is over. My byline still carries some weight. My expertise in the subject. I didn’t even bring a notebook. For once, this is easy money.

Further round the room are the students and academics. Among them I recognise Abi’s old tutor, a spectacularly unkempt man whose name I can’t for the life of me recall. He sits with his eyes closed, as if he’s already hearing the music although, most likely, he’s napping. I don’t recognised any of Abi’s family among the remaining singletons dotted around the space. Those must be friends, maybe even fans. There aren’t many.

I take a seat. The chair scrapes, an ominously loud rasp that booms around the room, turning heads and raising a few smirks from others who have previously made the same mistake. The reverberation persists as I remove and fold my coat and then carefully sit down. And then, to my surprise, the noise of my faux pas washes back again. This impressive echo certainly explains why everyone is obeying the sign at the entrance so diligently. And it gives me the first real hint as to why Abi picked this place.

“Jean-Baptiste Lully died from a conducting injury.” She offered me this while clambering upon the outcrop that she’d gleefully christened the clit for the way it protruded at the base of the narrow vee-shaped pasture and overhung the gushing waterfall below.

“Really?” The rock was slick with spray but I refrained from warning her about it. I’d already made that mistake once. She said I sounded like her dad.

Abi reached down for the flags. “Lully was a court composer for the Sun King. In the days before they had conductors’ batons, they used a heavy staff to keep time.” She stepped onto the highest part of the rock, wobbled, and then righted herself, with the furled flags outstretched to the sides like a tightrope walker. She grinned down at me and I was momentarily dazzled by the spray and the alpine sunshine. “So there he was, beating away on his big gilded staff, and he only went and bashed his foot. The wound festered, then duly turned gangrenous. Fin de Lully.” She had her poise now, like a gymnast about to perform some feat of acrobatics. “Well . . . ?”

“What?”

She nodded towards the recording equipment waiting up the hill and I scurried off obediently. When I was in position, she raised the flags above her head. The silk fluttered like emerald sails. Then she waved them and that was the signal for me to set the recorder going, and for the tenor and the violinist a little higher up the meadow to begin their performance, and for the patient, bemused Austrian farmer way up in the high pasture to start bringing his herd down the mountainside.

Once everything was underway we lay in the grass and listened to the birdsong and the rushing water and the approaching clatter of cowbells, and to the twin melodies of Abi’s music rising into the spring air, shimmering off the mountains that ringed our little valley, colouring the air with echoes.

We weren’t a couple. We never were that. But lying in that field with the wildflowers and the insects and sounds of nature and music mixed together in that huge, natural echo chamber, we were happy.

Something hovered and droned near my head until Abi swatted it gently away. “Did you know Alban Berg died from a bee sting?” she whispered.

It says on the back of the leaflet that the mausoleum is thought to have the longest echo of any man-made building in the UK. It’s the old obsession, then.

The hoo-hah over Alpine Pasture had barely died down, its incredible twin melodies, famous already, appearing in adverts and sampled in chart music, when Abi went public to declare them worthless. “It’s not the music itself, Al,” she told me over the last of the champagne. “It’s what the music creates, what it leaves behind. They can play Alpine in the fucking Carnegie Hall from now until judgement-day-hallelujah, but they’ll never get it. The only people that ever heard it properly were you, me, Herr Krankl and twenty four cows. Listen . . . ” She played me the recording I’d made that day in Austria, skipping to the soft tailing off of the voice and violin. She made me listen until the sounds had become echoes, and then even less than that. A delicately stained atmosphere. A hue.

Abi called this the persistence of echoes. Said it stayed in the place long after the reverberations had dwindled beyond human hearing. “Music is situational, Al.” She was drunk by then but she meant what she was saying. I just didn’t know how much.

I’ve been hoping that the gap between her last outing and this new venture might have meant a rethink—the reviews of Priestland Beach had, with gleefully childish irony, labelled it a dull echo of what had gone before—but it seems not.

I look around, surprised that the composer herself hasn’t put in an appearance yet, scan the interior for that slight frame, those sparky eyes, that dirty mouth that will smile sweetly and then utter a public reprimand. “Who fucking invited you, cocksucker?” Something like that.

I’ll take it. I deserve it, half of it at least. I’m looking forward to seeing her.

For now, though, there is no sign of her. Instead, without further preamble, a young Japanese woman dressed in ubiquitous orchestra black walks along the central aisle, sits at the closest of the pianos, and begins to play.

They did perform Alpine Pasture at Carnegie Hall. By that point Abi was deeply disinterested, calling any performance of the piece pointless. I persuaded her to at least take advantage of the paid-for trip to New York for the opening night. As hoped, she took me along as her plus one.

Neither of us saw much of the city. At that time, perhaps inspired by her success, I was still trying to be a novelist, making a point of bashing away on the laptop the whole day while Abi was dragged around a succession of interviews and associated obligations. I couldn’t have left that hotel room if I’d wanted to. Writers talk about the white heat, when the hold their entire world in their head and the words simply flow. That was me that couple of days. A genius in nova. I pounded away at it until she appeared at my door in her party frock and demanded to know why I wasn’t ready.

While I washed, she hovered at the bathroom door, nosing through the running order for that night’s programme. “Alexander Scriabin died from septicemia resulting from a sore on his lip, you know.” She looked at me in the mirror. “Is your novel done yet?”

“Nearly,” I replied sulkily, unwrapping my rented tux.

I remember very little about the performance. Both of us felt restless and out of place, Abi twitching and tutting, and me frustrated at being separated from my book. I do recall very clearly the applause at the end of Alpine. A rapturous wave that stilled her for the only time that night. I think it was with terror. Later there was a reception. Abi was whisked around the gushers and the glad-handers while I made friends with the booze table. I lasted an hour before grabbing a bottle and sloping off back to the hotel.

I was still up writing when the knock came, and there was sufficient fury in it to make me jump up to answer it.

“Where the fuck did you go?” Abi stormed past me, kicking aside the suit trousers that lay on the floor. “I needed you there.”

“Sorry . . . ” I was taken aback by the force of her obvious hurt. “I was just hanging around looking stupid . . . ”

“No.” She spotted the champagne and necked a long swallow. “You were being there. Did you think I brought you along for your good?”

“I was there.” I folded my arms, aware that wearing only boxers and a Motorhead t-shirt undermined my attempt to prove my commitment, but determined to try anyway. “But I got bored, and I needed to write my fucking book.”

“This?” Abi kicked off her heels and climbed onto the bed. She dragged the laptop over and glanced at the text on the screen. “Is it brilliant? Because there’s really no point if it’s not. Brilliance is all those tossers are interested in.”

I grabbed the laptop off her and closed it. “How the fuck do I know if it’s brilliant or not?”

Abi laughed then. She could use laughter cruelly and often did, but this laugh was one of recognition. Something that came from deep inside. She got off the bed and gently took the laptop back from my petulant hands, placing it on the nightstand. Then she took another long swig of the stolen champagne and kissed me. The cold fizz that filled my mouth in one moment was driven from it in the next by Abi’s tongue, and when she pushed me back onto the bed there was such energy in her that her face glowed.

It wasn’t the first time we’d fucked, but those other occasions had been out of boredom, a need for companionship. This was something else entirely. It was sex as narrative, a savage-subtle exploration of themes of defiance and insecurity. It was sex as performance, a nuance choreography of physicality, of touch and timing. It was sex as communion, a blurring of the roles of artists and audience. Of person and person. It was physically and emotionally exhausting. I had never had a night like it, and don’t ever expect to again. Not with her, not with anyone. Abi was a virtuoso that night, and when we were done I finally fully understood what she meant when she described herself as a situationist creator. That art is its time and its place as much as it is its content.

“Do you ever worry that you’ll die before you create your masterwork?” She said this into my chest, as she curled against my side.

I don’t remember what I answered. I was preoccupied with the knowledge that she’d addressed me for the first time as an artistic equal, and I felt anything but that. I knew that I had nothing like Abi’s passion. I never would.

“I can’t decide if it would be worse dying with your greatest art still inside you,” she was mumbling now, almost asleep, “or getting to the end of your life and realising that your best came right at the beginning.”

The melody is picked out slowly, metronomically methodical. For the first ten minutes it could be something by Erik Satie, but the tune lacks the sweet delicacy of his Gymnopédies. I recognise it as a moodier—doomier—rendering of the main theme from Alpine Pasture played without character or inflection like the flattest recording of the piece. A dull echo. But that’s not all: the tempo has been chosen so that the notes mesh precisely with the mausoleum’s long echoes, the tones coming ghosting back down the chamber, layering behind the melody like contrapuntal memory. Washes of harmonics lying on top of each other like geological strata.

It’s a beautiful effect, and a clever one. It’s certainly enough to hold the attention of the audience. Looking around, I see eyes closed, half-smiles, heads nodding in appreciation. I still can’t see Abi, though. For all my laxness in keeping in touch, she’s been partly at fault too—dropping off social media, making herself hard to reach short of an actual phone call—but that’s quite different from snubbing your own premiere. Having created something this intricate, this unique, I can’t believe she wouldn’t attend the performance, but that seems to be the case. It saddens me.

The pianist repeats a cycle of interpretations of the themes, drawing different moods and colours from the space, but it becomes apparent that there’s no development going on. Just the tune and its echoes. I can hear the audience becoming restless. Someone is whispering, then someone else suppresses a sneeze and rummages in a bag for a handkerchief. There are scrapes, shifts, rustles. From the area that the journos are sitting in I hear a clear mutter: “ . . .well it’s just substandard Cage, isn’t it, really . . . ?” In answer, someone laughs. And all of these sounds come back again five, six, seven seconds later. Through the growing susurrus of impatience, the pianist keeps playing.

At almost an hour into the performance, something new happens. A second pianist, a bearded man this time but dressed identically to the first, walks down the central aisle. He sits at the opposite instrument in the cloverleaf and begins to play. The effect is shocking. An intentional, cacophonic grinding of musical gears that silences the room instantly. Not only is the new pianist playing a different tune but he is also playing out of time and, worst of all, his piano is maybe a quarter tone out of tune with the first. The two players continue as if oblivious to the music each other is making for perhaps a minute, and the relief when the female instrumentalist stops, stands and leaves is palpable. There’s a ripple of laughter in the room, but I’m listening for the new melody and am unsurprised to recognise Hangar No.1, her second major piece.

What is this Abi? A greatest hits tour?

Hangar No.1 did not play at Carnegie Hall. Given that it involved a piano and string quartet played while suspended thirty five feet up inside an aircraft hangar, and ended with all of the instruments being dropped onto concrete, it was amazing that it was ever performed more than once.

“Well, they wanted an ending,” Abi said. This time the hotel was a B&B a few miles from the Norfolk aerodrome where the premiere had taken place. One of Abi’s irks from the continuing commentary about Alpine Pasture had been the grumblings over the ninety seven seconds of silence following the final notes that she insisted must be observed as part of the performance. Apparently audiences wanted to know when to clap. She looked at me levelly. “Gimmick or not.”

“I said I took that back.” I’d tried to make a joke of it since that unguarded word had escaped my lips but she refused to let me off the hook. “It’s quite the fucking finale.” Then I realised that despite her bullishness she was looking for reassurance. It’s hard to gauge an audience reaction that consists mainly of shrieks of alarm. “It was amazing. Really.”

And then I went to hold her. Partly because I had no more words to give her and partly because I was afraid that if we continued to talk she would start nagging about the novel again. When we saw each other, she’d stopped asking about how I was; just the book, like art was the only thing one could value.

By that weekend, we’d not seen each other for a while because I was being offered increasingly steady, and lucrative, work in the south. It was my reason and my excuse. To my surprise, though, I’d not completely given up on the book. I still tooled away at it in the evenings and had even managed to interest a literary agent, but he’d had fuck all luck in selling it. I knew it wasn’t brilliant. I didn’t even know how to make it good.

We made love for the sake of it. It had become a habit of affirmation, nothing more than that. About as far from the fireworks of that night in New York as it’s possible to get. Afterwards way lay apart. Not speaking, not touching. I don’t know if she knew I was awake to hear her whisper into the darkness: “Bedřich Smetena contracted syphilis, and died in an asylum of a progressive paralysis.”

There was no exploding piano at the end of this rendition of Hangar No.1. Just another jarring, out-of-tune changeover to the next pianist. The following hour was variations on the melodies from Celestine, which I knew to be an achingly gorgeous thing that flowed like water, but was now rendered heavy-handed and robotic.

We’re now well into the fourth hour. The journos are long gone and more than half the audience too. A while ago I heard someone whisper something to the attendant. Some seconds later, the building’s echo relayed it to my ears among the piano reflections: “How long does this thing go on for?”

“They haven’t told us, sir,” came the shimmering reply. “The mausolem is booked indefinitely.”

I, though, know it won’t be long. They’re on to Priestland Beach now. The fourth and last of Abi’s major pieces and, while as gorgeous as the rest, my least favourite because it’s the one we’d rowed over. Hangar No.1 came out a year after Alpine, but there was then a gap of several years before the world saw Celestine. Abi had filled her time with short pieces, with theatre music, scores for friends’ indie films. None of these she put her name to. Sketches, she called them. Which was all very well, but she had a label with a schedule to fulfil, publishing and distribution deals. She despised it all, the industry, but promised to deliver more promptly in future. When Priestland Beach was ready, she made absolutely sure that her already all-but-burned bridges were reduced to smoking rubble by declaring that there were to be no recordings or concert performances of the piece. There was no point, she said. They could never replicate the experience of being there, the echo profile of those towering slate cliffs.

As a friend, I’d tried to reason her around. “What are you going to do for money?”

“Money?” She was genuinely astounded that I should ask such a thing. “Hark at you, Mister Work-for-hire. What are you going to do for time?” She screwed her face up, suddenly pugnacious. “How long do you think you have to dick around? How many tries to get it right? You want to be like poor old Alkan? His fucking coat stand fell on him.”

We’d already begun to, but after that we drifted increasingly apart. At birthdays and Christmases, I used to send her those hideous cards that played tinny little tunes when you opened them. They transmuted into e-cards, and then Facebook messages. After she moved off of social media, with no one to nag me, I quietly and conveniently forgot I’d ever attempted to be a novelist. This is the thing Abi never understood. It’s how most attempts to make art end. Failure, or, at best, mediocrity—which in her eyes was the same thing.

Listening to Priestland Beach, its echoes washing back and forth like the sea waves on that bitterly cold day when it was first, and last, performed, I acknowledge that I’ve missed Abi like fuck. I’ve always missed her. Every single day. The guilt gnaws at me afresh, and I discover that I’m also mightily pissed off. At myself, at her, at both of us for letting this happen. I want to take her by the arm and usher her outside right now and tell her that I’m angry and I’m sorry, and that we should both make a bloody effort to spend more time together. But she’s not here, is she?

I extract the leaflet from my coat pocket and smooth it out, thinking perhaps that I’ve missed some detail, like this is a second performance and I should have been here for the matinee instead when the room was a sell-out and ovations echoed up and down the length of this odd, old building. I scan the blurb and then I see the thing I missed before. In my arrogance, my familiarity. In my expectation that she would always be there when it suited me to look for her.

The past tense.

The prose is ham-fisted but it clearly mentions an illness—an impressively rare one, apparently borne bravely, and alone, while she worked to complete this final composition. I drop the leaflet on the floor and bow my head into my hands and, while it sinks in, the pianos continue to play. And play. Sometimes it’s two of them together, sometimes three, sometimes all of them. It’s no longer noise to me, it is memory. Echoes, layers and hues.

—We’re in the hangar, laughing at the pianist’s fear of heights.

—We’re noisily manhandling the tubular bells down the cliff path to the beach, gulls wheeling around us.

—We’re setting up seventeen glockenspiels along the length of a road tunnel at four in the morning.

—We’re holding each other hard in New York. She doesn’t know that I’m crying into her hair.

—We’re lying in the alpine grass, holding hands under the bluest sky.

—She’s chiding me about Ravel, Chausson, Purcell. Taxi crash, rode his bike into a wall, drank bad chocolate.

The music, her music, all of it. Mechanised, dehumanised, rolling on relentlessly, perhaps forever, but I remember how it really was.

“Abigail Goudy died of a broken heart.”

This is not a memory. It is sung. A soft, mezzo line that weaves through the melee like a silver thread, riding the echoes once, twice, three times until it is inaudible. I snatch my head up but there is no singer. Just the four pianists, the bored attendant, and me. It’s got dark. Everyone looks tired. I realise I’m shivering, shaking. There’s a blanket around my shoulders and a prepacked egg sandwich on the chair next to me. I have no idea how much time has passed.

I look at my hands. They’re the hands of someone who has drifted into middle age unaware. Something at floor level catches my eye. Something white on my shoe, a perfect blossom flower. It is ringed with brown corruption.

Without a word I rise and leave the mausoleum and, as soon as I am outside, the music ceases.

But the echoes linger.

Originally published in Secret Language, a collection