i.

He visited me in the night, carrying his head.

Dead men would sometimes visit the city this way.

I had known this could happen with the executed, but I could not bring myself to accept the visitation. Yet there he was, in my apartment: holding his severed head just above the waist, eyes open and unblinking, before the mouth spoke its first word.

“Yes,” said the head, as though answering questions that went unasked, smiling like we had settled some inconsequential misunderstanding, and it filled me with an inexplicable, if strange, relief.

xiii.

You led us here, without knowing what you knew. But ruin can be rebirth, if you remember this place. Look beyond the glass, and I will bring you too. Beyond the glass where they hide, the end of their reign.

ii.

Like many in the city, I had not slept for some time.

Fewer and fewer of us had been able to sleep as the seasons changed. The windows of our buildings were infested with the sleepless looking out at the sleepless. Many feared, or simply accepted, that we were slowly going insane.

The dead man in my apartment carried his head and followed me on my nightly walk, and during those sleepless hours, he and I looked at the windows together, watching the faces of the sleepless staring back as we went.

“You have my sympathy, for your . . . state,” I finally said, without fully knowing why. It felt true, if nothing else, in that moment, I supposed. Most in the city felt some sympathy for the executed, even though we carried no direct responsibility.

We knew vaguely there were many awaiting execution at the derricks outside the city. Many dead, and not all of them with the privilege of carrying their heads into the city like this.

“Do you ever express your sympathy for those like me . . . ” He smiled. “Before it is too late for the sympathy to have effect?”

The dead man already knew, of course, that the answer was no.

xii.

The headless break the gate. All together, they break through. Not stone or wood or metal. The Bodies break the glass. The Minds break the glass. The fortress ahead and the city behind, reflected. All the same, in the end. Forward, backward. Through the gate, together, say all of you.

iii.

I knew that Enemies of the city were always executed, and we had many Enemies here.

People from other places trying to enter our city. People from this place who strayed and failed to follow our laws. One by one they were sentenced and escorted down the avenues to the distant derricks.

Even as children, we knew, somewhere, they were being dealt with after sentencing. But how exactly the city dealt with Enemies was not known. They said there were executioners, men who wore special masks and robes, so that they could not be observed in the lightless penumbra of the leaning derricks.

No one witnessed the ones effectuating the executions on the gallow roads. But in one fell swoop, one lever pull or one catch release, whatever the mechanism of the beheadings, they dealt with Enemies, in ways certain and unseen.

Unseen death was preferred because it met no resistance, by design.

The dead man with me said he had not noticed the exact means of his execution nor anticipated its arrival. One moment, he had been in chains and made to march out to the distant derricks by the city watchmen. The next, he had been beheaded mid-stride, as if by the wind.

“That was it,” he recalled, “then I was free.”

“Free.” I found that such an interesting choice of word.

xi.

Giants overtaken, ribs broken apart. Fires burning walls into sweating streams of sand. Thundering sounds of things much larger being toppled, one by one. Cries from the concealed, hiding, with nowhere to escape. All of it to come apart soon. All of it, apart.

iv.

The dead man and I passed the covered tumbrels and stopped to observe the children behind bars. Each delinquent held below the artists’ quarter told stories to the sleepless passersby.

I did not know how I decided who I would give a coin to each evening.

I tried to direct my charity in a way that felt fair. Sometimes I would choose a child that had brothers and sisters waiting in the workhouses. Sometimes I chose a child who professed a passion for a promising career, if given another chance. Sometimes I chose one who reminded me of someone I knew. Sometimes I simply chose among the ones most like myself.

The children would buy their way out of the cages, eventually. Work off their debt and delay their sentencing as Enemies; that was, at least, the hope.

The small boy I had chosen that evening took a coin from me gratefully, his rough fingers touching my soft uncalloused palms.

The dead man lifted his head to better look at the caged and then at me, studying my features in the lamplight.

“Surely you have more than one coin to give?” he questioned.

“I may, but there is need to restrain my charity,” I explained. “I would quickly run out, and without, I’d soon be in the tumbrels, too.”

“How about two coins, then?” the head pressed. “It’s only one more than one.”

The eyes behind the bars looked up at me.

“Three coins? Four? Surely four would not send you into straits.”

I did not know what to say and so remained silent.

“Let me ask this instead: Have you ever given enough in total, one coin at a time, to one child, to erase a debt? One child, one debt, ever anything like that?”

“No,” I admitted. I had never done that. Of course, I had no way of knowing if any settled their debts. But I knew all the coins I had given combined were not enough for even one debt.

“So is the single coin at a time for them, in the end, or for you?”

I did not want to reply, especially where the children could hear. Some of them began to cry as tall watchmen wheeled carts away.

x.

There are too many to stop. Too many to fight. Running from the gallow roads and across the plains, from every direction. Others ahead of you, and others behind. Closer, growing closer. Too many, and they can’t stop us all.

v.

We continued on, and the dead man spoke more of his own execution. He did so very casually, as though describing a beneficial divorce.

“Sometimes the Mind interferes with the Body, and thoughts can be a hindrance. Other times, the Body interferes with the Mind, and needs can be a hindrance. But now we speak separately and yet together, Mind and Body. Apart and yet one.”

I did not understand.

“In death, the Body senses out of time, out of order, in advance when receptive. It heeds things in prophetic ways before the Mind is even aware. And the dead Mind can direct the Body with unbreakable purpose and calculation with the right knowledge. You are a gift to one another, if you can relearn your relation. One does not go before the other. Together, that’s the way we all go. Perhaps you can hear your Body speaking already?”

I could not, at that moment, and would not know what to listen for.

The head of the dead man gazed upward lovingly at the arms that carried it, toward the shoulders and the neck where it had once resided. His body seemed silently to gaze back at the head. If they were speaking to one another, then, I could not hear the exchange.

We went farther along the avenue, and under flickering lamplights, we saw a long procession from the courthouses across the rotary. Enemies walked in shackles, directed by tall watchmen away from the heart of the city. The watchmen moved their unusually long legs, gliding around the huddled bodies in chains, overseeing the sentenced on the roads to the derricks.

Until, from the shadows around the factories, a group of sleepless men emerged, enraged. They swarmed the procession, grabbing onto the watchmen’s long legs and trying to free the Enemies in chains. I pressed my back to a brick wall, amid the mob and the attempted escape.

My companion laughed with delight as a tall watchman stumbled and was overtaken. He fell to the cobblestones and was beaten until blood trickled along the stones. Somewhere, rifles began to fire in nearby streets, and someone sleepless threw books in the other direction.

“Will you help them?”

I shook my head.

“You could help them.”

I held up my soft uncalloused hands, which were worthless in such circumstances.

“Ah,” the dead man said, and I think understood my fear. And so we waited until the sounds of rifles and chains stopped and night evened out into regular city din.

The dead man sighed.

“You feel sympathy but cannot express it, have coin but cannot give it, have strength but cannot lend it. It is no wonder we are sleepless and deathless in this unnatural order,” he murmured. “Guilt is often the rot of failed virtue, you know.”

I could not meet his eyes, but I felt the truth in what he said.

ix.

Beside the acrid pyres of copper and iron, burning in broken stacks. Off the border paths and closer to the mirrors others advance. Between the tall and misshapen sentries who remember neither their Bodies nor their Minds. All of you, together. Too many for them to stop. Too many to stop, moving all at once that way.

vi.

Before we parted at the end of the evening, the dead man told me, finally, why he came. He clearly had a message to convey, and he thought it time to deliver it to me.

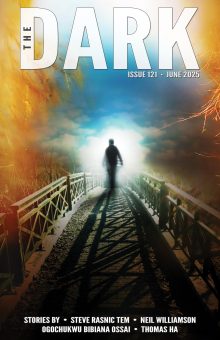

“If you remember nothing else of our conversation, remember this. Past the derricks and the executioners, there is a second place.”

“A second place?”

“A fortress, out there,” he said. “A fortress of mirrors, hidden, away from searching eyes. Those of us who are executed but do not die have seen that other place, past the gallow roads. It is difficult, but you can glimpse it on the windy plains. Something rising above a land so flat that it seems to go on into nothingness. And in that fortress reside the architects of this city and other cities, yes. If we all live in a kind of machine, that place is its engine, you understand. They who designate the laws, name the Enemies, and tax the city’s coin, they are the ones who lie there and sleep and dream entirely, deeply, surrounded by their mirrors, while you lie awake.”

I listened, and the body holding the head almost trembled, like it was speaking in its own way in support of the head, though I could not hear anything.

“The executioners guarding the plain are now more like empty metal than thinking men. Their instructions are degraded, so they do not know to attack the already headless. We remain unseen to them, as they remain unseen to us, and all becomes inverted the farther out you travel. So that the dead like us are free to cross between the cities without detection or obstruction.”

I listened still, more carefully, to the dead man’s words.

“The walls of the fortress are high. The weapons, impossibly destructive. The watchmen, bigger than the ones you’ve seen here in the city. But there are not so many sleepers in the fortress, very few left, in truth of fact. And they do not yet know about us, the executed, who do not die so easily anymore. They do not know how, with enough faith and resolution, we have learned to rise to our feet and pick up our heads. And enough of us, together, running for the fortress, can take it. And intend to take it. And we will take it, soon.”

I did not believe the dead man, but I wanted to believe him.

“My message is conscription. To you and to others. Because when it comes time to run the walls of the fortress, we will need everyone. And you will be among us, running the walls. You are not ready and free today. But when you are ready and free, I will see you at the walls.”

The dead man raised his severed head with both hands, and he gently kissed my cheek.

“I will see you at the walls.”

And then he left me to consider the plan.

viii

Find your way. Brothers, sisters, siblings. Left and right. Past the masked and robed ghosts who cannot hurt you anymore. Toward the shape. The spot on the land, reflecting the outer dark. We will go together. Together, all of us will go.

vii.

The sleepless years passed, and I soon forgot his words.

I could not rest or work or save, and, in time, like everyone, found myself imprisoned. I followed lines of people to the courthouse, where we were sentenced and declared Enemies. I followed lines of people in chains along the tall legs of the watchmen, out of the city and toward the derricks to that place where Enemies were sent.

It was only when we walked on the gallow roads toward the windy plain, that I thought again of the visitation by the dead man, all those years ago. The things he said about a fortress and its mirrors, barely glimpsed, somewhere between strange transparent figures that encircled me and the other men in chains. I looked out on an endless land and tried to see its shape through the wind and dust, blowing.

I remembered the years misspent in sleepless rot and felt a wellspring within my body, a violent and jagged sensation. I imagined, or maybe foresaw, visions of sleepers somewhere, dreaming deeply of delights, while we were left with the wasteland that reflected their careless decisions and designs. It felt like a wave of tumbling sand within me, only now reaching its crest but poised, eventually, to crash.

Instead I felt a rapid fall. A drop. I hit the ground and rolled and could no longer move in the darkness and dust.

Until soft uncalloused hands reached out gently and carried me up, and I heard someone strange, but familiar too, me. I did not yet understand, but I thought for the first time in forever of faith and resolution.

I listened and then finally remembered what we were meant to do.