What I saw and how I saw it: As if through a cracked piece of sea-glass, worn to kaleidoscope etching, all lights forming haloes and all darknesses eddying like some fungal sea. Through dry and bleeding eyes. At a distance, through the mind’s dirty windshield. In shreds and patches, drips and drabs, bits and snatches. By implication only, the same way Rorschach formed his blots.

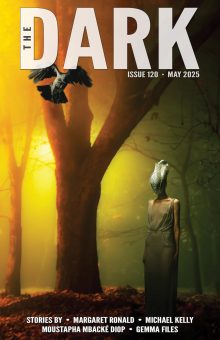

A woman cloaked in moth-wings so long they drag the dirt, standing on a high hill, overlooking us all—the town, the woods, the road, me. Every move of her shedding dust, tiny scales, reflective, musty. A scent like the very end of brush-fire, ash and ruin, a salted ground.

She looks down, she looks down, she looks down. Her eyes rake the ground. Her burning, burning eyes.

I will go insane.

I have gone insane.

It happened slowly, so slowly, up until it didn’t. I remember the creep and rot of it now, but at the time, I was distracted. So much to do. This is how women live, forever cocooned inside the lives of others, a fungal, many-layered shroud. It forms over years, ripping away only with the greatest difficulty, a scab atop five hundred interwoven scabs. Every rip you make spews spores, and those spores infect the exposed, raw flesh anew, sowing yet more layers—a whole harvest, spreading so fast, unwinding so slowly. As if I was an Egyptian already mummified, struggling to unwrap myself.

If men knew how often women are filled with white-hot rage when we cry, they would be staggered, I remember someone saying the other day, through the groaning static of my house’s ancient intercom system. We self-objectify and lose the ability to even recognize the physiological changes which indicate anger. Mainly, though, we get sick.

And oh, how true that is: We sicken, we are consumed, laughing wild amidst severest woe. We flourish with illnesses that have no cure and a thousand different names. Hysteria, the lung, wandering womb syndrome. Our own immune systems turn against us, fight us as if we ourselves were diseases, infestations. We wither, we swell, miscarry, grow phantom pregnancies, ingest our babies and turn them to stone. Our wounds fester, turn inside-out. Our equipment rusts and degenerates from over-use or lack of use or potential for use alike, decays within us, sliming blackly over the rest of our pulsing, stuttering interiors.

Things get lost inside us: Penises, forceps, scalpels. No maps to the interior. And every once in a while we simply flush our systems without adequate warning, drooling blood in clots from inconvenient areas, dropping squalling flesh-lumps everywhere—in trash-cans, in bathrooms, shoved under beds and swaddled in bloodied plastic, buried shallowly, immured behind walls that bulge with black mould-stains, pumping out flies.

This house I live in is sick as well—that’s no secret. When I first entered it, as a bride, I thought I felt it welcome me, but that was only an illusion; it fastened shut around me instead, less a mouth than a wound, forcing us to grow together in mutual disease. Where once this house began where I left off, we nowadays seem far too entangled for any such distinction, crammed tight alike with garbage and debris. A hundred thousand useless cheap and dusty objects lie enshrined within, packed tight from floor to rafters, and myself the most useless amongst them by far.

My husband orbits the wreckage on a weekly basis, returning only to demand his conjugal rights before returning to the office. I promised you children, he reminds me, less a vow than a threat, or a plea turned inside-out: Why marry in the first place, if not for some elusive dream of reproduction? It takes two, after all; we’re not amoebas, he and I, able to rip ourselves in half and call the result John or Jane Junior. It should be instinctual—birds, bees and fleas do it. Rats in the walls.

Just do it, darling. Just let it happen. Let me help you let it. Let nature . . . take its course.

I would if I could, I want to say, but don’t.

And thus I swell too, deflate, swell again, every month on month, with little real result. This morbid, moon-drunk cycle. Is it some infection inside me, roused and then soothed, stiffening like scar tissue? Some horrid tumorous intimation of cancer to come, temporarily defused every four weeks or so, but never fully cured? Hard to tell, without medical aid.

Impossible, nearly, ’til the evidence finally presents itself.

Later tonight she’ll come to me again, my moth-winged harbingeuse—perched darkly upright in the highest crook of a tree, standing rather than crouching. Fiercely predatory. Her gaze will sting as it passes me by, a cigarette’s glancing burn. Fragile grey snow will fall around her like ash from the sky, shake from her scales like pollen and dust, dissolving into the a wind that comes and goes in the same rhythm as her breath. She still smells of reckoning.

You are empty, she will tell me, lips unmoving. A living ghost, mirror-trapped, flesh-mired. I can barely see you, even from here, inside your mind. Can you see yourself?

Barely, I will reply.

I can help with that.

I’m unused to believing in dreams at this point, or even remembering them. My sleep is disordered, like everything else; I drug myself insensible, wake with head hammering and mouth dry. Opiates are like that. Sometimes I think I’ve poisoned myself so thoroughly that other people could probably drug themselves just by burning my body and inhaling the smoke.

The moth-winged woman has no eyebrows, just a doubled arch of eye-sockets as deep-set and high-ridged as an owl’s. Her hair is plaited thickly into two long braids, tied back with a sheaf of what looks like vines. Ivy-leaves crown her peering face, its features round and blank and pitted, skin nacreous-luminous as the hanging moon. Her nose-tip dips beneath her top lip, sharp enough to pike out a dead man’s eyes. And none of this will seem unlikely to me, as I register it; none of this will seem unfamiliar, or odd. It will seem, quite simply . . . inevitable.

What brought you here? I will ask her.

You did, she will reply, unsmiling, to which I will shake my head. Asking, as I do: Why me?

Because.

That’s no answer.

When she cocks her head to stare at me directly, at last, her gaze will hurt worse, yet so beautifully. Her mere attention enough to pin and mark me forever, an invisible brand.

The only one you’ll get, from me, she will say, then. The only one I have to give. Now . . .

. . . do you want it, or not?

Men’ll want to stick things up inside you, too, my mother used to tell me, in between spasms of vomiting that rarely brought up anything but bile tinged with blood. They just love doing that. Want you to love it, and say so, all the goddamn time. But you won’t.

Her voice, so tired and scratched all over, with all its bones showing: An x-ray plate from Stalinist Russia, printed under the counter with forbidden music. And what does the sound of it remind me most of, even now? Those words from the ducts, of course, eddying, static-laden. The intercom system, moaning blood-resonant, like sonar inside my skull.

Stick things inside, I repeated, in my unformed little voice. Like . . . their things, Momma?

Honey, that’s the absolute least of it.

My mother, I sometimes think—our mother—was made from cast-iron, for all her complaints; she pumped us out like etchings, the way a press works, spitting kids like a nail-gun does spikes of iron. Me and all the others, those grubs I hauled from pillar to post, wiping their tears and snot on anything handy. There were so many of us, you see, and the room we crammed inside when she had visitors was so very small.

They’re all outside and we’re all inside, that’s why, if you have to wonder. All of ’em hypnotized by that snake between their legs, that crawling worm—say we’re the ones got the whole human race cast out of Eden just to gnaw a piece of fruit, but is that true? How can it be? They’re the ones speak serpent, baby, not us; remember that, if nothing else. That’s the root of the trouble, right there.

Repeating again, dumbfounded, as if chewing the words over twice would make them more palatable, let alone understandable: They have no insides?

Ha, and isn’t that the truth; none that matter, anyhow. Now get in the closet and be quiet, the lot of you. Keep your mouths shut so the nice gentlemen don’t hear, or there won’t be any supper.

Red light on the wall, flickering gently, and the smell of gas besides. Red curls on the wallpaper, raised mock-velvet mouths all screaming soundless, gums bare, with never a tooth between them.

I remember pressing my hand to my sister’s lips—sister? Brother? Baby?—and holding it there firmly, no matter how hard they tried to bite, as we watched my mother entertain through the ill-set crack between door and jamb, the keyhole winking at us like her phantom third eye: Stay still, stay silent. Study what happens now, if you can stand to.

And then the usual choreography, the flapping buttocks, the flailing limbs. A music-less dance, done badly. That same flabby pink worm-snake she’d been raving over earlier crawling out of one set of drawers, excruciatingly slow, just to burrow deep again through the barely-tied strings or too-wide, dirty lace-festooned leg-hole of another.

It was here, through this narrow strait-gate, that I got my first glimpses of the future, without even a cracked sea-glass lens to scry them through. How my life would be nothing but a series of ins and outs, in and between all the rest. How this closet I squatted in would prove, if only metaphorically, both tomb and womb.

Where did they all go, I sometimes wonder, these relations of mine? My fellow spawn? Out into the world like shrikes and jays, screaming, spreading carrion. Riding the migratory urge like another air-current, one I must have been born unable to interpret, and leaving me behind.

This house is a cage, I think. Like this world, or my body.

Yes, the intercom replies.

I am buried here, rotten, rotting still. I always have been.

Yes.

But—more and more—I do not think I always must be.

As evening falls, like clockwork, my husband comes home, seeking his weekly solace. He expects dinner served promptly, followed by me spreading myself out overtop clean, fresh sheets, all shaved and powered and sweet-smelling. But tonight is not that sort of night.

Are you here? He calls out, through the darkened house. Honey, where are you? What happened to the lights?

(I went around crushing them in an oven-mitted fist, dear. The glass rained down like stars, and in its tinkle I heard the moth-winged woman’s laugh.)

My husband moves further inside, feeling for the switches, muttering strings of swear-words each time he flicks yet another one that also fails to work. Then raises his voice once more, calling: Honey, it’s me—can you just answer me, please? What’s this stuff all over the floor? What’s that smell?

(Dinner, dear. What else could it be?)

He’s entering the kitchen now, its air thick with smoke, equal parts charred chicken and melted plastic. Slipping on defrosted vegetables that squish beneath his shoes, I hear him hit hard as he lands on one knee, one hand, skinning both against the floor; he must surely be feeling his raw flesh burn as it connects with a scattered layer of salt mixed with bleach that I’ve spread all over, at this point, since he gives such a ridiculous little yelp of pain before screaming my name. Damn it, Ayla! What is this? Where the hell are you?

(Upstairs, dear. Follow the sound.)

(Follow the sound of her wings.)

Granted, it’s currently smothered beneath the carefully overloaded washing-machine’s grind and churn, the steady sloshing of water as it spills down the staircase, rendering the deep-pile carpet sodden enough to squish beneath him as he wades upwards, pulling himself along by the bannister. But the further he travels, I trust, the more audible it will become.

Turns out, I have things inside me already, I want to tell him, and they need to show themselves. They need to talk to you, my love.

But really, why spoil the surprise?

Up, and up, and up. Past the ruin of the bathroom, the tangle of the walk-in closet. Through the corridor of photos, once perfectly posed and framed in gold, all left hanging askew and smeared with filth, their individual panes of glass carefully shattered. Into the master bedroom, where every sheet lies slashed and the mattress excavated fistful by fistful, eiderdown swirling like a snow-flurry hurricane tangle. He breathes some in and coughs before doubling up, coughing even harder, as the moth-winged woman’s pheremonal danger-stink finally begins to penetrate. Sucks yet more detritus down and spasms, hands to mouth, while he spatters his palms first with blood-tinged mucus, then thin, bile-flavoured vomit.

He calls my name again, a growling moan, but I . . . I don’t answer. I have no reason to.

I simply press my back against the balcony railing outside, looking up into the black, black sky, and wait for him to find me.

White-hot rage.

I remember reading about a woman running naked down a road, both arms severed just below the elbows and ground into mud to keep her from bleeding out; I remember how three cars passed her by before one stopped at last, that one driven by a couple on their honeymoon. I remember reading about a man who testified that the first time he strangled a woman to death during sex, they were both so drunk he didn’t know what he was doing, and she didn’t try to stop him. I remember thinking how much more persuasive that testimony would be, if only we could summon her to rebut it.

I remember my first abortion, looking up over the rubber sheet and the doctor’s bent head to fixate on a framed 1940s-era poster on the office’s back wall; Meat is a material of war, it read; use it wisely. I remember my third miscarriage, listening to my body mourn even as my mind flooded with relief, knowing that whatever lurks inside me should never be given a chance to escape. I remember driving two states over to beg another doctor to tie my tubes, only to hear her argue I might reconsider and return to sue her. And: No no, you don’t understand, I remember choking, through nauseated tears. The ways I’ll change, if something does manage to take hold . . . the things that thing will do, if it survives . . .

I’m not hysterical, for God’s sake; I never have been. I simply know myself, intimately, well enough to understand that no one else should ever have to. To know that all my bloodline truly prepares me to spread, even when admixed with someone else’s, is disease, and rust, and blight.

Ruin, sister. Reckoning.

Yes, oh yes. Exactly right.

Above me, the moth-winged woman hovers stable as a dragonfly, flickering with promise, baptizing me in dust and ash. My harbinger angel, poison-soaked and -haloes, with every sharp-spread finger and toe finally recognizable—at such close quarters—as less a claw than a sting.

Inside, my husband still stumbles back and forth, searching, calling. Her eyes burn and mine meet them, itching to catch fire fully; I feel cataracts form like half-dollar sized mirrors, ferryman’s fare, reflecting everything. They make my pain and rage look beautiful. Almost as beautiful as her . . .

But not quite. Not quite yet.

I’m not sure about this anymore, I tell her, silently, hearing the intercoms wheeze to the pulse of my thoughts. It doesn’t seem fair—to him, I mean.

You called, she reminds me, her voice leaking from that same system, cloaked in static. Your choice, not mine. All of this is your choice, Ayla.

I know, I reply. Never think I’m not grateful. I’ve been alone so long, suffering, and it’s not as if he noticed. But still . . . ignorance shies close to innocence, especially here. Whatever he did to me, I let him do, without question. Should a man whose only crime was to think he loved me really have to die, just because I don’t want him? Because he never guessed I never did?

Should he?

. . . maybe not.

A click beneath my breastbone, turning. It’s as though I plunged a key made from knives inside myself, cutting myself one last hole, through which I can finally hope to escape my body’s cumbersome flesh cage. And I feel myself swell, feel myself harden, feel myself breathe out until my lungs deflate, a crushed white butterfly. Feel my bones turn to brass, my skin to scales. Feel my hair uplift itself to taste the night air like a corona of snakes, even as my back humps and my shoulder-blades crack apart, exposing my spine. Making room for this fragile new set of wings now poking itself out from underneath, mainly nerves as yet but already widening, thinning, stretching to form a pair of membranes stiff with bioluminescent cartilege that snap and spit against the night. I open like a flower, tasting my own destruction, turning myself inside-out—and even as I gasp with the sheer beauty of it all, as I howl with elation, I watch my husband’s head swivel my way at last: There she is, there.

Watch him lunge for the french doors that separate balcony from bedroom, even as I thrust my hands up to meet the moth-winger woman’s and beg her to lift me up, to take me away, to gather me in and fly. I want to be gone now, long gone, before he has the chance to recognize me. Before he has the chance to try and stop what can’t be stopped.

He can’t, she assures me, all ten sting-fingers plunging deep into the webs between my own blunt digits. None of them ever could.

I know, sister.

I’d kill them, if they tried.

I know.

Ayla! He screams, as her own wings given one tremendous beat, powering us up beyond the clouds. I don’t bother to answer, though.

That is no longer my name.

What I see, and how I see it: The ground, swooping away as she swoops yet higher, higher, higher. My husband staring after, reduced in one beat more to pixels, to memory, the absence of such. The house, a tiny, infinitely crushable toy, no longer worth the stepping on. This stupid human sphere of reproductive torque and lurking mortality, in which—from now on—I will share no further part.

You can’t just think yourself out of things, my mother used to tell me, not even if you go crazy. More’s the damn pity. And that certainly proved true, for her; far too bitter-proud to pray in her personal abandon, so no angel ever came to liberate her from that penitential whorehouse rack she’d condemned herself to . . . along with me, of course, and all my siblings. Those hate-cured seeds she cast back into the maelstrom after fertilizing us with the disgusting spectacle of her doom, hoping our well-learned capacity to turn pleasure into plague might raise a crop to envenomate the world that ruined her.

I am my own child now, I think, looking up at the moth-winged woman and knowing her for what she is: Yet another maggot bred from my mother’s corpse come at last to glorious fruition, buzzing through the cosmos, sowing decay and wisdom in her wake. And I hug her close, secure in this vision; I grow myself into her, tucking my nakedness into some pouch-womb birthed from imagination alone, where I can sleep for as long as it takes to dream myself back into being. I cicatrice over, forming my cocoon, looking forward to becoming, to being. To playing harbinger myself once I emerge, once we descend again on an unsuspecting planet full of of things like me.

Don’t drop me, I beg her, curling close.

Never, she replies.

Originally published in Hymns of Abomination, edited by Justin A. Burnett.