Trauma is a ghost that haunts you. Grief another.

Dad was dead. Mom gripped in a pall of anguish. And Sophie wouldn’t shut up.

“Ophelia,” Sophie was saying, “we all perish in the end. Sometimes our end comes sooner than we’d like.”

I stared at her. It was night. We were on the backyard patio. Candles on the table pushing back against the intruding darkness.

“Maybe he really is in a better place,” Sophie said.

“Fuck you.” I folded my arms tight across my chest, looked down. “It’s not like he was ill, Soph. He was taken.” There was no proof of that. That’s what I chose to believe. He was just gone one day. Missing. Until they found him. Part of him.

“‘For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come.’”

I looked up. A strange smirk stretched pumpkin-like across Sophie’s face. “C’mon,” she said. “You should know that one.” A sigh. “It’s just projection, Ophelia. This thing you found in the cave. It’s not our dear dead Dad. Have you heard of Apophenia?”

Always smarter than me. “No.”

“It’s connecting something to another thing when there truly is no relation. Random coincidence. You just don’t want to believe Dad is really gone. He is. Trust me.”

I’d found a cave. There was something in the cave. A body, perhaps. Dad, perhaps. His embodiment, anyway. Sophie had scoffed at the idea.

“They found his remains, Ophelia. He’s not missing anymore.”

Technically, they still haven’t found his body. Just his head.

“What is it then?” I asked. “What could it be?”

The candle flames guttered and Sophie’s face flickered orange and black. “Hmm.”

Sophie loved making up stories. Loved scaring me.

“Fifi,” she said—and she only said my nickname when she was trying to wind me up, to scare me, to get my attention—“imagine this area hundreds of years ago. Before the parched land and contaminated creeks. Inhabited by the Cree. They fished the waters. Cultivated the land. And they found those caves. They didn’t live in them—they’d already settled—but they mined them for quartz and other stone to make tools. And they were spiritual places to the Cree.”

I looked up. Ancient stars glinted in the dark. The crescent moon cut a sharp grin against the fabric of the night.

Sophie continued: “A Cree elder had sons. Twins.” And she smiled sharp and wicked like that moon. “He favored one over the other,” she said. “One was good, he imagined. The other evil.” She winked. “A tired trope, Fifi, I know. But stay with me. One twin was constructive. One was destructive.” Sophie paused, features serious. “Which are we, Fifi? Maybe we’re both. Maybe we’re the same.”

“I’m not like you.”

“The Elder disavowed the one son,” Sophie said, “and sent him to live in the cave. Each day he would send the other son to the dark cave with a meager food offering. Half a cob of corn. A few bits of rabbit. A tiny scrap of whitefish. Unbeknownst to the Elder, the twins would swap places so that on alternate days the disowned son would come back from the cave, smiling and sweet. This went on for weeks and the Elder was none the wiser.”

Sophie grew pensive. “Imagine not knowing your own child, Fifi.” She sighed. “But the Elder was poisoning the food. He meant to poison the ‘evil’ twin but was slowly poisoning them both. They took ill. And one morning the Elder found his son dead. Instead of grief, a great rage consumed him. How could his favored be dead? Why couldn’t it be the other? So he carried the lifeless body of his son to the cave, vengeance on his mind, and found that the other son was also dead. Only then did he realize his mistake. His rage grew. Conspirators both! And he bound them together, made them one, and left them in the mouth of the cave.”

A sudden wind pulled at me and I shuddered. “That’s not what’s in the cave,” I said.

Sophie just grinned.

Trauma is a ghost that haunts you. Grief another. Terrible twins. One will grow to eat the other.

That’s what the thing in the cave told me.

I wrote it down when I got home from leaving the offering to the thing in the cave in the hills beyond the foul creek behind our suburban house. The pale moon and my cellphone’s flashlight guided me down the hillside through the wild bracken and across the slippery moss-coated rocks protruding turtle-like from the black, sluggish water. Quickly over the back fence then around to the front. Extinguishing the light from my cellphone, easing the key into the recently oiled lock, then crossing the dark foyer and padding lightly up the stairs, trying not to wake Sophie—Mom already numbed asleep—to my silent room where I opened a Word document on the laptop and typed it out.

One will grow to eat the other. What did it mean?

The thing in the cave was a scarecrow. That’s what Sophie said when I showed it to her the day before I secretly left the offering. And it did resemble a scarecrow. It was like a large cross or a canted X, made of wood or bone—I wasn’t sure which—with muscly, twining sinews, and a nubby growth at the top like a malformed Jack-O-Lantern. Some sort of old sculpture, perhaps. Ancient, maybe. When I put Dad’s old denim shirt on it, the offering, I briefly touched the thing and it felt like everything and nothing, smooth and rough, warm and cold, alive and dead.

I don’t know why it wanted the shirt. But Dad was never coming back, and Mom hadn’t cleaned out his closet, so I obliged. It was difficult to place the shirt on the thing’s tilting frame, so I draped it over the strange lump, its ‘head,’ like a cowl. It hadn’t said it was an ‘offering,’ but it felt like one. And it hadn’t specifically asked for the shirt. Bring me something of his, it’d commanded. Dad was always wearing that shirt—the denim faded bone-white like a sky leeched of all its blue—unbuttoned with a tattered band T-shirt underneath. That’s how I picture him still. It was like having him back.

“A scarecrow is all,” Sophie said that day. But scarecrows don’t talk. And this thing did. I didn’t tell her it was speaking to me. I told her it most definitely was not a scarecrow. “What would be the point of putting a scarecrow in a cave?”

“To scare things away,” Sophie said, smug. Sophie was 486 seconds older than me. Older and wiser.

“Things?” I asked.

“Animals,” she said. “People. Us, probably.”

“Us?”

And then she started in on one of her stories. That 8-minute age gap felt like 8-years, to me.

Sophie held her phone under her chin, flashlight on. Her face was a hooded corona, her eye sockets and mouth deep dark holes.

I shivered.

“Fifi,” she said, “do you remember that girl, Jenny, who disappeared from school last year mid-term and never came back?”

“The one who moved?”

“Uh-uh,” Sophie said, her dark mouth grim. “Didn’t move away. She died. Was killed, actually. Murdered.”

I laughed, but it wasn’t a pleasant sound. “Another of your fictions, Soph.”

Her voice grew quieter. “Everyone just assumes she moved. Kids suddenly vanish and we don’t think anything of it. We don’t question it.”

“What other explanation is there?”

“Shhh,” Sophie said. “Not so loud. He’ll hear.” Her voice was odd, echoey, as if coming from somewhere else in the cave.

I glanced at the thing. “Who will?”

“The killer,” she whispered. Sophie leaned toward me, the phone still lighting her face in half shadow.

A scuttling, scraping sound. Something moving. She was pulling out all the stops. “Cut it out,” I said.

“We’ll get to that part.” She paused. I heard another faint noise. Sophie cocked her head. “I heard this from a kid who knows Jenny parents,” she said. “Jenny was over in the next county, riding her bike down those red dirt roads, going to meet some guy. This guy, Dale, says Jenny never showed.

“Dale lived in this big old house with his big old man, with nothing but crows and cornfields as neighbors. Jenny’s Dad found Facebook messages to Dale and went out to the house alone one night. He found a shed of bones, Ophelia. Human bones. Femurs, tibias. And skulls. A whole shed of skulls.”

Daylight was disappearing, and the cave grew dimmer. Sophie’s flashlight was dimming, too, that grin darkening.

“Jenny’s Dad kills them both, Ophelia—Dale and his old man. What else could he do? They both had to be in on it. He found a big, hooked knife in the shed, went into the dark house and gutted them both while they slept. Ripped them wide open.”

“Sickle,” I said.

“Whu—?”

“The big knife. The hook. It’s called a sickle. Or a scythe.” For once I felt smarter than Sophie.

“That’s not the point,” she said. “Jenny’s Dad drags the bodies to the corn field behind the house. Tears out their intestines. Stuffs straw and dried corn husks into the bloody cavities. Makes crosses out of old fence planks. Nails them to the crosses and plants them in the field.”

“I—um, that’s ridiculous. I would have heard about it.”

“Nah,” Sophie said. “Took ages to find them. The house was big. The stalks high. Cops did a ‘wellness’ check when Dale went missing. Found them in the field. Crows had got to them. Ironic. Wasn’t much left. Cops somehow traced Dale to Jenny, which lead to her dad, via tire treads, mud, what have you.”

“It would have been on the news, my socials.”

A small chuckle from Sophie. “Cops and media are in on it. Sheesh, Ophelia, you know you can’t trust either. A. C. A. B.”

“In on what?”

“Cover up,” she said. “Turns out Dale and Pops took a kid every autumn at harvest time. Some sort of bounty to ensure abundant crops every year. There was that kid, Mark, year before last. Moved away.”

In the near-dark I sensed Sophie smirking. “Good one,” I said, a slight tremor to my voice.

A soft wheeze, then a scratching sound.

“You can stop now, Soph.”

“I’m not doing anything,” she said.

I sighed. “Okay.” Then, “You said the killer might hear us. But he’s dead now, right?”

“Oh, there’s always another killer,” Sophie said. “That’s how it works. Do you want to know what happens next?”

My voice was whisper soft. “Sure?”

“This.”

And she turned out the light, leaving me in the dark with the dad-thing. I sensed it there in the quiet and the dark. Waiting.

I supposed it was better than not having any dad. Trauma is a ghost that haunts you, it’d said. Grief another. Like something Dad would have said. It was a smart dad-thing.

I knew all about trauma and grief now. Mom, too. Sophie acted as if nothing had happened. Mom said that’s how Sophie deals with things. Ignores them. I knew better. She just didn’t care about anything. Not Mom, not me. Certainly not about Dad. She only cared about herself. And her stories.

The world is full of smiling monsters.

I wrote that one down, too. I wrote them all down. It’s true, I thought. A smile is disarming. Here’s someone who is happy, it says. Someone you can trust. A smile is like that sickle, curved and cutting. It can decapitate you.

When we first moved to this house, with our own rooms, before I found the thing in the cave, and before the creek completely smelled of ammonia or sulfur, before it choked and moved like cold molasses, Sophie and I would follow it home from school. We’d watch the tiny brown fish darting, and race twigs or bottlecaps in the faster moving areas. In the lazy summer silence of the ravine, we’d whittle branches into pointy killing sticks with one of Dad’s penknives. Hunt for frogs with those very sticks—stabbing them in the back and pinning them to the ground to flail and spasm in the hot sun.

One such day, on the muddy bank of the creek, we found a two-headed turtle, languid and still in the early summer heat. Sophie put aside her pocketknife and the stick she was whittling, plucked the turtle up, nestled it into her palm. The tiny heads cast about, eyes searching, mouths opening, closing.

“Imagine,” Sophie said, holding the tiny turtle up to me, “this could have been us.”

I sensed one of her stories coming.

“Two-headed twins,” she said.

“That would never happen,” I said.

“You’re probably right,” she said. “We’re lucky. We both made it out. One of us didn’t die.”

“Made it out?”

Sophie smirked. “The womb, silly girl. We made it out of the womb. Not all twins do. Sometimes … there’s the vanishing twin. Here today, gone tomorrow. Turns out one twin simply absorbs the other. Kills it.”

“Why?”

Sophie flashed her monstrous smile. “It’s what we always do in the end, isn’t it?”

She stroked each of the tiny turtle heads in turn, her face placid, a faraway look in her eyes as if daydreaming. “There once lived a two-headed girl. Girls, I should say, as each was an individual. They just shared a body. They had a doting, loving mother. ‘Two heads are better than one,’ she’d say. But the father refused to accept it. Being a father doesn’t automatically make you a good person, does it, Ophelia? The girls are loving, attentive, content and happy and considerate. Everything a parent dreams of. Perfect. Except for the one thing. Two, actually. Their shared heads. The father is ashamed. Takes them to all the doctors and specialists. There’s nothing to be done. The girls are healthy and vibrant and intelligent. Beautiful. But the father can’t see their beauty. They are an abomination. A cruelty inflicted upon him.” Sophie glances at the fidgeting turtle, looks back to me. “There’s nothing quite so fragile and frightening as the male ego, is there?

“One scorching day while their mother is at work, the father bundles the girls into his pick-up. ‘A picnic,’ he says, whiskey on his breath. ‘Just us!’ A fever in his eyes. He drives far out into the country, along roads of hard-packed dirt that hadn’t seen rain or even another vehicle in many a month. The girls look this way and that, puzzling about their surroundings. Worry etches their faces. A knot grows in their stomach. In the bed of the truck, under a tarp, is a bone-saw. A shovel. And, if needed, an axe. He’s a mad surgeon.

“Down another dirt road wedged in by tall pines, then onto a tiny tract barely wide enough for the truck, and into a small clearing. The girls are beyond worried. They grab for the doorhandle, but their father pulls them from the truck, drags them to the back, unlatches the gate and reaches under the tarp for the bone-saw.”

Sophie’s hand is wrapped around the turtle’s body. It’s just two searching heads, sensing, assessing for threats.

“And,” I say, not able to help myself, “what happens next?”

“Much later that day the girls were found limping down a country road, dishevelled and dirty. There was blood on their clothes. They said they were out walking, got lost, cut themselves on brambles and thorns. And later still, when their father never returned from work, calls were made. He hadn’t shown for work. No one had seen him. And no one ever saw him again.”

Sophie placed the turtle down. It slowly inched toward the water. She picked up her knife, eyed the blade. “You see, Fifi, they never checked the blood on the girls’ clothes. It wasn’t their blood. Their will to survive was stronger than their father. Just another weak man.” She watched the turtle, creeping forward. “Would it have worked?” She reached for the small creature, flipped it over. It’s arms and legs floundered in the stagnant soup of the summer air. “I wonder,” she said, as she rested the knife-edge on one exposed neck. “Would it change anything?”

With the knife pressed to the turtle’s neck, Sophie waited. The turtle stilled, as if playing dead. The heat was so thick it seemed even the world waited. But I didn’t. I got up and left.

I knew it wouldn’t change a thing.

Sophie’s text read: Meet me at the cave. 8pm.

And that’s where I found her, inside the darkening cave mouth, as the early autumn pumpkin-sun dripped beyond the far horizon like a runny watercolor.

She stood beside the dad-twin-thing, a backpack at her feet, phone in hand, its glow the only light in the cave. “My dear, Fifi. My dear, Ophelia. What dreams may come.”

Sophie looked up at the thing—the light from her phone illuminating a small, sardonic smile on her face. She lifted a corner of the shirt, let it drop, then looked back to me. “What a lovely, personal touch.” Her voice as cold as her dead-penny eyes.

Sophie turned her phone screen toward me. “I found something of yours’. Your little writings.”

She’d been in my room, then. “Stole, you mean.”

“He always liked you more.” She squinted at her phone. “Such wisdoms, Ophelia. ‘Trauma is a ghost that haunts you.’ Truly profound. And this one. ‘We enter this world with nothing, and so leave it with nothing.’ Brilliant.” Sophie smiled. “This one is classic. ‘The world is full of smiling monsters.’” Her own smile widened. Her finger scrolled along the screen. “But my favorite—‘One will grow to eat the other.’ Truly apt.”

“What of it?” I said. “What do you want? Why did you ask me here?”

“This is the next part of our story, Fifi. Don’t you want to know what happens next?”

“No.”

Sophie bent, unzipped the backpack, pulled something out. It briefly glinted in the glow of her phone. Dimly, I could just make out its long curve.

“Fifi?”

“What?”

“Are you afraid of the dark?”

“No.”

“You should be.” She dropped the phone.

The world went dark. Movement, as if a shuffling forward. And I sensed it there in the sudden gloom. Waiting.

The offering fit neatly in the backpack. I’d have to figure out what to do with the rest. The sickle would help.

And now? Now I wait. I wait for it to speak to me. I wait for it to tell me what to do.

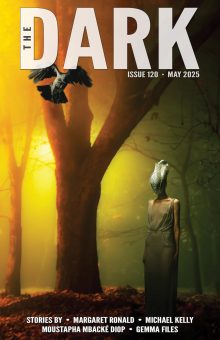

Originally published in Nightmare Abbey, Issue 7, November 2024.