7 centimeters

of my ring finger on my right hand. Sliced with a hot knife through gristle and tendon and bone, as though it were as soft as an ingot of butter.

2490 kiloliters

of water had once ripped her and I from one another, had once sheathed her and I to one another.

In the middle of it all was a jungle. And in the middle of the jungle was a gash of concrete within the forested darkness. This concrete semi-circled into a squat array of buildings, into the Erode Christian College of Arts and Science for Women—a missionary endeavor of the Church of Scotland to wring South Indian women into the narrow flute of Bible truths. But like most missionary undertakings in Tamil Nadu, this too snarled into indifference as the locals flinched away foreign ideals and foreign encroachments as they were wont to do.

Over the years, our college had become a knot of expendable girls, offering subjects like Homeopathy and X-ray Crystallography and Folk Practices that sounded carefree and bohemian on paper, but were simply designed to fill the listless expanse of day that sludged from one hour to the next. Majors like Engineering or Accounting or English Literature were deemed unnecessary with their meteor-bright promises of ambition and status, a hindrance for the young women that were expected to anvil themselves with a degree just for marriage.

The only breath of tenacity on our campus was a euphorbia shrub that knuckled against the windows of our hostel dormitories, the greenwhite glint of its leaves a sieve of light through the glass, freckling our faces with shadows from its creamy flowers that parted the foliage like teeth.

No one cared about anything, at all.

Phrases like proper decorum, moral turpitude, no loafing, and academics over hooliganism, fluttered out of staff lounges and plunged to their doom in the underbrush. Most of us attended college strobing on coffee and a mash of pills from the town pharmacy—an opiate confection better suited to lorry drivers who drove fifteen-plus hours across state lines without stopping to eat or piss. In class, we sat immobile under a drug-rimmed void, our attention fractaling into shards with pleasantly blank expressions on our faces. And as long as we were tactful in bribing the hostel wardens with arrack at regular intervals, we could slip in and out of campus unnoticed.

Some of the girls fell into the toil of boyfriends and married lovers from neighboring towns and villages. Mediocre sex and controlling men were the only flashes of revelry around these parts, so the students braved the risk-calculus of defying college administrators. These men were all the same to me—an amorphous, shifting-eyed clump whose collective entitlement roped around my neck and under my armpits, leaving friction burns in its wake. Besides, my parents had arranged my betrothal to a distant cousin I did not know, bottle-corking my life into clean submission.

This is why I chose the forest instead. Why I chose to impale myself on the dense groundcover of the lantana, choking on its powdery blooms as it stripped the skin clean off my calves in sheets. Why in another instance, I stumbled over an anthill, my thighs already scudding with bites. Later, I would core each scratch and bruise with my fingers, until my welts pulped into tenderness. I wondered if this was what it meant to feel something—blood, its crusted-over aftermath. Somewhere else, a distant promise of pain.

Once, as I pushed further, still further into the forest viscid with heat, I came upon a crumbling stepwell a few kilometers into the woods. Such reservoirs were not uncommon around these parts: bodies of water sluiced out of the earth and into pipes through boreholes. My nightly excursions now haloed with purpose, and I began swimming in the well’s cool depths under the foliaged dark.

That night started without incident.

I peeled off my kurta and pants and as if on cue, silken-winged chironomids hummed over my bare skin as I stepped closer to the water. A repetitive sound nailed me in place amid the shadowed reeds, a low splish-splash that felt like it belonged to a large animal body. The enzyme-burn of my fear pulled that moment through an eye needle—a breath, an immobile form, a tongue lapping against the steps. I wanted to scream. I wanted to fling myself into the well and throttle whatever it was.

But a spherical face pushed out of the ripples, followed by a gulped exhalation, a nose ring concentric-circling her neck, and my anger settled into recognition.

It was our Folk Arts professor. Shrouding herself in voluminous cotton saris, she would move from class to class during the day as though she were insubstantial—a wisp, earthed by the gold Nath through her left nostril.

Her hair was a braid of feathery milfoils across the well’s surface. Arms softened into silhouette as she cleaved through the water. I continued to watch her, an improbable want knifing into me.

And then a glottal elapid mouth, fangs, liquid spuming up my nostrils.

Vacuumed into a black so thick and opaque, I felt comforted that this was how it all ended—stricken by desire, suffocation, and the well I so loved.

43 inches

of snake shed was the only part of her that I had found intact, crimped within a groove on the stepwell after she was gone.

But that was not entirely true. She had also left me a story about a prince.

இப்போ கெழு, she would say in Tamil, after I had spent an afternoon in her office, rumpled between her thighs underneath an overlarge desk, my wrists spider-silk bound, my head cowled by the lower half of her sari, and I would always bite my laughs into her while she sat there as though hewn from gneissic rock—forcefully dull in a way that put a finite end to conversations or questions, the upper half of her sari pleating across her left shoulder, a double-lined teakwood panel the only furrow between my unclothed body and the students’ feet, the wide-open gorge of her face still immobile as she welcomed or bade her students goodbye, as she came undone suddenly, always suddenly, a rip-current in the back of my throat as I held her constriction, her pleasure, in my mouth.

Listen now.

இப்போ கெழு, she would say in Tamil, after the waters of our dissolution, a world or two or three in my stomach. She said that she was from the sea. That she beached herself on the shore between her love and his love, the lacquered sheen of her ventral scales cupping darkness, a sine wave granulating into dust.

Who was he? I would ask.

He was always different, she would say, pulling me into the upside-down night of the stepwell, pale green azolla and velvetleaf drifting in clouds past my ears as she dragged me still deeper, my lungs swelling out of my ribs, a plural-sac inflatable devoid of air, and I thought to myself, this is happening again, letting desire fishhook me into compliance. The sky at the floor of the well was spongy and perforated like an earlobe, leaking red. She would stream apart in hexagonal scales of blue and black, her once-human skin crackling open around her once-human mouth. Then a ripple and a lateral expansion, her lidless eyes refracting the moonlight as it washed our tongues. I wasn’t sure if I was alive or dead or a half-life suspension in formaldehyde. What did it matter when the pale cream of her dorsal body furled around me as her blue-lipped mouth kissed neurotoxin promises down my torso? What did it matter?

Listen now.

In each of her stories that were mostly the same, the endings sometimes varied.

Every time, she would speak of the prince whose beauty was as fierce and unyielding as a thunderclap. His father was the Lord of Flowing Rivers and War after all, and his brothers were in order: the son of the Lord of Shadows and Judgement, the son of the Winds, and the twin sons of the Horse Physicians. They had one wife among them.

Everybody knows this story, I would say.

Not like this, she would reply. Let me tell you about their wife.

This princess was an ayonija—a woman who had not been gestated in a womb. Her father was the Lord of Fire who was also her mother, as she had leaped out fully-formed from the flame instead. But this was not the princess’ story, not quite.

This is just to make you understand that being a husband of the woman who was a child of fire was not easy, she had said.

Why does this feel like an excuse?

Just listen.

The prince who was the son of Flowing Rivers and War was fond of carnage. He never had to travel far, as battles landed on him like felled trees wherever he went. But even princes fond of fighting eddied into currents of exhaustion, and he found himself on a riverbank, missing his wife.

Who is to say how it happened? Perhaps he saw the snake first, sunning its honeyed underbelly on a rock, opalescent scales dripping golden light. Perhaps the snake saw him first, losing herself to his storm-cloud skin and eyes and glistening forearms.

In one version of the tale, he would have a son with the snake. In another, he would become a father to many children, lulled into comfort sans princely responsibilities. In yet another version, they met on the seashore instead of a riverbank, a cresting inevitability, their union already foreordained. But in every story he would leave the snake, his son, and his children behind. He would always return to his brothers, his wife of fire. He was a prince after all.

I won’t leave you, I would promise each time.

You are not a prince, she would laugh.

37 feet

of a washed concrete stage floor, across which you pushed a wooden table. Do you remember their faces? Enthusiastic, fidgety, offended. I remember it all. It was the Annual Day Function where college administrators, local politicians, MLAs, sump pump entrepreneurs and housewives roused themselves from their bridge games and vendhuthals involving mortifications of the flesh; making their presence known on campus since an event was an event after all, even if the free snacks were khara biscuits and coffee veined with bluish milk. That day reminded us that our college sometimes grasped at normalcy, that it did have clubs. I mean, did you know that there was a club claiming to promote Eastern and Western solidarity through fusion dance? Their members popped and locked to Tamil kuthu songs on stage, and as I watched them, my embarrassment puddled into something else, a thrum along the edge of my hairline. Something new, like awe. None of us knew how to join these clubs that stood outside time. I asked you once as we lay on the widest step of the well, our legs scissored under a threadlike balsamic moon that reeled light back into itself, and you wouldn’t give me a clear answer. It was okay. You were preoccupied, terror and passion congealing your words a whole six months before the Annual Day Function because you were expected to put up a solo performance. You were the Folk Arts Professor after all. But could you blame us for anticipating a show that was at least straightforward, like a kavadi where dancers weighed themselves down with a parabola of wood held in place by a rod across their shoulders, arcing and bowing their obeisance at the foot of a papier-mâché approximation of our six-headed god of war adorned with peacock feathers? Or even a villu paatu, a chanted intonation, a lament, involving a tightly strung bow as an instrument? So when the lights dimmed and we all hushed in excitement, we could not help but respond in surprise at the single table that decorated the stage. I admit, I was so fixated on you that I didn’t see the table at all, at first. You had walked out in only a petticoat and nothing else. I recognized it immediately, as I was the one who had dyed it with turmeric—a beige, whorled in yellows—for you. I felt marked, chosen somehow. A nudge in our arrangement, your feelings a pulse away from indifference, a not-quite, but also not a no, inching into a terrain of acknowledgement where I could allow myself a nub of hope. Gasps ricocheted across the audience. You were fully clothed, but a petticoat was an inner garment, the first of many layers closest to the body, its visibility an affront. You knew and you did not care because you were already cloaked in a flesh and blood skin not your own, the petticoat your fourth or fifth or sixth membrane, and that was when I think my desire signal-flared into love, a pyrotechnic explosion, all-consuming. You had now begun to dance, each movement towards the table a practiced bharatanatyam nadai, step by excruciating step. Your eye-contact with the audience was a taut line. Not a sound was heard. Then you slowly slid the table from one end of the stage to another with your elbows. Then you sat on the stage floor with your back against its legs, your hands crossed in a shunya mudra—the gesture for emptiness, for what seemed like a whole hour, but perhaps it only lasted a few minutes. In the front row, a politician cursed his sycophants, his voice a conspicuous javelin of sound, rising and rising as if to warn. His white veshti and shirt blazed with purpose in the darkened auditorium, and we all understood who the expletives were actually for. As if on cue, parents walked out in pairs as our college principal placated them with fee vouchers and lunches. Some of the more rowdy girls hooted ei and yakka and threw paper planes at you. One plane skimmed the stage floor in a low axis, grazing your feet. You did not move. But here’s the thing, I couldn’t understand why they didn’t see what I saw, which was your tail splintering halogen beams into chips of light, your mudras a dehiscence through your human-seeming limbs, your underbelly möbius-looping the perimeter of the stage. Why could they not see? This is why I thought I was set apart, chosen. Especially by you.

409.4 kilometers

was how far I moved, after her dismissal. A “rustication because of the Annual Day Function debacle,” the official statement seethed on our notice boards.

Bracts of interest, curling out of my palm. Flattened, the moment I saw the announcement. I felt no need to finish my degree, no need to return to the dim strobe of opiates and classrooms and apathy. I married my cousin. I couldn’t find a reason not to. The prince always returned home, even if the home that he knew unformed into an edgeless shape, utterly new. This was how it always was.

My husband was a man inured to family customs, his mind calibrated to only autosuggest whatever societal and cultural norm that was in vogue at the moment. He hated decision-making, loud noises, birds, television news anchors, overgrown plants—anything that declared its presence in full, that took up a lot of space. His days neatly cubbied into geometrical blocks of time that were predetermined by someone or something else—his bosses at work, his mother, the Fair Price Ration Shop that only sold lentils and rice for two hours each morning.

One evening, I stepped out of the bathroom and into the dining room completely naked. I did not desire my husband at all, but I did seek to provoke him. A tiny coil of satisfaction lodged itself in my throat at the idea of his shock, his discomfiture. Instead, his face held no reaction at my nude body, its willful intention.

Enna, he said.

Enna? I asked, in response.

Our whats hung suspended in the air, unclaimed.

Then he stood up without a word, walked over to the settee, and turned on the tv.

After that day, I understood that in marrying me, my cousin had reached his life’s purpose, his pristine adherence to tradition fulfilled. He did not care for anything else.

Somehow, I felt that this too was her doing.

108 days

of riverbanks, lakes, estuaries at the mouth of the bay, islets at the crocodile conservatory outside the city, pockets where bodies of water sheared land. The sloughed remnants of your scales, glasslike. I ran my thumb along the scutes of your belly at each waterfront, remembering how it used to be my teeth paring your human then snake then human membrane one after the other after the other, the saltmetal tang of your limbless form blistering the underside of my tongue.

At the conservatory, I befriended a herpetologist. Her muscles would pulse under her safari shirt as she rolled up her pant cuffs and tucked her long braid inside a bucket hat while cradling adult gharials in her arms. Somehow I thought this might be easy, and it was. All it took was three guided “Become a Zookeeper for a Day” tours in succession, and the herpetologist’s interest in me switched on like a heat lamp. It was the linear endpoint of a shared drink and a decision one evening, and what did it matter, my husband was remote enough to be an apparition, a non-presence.

Most importantly, she was not you. The herpetologist’s rancid sweat was like mine—all too human, her laughter a sonorous boom, her torso thick and unspeakably beautiful. But when she got on her knees in front of me, her arms encircling my waist, fingers unfurling into an orifice, all I could see were her specimens on the wall, a bas-relief of reptiles entombed in milky jars as my legs slung over her shoulders, tightening around her jawline. I would whisper the names of each bottle label as I bucked on her tongue. Checkered keel back, Bengal monitor, rat snake, mugger eggs.

Blue-lipped sea krait.

Blue-lipped sea krait.

Blue-lipped sea krait.

I would have known those markings anywhere. Known those blue-black bands to be a premonition.

2.6 meters

of high tide, waves keening against the bluff. I hulled the clothes off my skin as pain fisted around my purpose. A temple conch blasted on the shore below, the first shrill note to awaken a god. Conferences of large-billed crows and terns competed for silvery coins of dried sardines, karuvaadu as breakfast scraps.

I unscrewed the vial of krait venom filched from the herpetologist’s freezer, downing it in a gulp. A sudden vision of her braid, a pang, nothing more than a momentary diversion.

Holding your ecdysis in my ring-fingerless hand as blood dyed your cast-off life, I leapt into the murk of the sea.

You once said that I was not a prince. I now know this to be the truth, even as I scattered home to my husband who was my cousin. To the herpetologist. In the beginning that was the end, unlike the prince who was the son of Flowing Rivers and War, I chose the snake. I chose you.

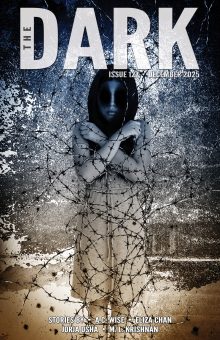

Originally published in The Crawling Moon: Queer Tales of Inescapable Dread, edited by dave ring.