Sometimes he’d wake up in the middle of the night thinking others were living in his house. Not intruders. Not burglars. They were full-time residents. They had voices too tiny to hear but put them all together and they suggested the most dreadful noise.

First thing in the morning Julius thought he could see them, but perhaps it was just an eyelash, a piece of lint, or a shadow cast through a window. Still, the belief persisted. Occasionally during the day, he would perceive something passing through the light, or lingering in some far corner of his visual field, or disappearing when he turned his head. He sensed their intelligence working nearby. These perceptions might have been due to his age or deteriorating vision. Or because both his memories and immediate observations were no longer trustworthy. Or he had reached a stage of life when he had finally earned the right to experience their presence. He was as alone as anyone could be, and yet he wasn’t.

As a little boy he’d experienced the outside world as a sea of constant, background activity oddly synchronous with his own internal restlessness. He’d had no problem with lying down in the grass and joining them, seeing the world from a bug’s eye point of view. At his age that felt inappropriate, and exceedingly difficult considering the severity of his arthritis. He might not be able to get up again. He imagined himself flopping around in the tall grass, an invitation to predators. But he could always look into his yard where a variety of species thrived. This was a good thing as far as he was concerned, although his neighbors might not agree. Even though his eyesight wasn’t what it used to be he could detect their tiny, anxious movements, especially where he tossed out some fruit, or a dead mouse, for them to feed on.

The imago is the final stage of an insect’s metamorphosis, the time when it attains its full maturity. In winged species it is the phase when the insect finally gets its wings. It fulfils its potential. Even though he was past seventy, Julius felt incomplete. He was still waiting for his wings.

He heard a thrumming noise rising and falling in waves, a message from the numinous if he had the means to understand it. But understanding was not always beneficial. They seemed to know when he was ill. They might even know how much time he had left. He didn’t want that information. He opened the door and stepped out onto the deep front stoop. He heard some of them buzzing past his ears, entering the house. He should be more careful. He loved them as much as he could love anything, but he could not afford an infestation.

A driver from the local grocery was coming up his front walk. Julius had everything delivered. He usually hid inside while they unloaded his order onto the stoop and didn’t retrieve his items until after the delivery person left. But today the delivery was early, and he was exposed, watching the fellow push aside the branches and fronds crowding the sidewalk, looking annoyed. Julius had collected a tall pile of notices from the city concerning the overgrowth in his front yard.

It was too late to retreat inside. When was the last time he talked to anyone face to face? He couldn’t remember.

The background symphony of insect sound increased significantly as the driver approached him. It was early April and Julius could smell Spring. The trees and bushes had begun to leaf out, but a thick tangle of bare branches and trunks remained, so many he wondered if maybe he really should trim things back. He couldn’t make sense of all those branches.

The driver, now only a few feet away, grinned. “Beautiful day!” he said.

“Is it?” Julius looked up. The air was full of tiny flying creatures. They might have been superheroes seen from a distance. “I don’t get out much.” Which was a lie. Julius didn’t get out at all.

“Let me bring these in and help you put them away. No charge.”

“That’s really not necessary.”

The grin grew improbably wider. “I’m happy to help.” His voice was so large it hurt Julius’s ears. When did people start speaking so loudly? The man was tall, broad-shouldered, sandy hair. One of the beautiful people. Julius felt like a gnome alongside him.

What had the fellow seen in him that suggested he needed special assistance? He wasn’t completely helpless. Not yet. The man pushed inside without further comment. It felt like an assault. Julius struggled to keep up. He was embarrassed by all the dust and disarray and the crappy kids’ cereals in his cabinets, the lack of fresh vegetables in the fridge, the lack of much of anything in the fridge, and all the pizzas jamming the freezer compartment (this order added three more).

“Where does this go?” The driver held up a bottle of spray disinfectant. Julius hated the idea of using the stuff, but someday deadly force might become necessary.

“Top of that tall end cabinet, above the trash can.”

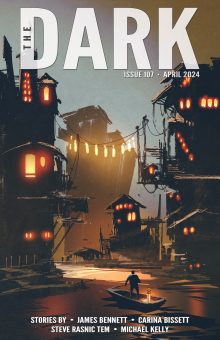

He’d always required a stepstool, but the driver reached it easily. “So, you like art?” Julius felt incompetent trying to follow the driver’s train of thought. Was this conversation? It had been some time since he had engaged in conversation. “The painting. That’s quite a painting. You know when I first looked at it I thought those were insects. They’re all over the place. What are those things?”

Of course. It was the only piece of art Julius had hanging in the house. “It’s a print of Fairy Twilight. John Anster Fitzgerald was the artist. I thought the same thing when I first saw it in a book. Fairies. Those creatures are fairies.”

“Like in Disney?”

“If you’re referring to Tinkerbell, I suppose so. In the original story she’s a tinker fairy. They fixed pots and kettles. The fairies had specialties. They—”

“Tiny, aren’t they? Fairies?”

“Not always. Some were human-sized, according to the tales. I think anything people couldn’t see or understand became a fairy in their minds. One of the legends is that when Christian missionaries sprinkled them with holy water they shrank.” Julius stopped. He didn’t know how not to be awkward. Here he was going on and on and the man obviously wasn’t listening. He remembered conversations in his distant past, burying potential friends with inconsequential trivia. He didn’t know how to speak to human beings.

In the painting fairies engulfed the rabbit, who reacted to their presence with unexpected calm. But animals have a different perspective. They must be exposed to strange phenomena every day.

He wondered if insects were why fairies had populated the human imagination in the first place. The world was in constant motion with all this vaguely visible activity. Wars were fought and carnage occurred all below eye level in these magical realms, by ethereal creatures humans struggled to name.

“ . . . lovely family.”

“Pardon me?”

“I was just saying you have a lovely family. Obviously, a large family. I envy you.”

For a moment Julius had no idea what he was talking about. Then with rising alarm he realized the man was studying the dozens of photographs he had hanging on the dining room wall and propped up on bookshelves and tabletops.

Julius paced back and forth as the fellow examined the photos, fighting the urge to grab the man’s arm and drag him away. “Thanks . . . thanks.” He went to the front door and held it open. Something flew by him, almost hitting him in the face. “Thanks for all your help. You’ve been great.”

“Is that your mother? Did anyone ever tell you she looks like that actress Helen Mirren?”

“Does she? I don’t go to the movies.” The fellow was walking down the line of pictures, touching some of the frames. “Thanks again.”

“There’s printing on this one, but the words have been crossed out.” The man’s nose almost brushed the glass.

“I’m sorry!” Julius didn’t mean to shout, but he felt desperate. “I’m not used to having people in my house.”

The delivery driver turned and walked toward the door. “I apologize. I was being nosy.” He appeared troubled and didn’t look Julius in the eye and Julius was sure he knew why. “Have a good day.”

Julius watched him sprint down the sidewalk. Something thin and stiff, an unidentifiable branch, reached out and attempted to snag the man’s shirt but failed. The driver disappeared beyond the mass of vegetation. A vehicle door slammed.

Julius walked over to the wall, straightening a few frames which didn’t require straightening. Of course, it was a photograph of Helen Mirren. She might have made an interesting mother. He glanced at a few of the pictures with printing. A happy, blond-headed child, but at a certain angle Julius could still read the 5 x 7 inches $3.99 barely detectable beneath the sloppily applied magic marker. Other photos were even less effectively redacted. He’d never seen families so happy or photogenic in the real world. But in the places where you bought picture frames such images were plentiful.

Of course, he had a mother. Or did. But he didn’t have any photographs of her. Families were supposed to support and encourage you. It was the one place to which you could always return. The decision to discard that portion of his life had made sense at the time, but now he wasn’t so sure. As you approach your final years you develop a hunger for context.

Julius ate a simple dinner of soup and crackers while gazing at his wall of friendly faces. Maybe it was time to find some new ones. Some of the old ones were looking tired, and it was becoming increasingly difficult to imagine any sort of connection. Was this the way pornography addicts felt? He had no knowledge of such things, and it dismayed him to have made the comparison. He didn’t feel right just throwing these people away. He’d either move them upstairs or store them in folders. They would become more distant acquaintances.

A Miller moth lit on one of the frames, and things much smaller crawled across the glass here and there. Were insects familial creatures? Were fairies? Did they crave some kind of connection with others of their kind? He had no idea. He did believe that the outside world was rife with cannibalism, all the way down to the microbial level. Dog eat dog. Sometimes in the natural world they devoured their own. Life was inherently cruel.

It seemed common knowledge that family relationships were difficult. But at least if you had family there would be someone around to find your body, though it might be weeks, or months, after your final stage had completed. Imago was also the word the Romans used for the death mask they made of the deceased. Some of those people whose faces adorned his wall might be dead. It bothered him that he didn’t know which ones.

A family might also let you know if you were showing signs of dementia. Julius considered his mental faculties intact, but how could he know for sure without corroboration? He had no one to compare himself to. Within his solitary domain he was king. He could set his own rules for proper behavior. But this seemed far too much responsibility for one man.

Faint music drifted in through the closed windows. Tiny voices. Possibly from a neighbor’s house, but they could be from anywhere really. The music might have been from some distant realm within his own home. He vaguely remembered a quote from the writer Clive Barker. “Always, worlds within worlds.”

Another moth landed on the table beside his placemat. At least it didn’t land in his soup. He should probably be more careful about leaving the front door open, but he was visited by these moths every year whether he was careful with the doors and windows or not. Perhaps they bred in his closets, or somewhere in the attic, or maybe beneath the floor boards. He nudged it with his finger. It did not move. He touched it again. It remained quiet and still. Did moths ever vocalize? Not around humans he supposed. Julius wasn’t sure he wanted to know what a moth might have to say. Had he somehow killed it, or had it died upon landing? Was this his fault?

He remembered as a child coming home with his parents after a movie. He remembered how much he’d loved that movie, but he now had no memory of the title or what it was about. They’d walked up onto the porch when the Millers attacked him. In hindsight he knew they hadn’t attacked. He’d walked into their flight path, and they’d simply scattered. But they’d struck his face and caught in his hair and clothing. He’d run upstairs and into the bathroom. He remembered scrubbing his face and crying. He remembered his mother telling him through the door to stop, that it was “no big deal.” The next day his father told him to stop being such a baby. He would never get anywhere in life otherwise.

He slid a sheet of paper under the dead moth and buried it deep inside his kitchen trash can. There was some sunshine left in the windows, but he was tired from all the excitement of the day. He no longer owned a television. Its tiny conversations quickly overwhelmed him. Most evenings he read, but tonight he was too tired even for that.

Millers fluttered across the wallpaper lining the stairwell, along with numerous drab-looking bugs he could not identify, a few stick insects, crawling creatures, scattered flying bits of nothing. Something touched him now and again. He assumed by accident, or had it simply wanted a taste? Julius could not remember the last time he’d been touched deliberately.

He hadn’t held the door open long, so he couldn’t imagine why there were so many bugs, assuming they were all bugs. Some were so tiny, they appeared to be no more than disturbances in the air itself. He considered again that their nests might be local, hidden with the recesses of his home. Suddenly they seemed everywhere. The stairwell was dark, and he couldn’t get close enough to see. The air gossiped around him. Perhaps they were commenting on his age, his obvious decline. Circling the drain, he’d heard people call it, but maybe they had words in their own language for an individual’s end. Their small lives must not last long. Their tiny hearts must beat furiously with the frantic knowledge of their brevity. He couldn’t help breathing in the dust their deaths produced. Perhaps he was consuming their bodies as well. He could be their cemetery.

Julius took a long shower to cleanse himself. The glass door was cloudy with limescale. He wanted to do better with cleaning, but he couldn’t afford a service. On the other side of the glass their shadows loomed, magnified by the distortion. He stepped out of the enclosure with his eyes closed. By the time he’d toweled himself dry they were gone.

Steam had left the wallpaper in the adjoining bedroom damp. He hadn’t noticed before, but there were large areas of bubbling. Did this happen every time he showered? He imagined if he peeled the paper away he’d find terrible corruption underneath. More of them, perhaps of a different species, living there. Entire colonies. A universe. The room became animated as they discussed his irresponsibility. He put on fresh underwear and pajamas. It wasn’t much, but it was something he could do to make himself feel clean.

Slipping into bed Julius watched the light through the windows as it dimmed, chasing the small bits of floating debris into shadow. The pattern of the wallpaper appeared to fade, its colorful scales disintegrating, gradually revealing a layering of membranous wings. The walls stirred and Julius pulled the stale bed sheets over his head.

He struggled for sleep and may have achieved it momentarily. They knew too much about him. He had run out of places to hide. They knew of his sluggish blood, his failing heart, the ever-widening gaps in his thoughts. He cowered beneath the sheets like a child, trying to ignore the constant rustling on the other side of the fabric.

Achieving sleep was always difficult even in the best of times. He was too aware of the noises the house made, or worse, the sensation of things crawling across his skin, as if his nerves had gone for a stroll. The tiniest movement in his hair, the most subtle itch, forced him to imagine what might be straying across his flesh. Most nights, sleep only came when sufficient exhaustion accumulated, the weight of it dragging him down into anxious dream.

Julius woke up to the heat of the day. His body was sticky, his pajamas soaked with his sweat. He felt as if steamed. He might have been running a slight fever: his vision blurry, his thoughts seemingly floating outside his head.

Outside, all those tiny lives were making quite a din. He knew that insect reproductive rates increased during the heat of summer. Perhaps the same was true of all those other small or invisible ones, those fairies and others human beings might not even have names for. Those communities beyond understanding. Whatever they were, Julius thought, they possessed more life than he.

He walked downstairs and stared at the photos of his manufactured family. His family stared back. The house felt empty. Perhaps all those others living here had gone outside to enjoy the sun. He began to shiver. His damp skin and hair. His wet clothes. His family seemed to be saying Don’t go out there. Stay inside with us where it’s safe. But what had playing it safe gotten him? Countless years of living alone. At least outside there would be warmth.

He opened the front door and stood on the stoop. The variety of insect noise blended into a cacophonous sigh. He felt a little self-conscious standing there in his pajamas. But no neighbors could see him, not with all these bushes and trees, and the other plantings crowding his front yard. His personal jungle. He stepped off the stoop and onto the sidewalk. The volume of insect noise abruptly increased, as if in exalted celebration.

Julius stepped off the sidewalk and into the high weeds between the bushes and trees. Remembering his childhood, there he fell to his knees, and although the weeds looked rough and uninviting, he let his torso fall the rest of the way, so that his head was on the ground, their level.

He knew he might never be able to rise again. His arms didn’t work well enough, and he’d lost the knack of going from his knees to upright on his feet again. He wasn’t sure how that kind of physical feat was even possible, even though he’d obviously been able to perform that small miracle of mobility for many years.

But here he was at last in fairyland, a Gulliver asprawl across so many miniscule lives. Although his vision was still somewhat blurry, he could see the kings and queens of fairyland, and all their soldiers mounted on the backs of crickets and snails. He couldn’t understand their language, but he could feel the emotion in their words, as well as the stings and slices as they attacked him with their tiny knives and spears. He expected the blow flies and the flesh flies to arrive soon, and all those beetles and moths. Eventually they would find their path throughout his flesh, a thousand wings carrying the final bits of him up and beyond.