“So, is it all coming back yet?” Ursula Crichton’s question snaps Dan back to the here and now. Tires grit on tarmac as she eases the Subaru estate around a corner, a bar of spent sunlight scanning across her face. Outside, brambles and browning gorse overhang moss-scabbed walls. Branches of birch and oak shiver above, clinging on to the last of their leaves, and in the woods’ deeper shadows loom spruces and Scots pines. At some point she’s rolled the windows down half an inch and the air is cold and sharp with autumnal moulder.

Despite a lifetime of promises there’s no doubting where he is. Memories of it, though?

As kids Ursula and Dan were friends but this middle-aged woman in a North Face fleece and no make-up, her scrunchied-up hair threaded with wires of silver, is a stranger. She glances over with bark-brown eyes. Dan has been trying to recall since she picked him up at the station, but can only picture a cheeky, stork-legged teen in denim shorts and an Aberdeen football top. He vaguely remembers thinking that he might have fancied her if her hair were cut like Dee Hepburn’s instead of Clare Grogan’s but not what colour eyes she had. Likewise, he can picture in his mind almost nothing of the village that lies along this winding Argyllshire road. Never had a reason to want to remember it, so it’s long gone. Discarded, junked, along with the rest of his childhood.

Dan makes himself smile. “Starting to, yeah,” he says. “It’s good to be home.”

Ursula grins, the sun sliding off her face again as they enter a cloister of tree shadow and lapse back into the ill-fitting silence that so far has characterised their reunion. Back to the stereo’s nineties indie mix, tinny over the road rumble. Dan’s recognised few of the tunes. By the time of Britpop, he’d already escaped to Glasgow. Business school and club culture were the scratch and flare to his life, the fizzling touch paper that launched him into the world of banks and security software: the job in the City of London, the Jacob’s ladder of promotions, the house in Highbury complete with Home Counties wife and kid, business class travel and expense accounts, living the good life—the best life—wherever he happened to be and with whomever he fancied. Strategically calendared vacations in Disneyland Paris and on Barbadian beaches. The condo with the pool that English Sara didn’t know about, but Californian Courtney did. It had been a blaze, every second of it.

It was never fucking meant to lead him back here.

It’s only when the Subaru passes a pair of gate posts topped with stone pineapples and then swings through a particularly lurching right-hander that anticipation unexpectedly clutches Dan’s breath. He thinks cattle grid a second before they rattle over one, and bow-backed bridge just as they emerge out of the trees and rise over the old stone arch. And that’s when memories start to resurface. As they cross the River Afton, he remembers skimming stones in the late summer, defying his mother’s warnings for the joy of raising white lips from the brown water. When they pass the sign that reads Crawfoot, he remembers pretending to patrol there with Ursula, sharing a borrowed air rifle like sentries in a war movie. And when the car squeezes through the narrow choke that he knows will feed into the bottom end of the Mains, they pass a two–storey building with boarded windows, a rusting roller door and a dilapidated petrol pump, the red and white ESSO all but scratched away. The garage’s signage has been taken down but Dan remembers the name of the girl who vanished playing near the woods, there and then gone one trick-of-the-light autumn evening. That name, a warning and a prayer around the village for months afterwards: Christine Hutchison. Fuck, he’s not thought about Christine Hutchison in decades.

They’re flooding in now. He remembers standing in the kitchen of the old house, staring at the drab olive Formica while his Mum lectured him about wandering around on his own. The house is a few streets from here, through the Mains and past the school. He remembers the redbrick garden wall and squealing gate. Their living room with polystyrene stonework around a two–bar electric fire, like a cave of modernity. His bedroom wallpaper, aeroplanes among the clouds, pasted up over a horrendous green flock that his curious, picking fingers had disinterred behind his headboard in his early teens. He remembers the unpleasant fuzziness, soft like an over-ripe peach. His Mum had done her nut when she’d found out.

Dan makes himself stop. He blinks, breathes, licks his lips and acknowledges that his childhood hasn’t been discarded after all, just buried beneath layers of better memories over the intervening thirty–five years, pasted down determinedly but still there, ready to be revealed in rips and strips. He swallows, feels saliva flood around his parched, beach-wreck of a tongue.

After the garage, the revelations continue at a more sustainable pace. As the Mains opens out like a dusty photograph album, he sees the old church at the low end and the primary school at the high, both exactly as he remembers. The parade of shops strung between them, though, is a sorry sight. The butcher’s is still there but the grocer’s is now a budget supermarket, its window plastered with dayglow deals. Further along, the baker’s has become a knock-off Greggs, and the sign above McKee’s Newsagent, where Dan, suddenly, vividly, recalls buying Kwenchy Kups and Monster Fun on sun-soaked Saturday mornings, just says GIFTS now, barely a step up from a charity shop. He can’t remember what used to be where the grubby café is and several of the remaining premises are derelict, giving the impression of an old man’s leery grin. It’s just after five in the afternoon but this deep into October the street lights are already on. There are few souls about, and they huddle and scurry through the gloaming as if eager to finish their business and get home.

Ursula noses the car towards a parking space. “Just going to pick up a couple of things,” she says. “Want to come?” Dan shakes his head. She holds his gaze for a second, the skin around those brown eyes delicate as leaf skeleton. “Right you are.” Grabbing her purse from the dashboard, she ducks out of the car and strides off towards the supermarket.

Dan waits until she’s inside before he gets his phone out. Just two bars of signal but knowing he’s not completely cut off he breathes easier. He opens Facebook and sits for several minutes trying to think of something to say. Fuck’s sake. How hard can it be to post a photo of this shit hole and tap out a sarcastic note about how much things have gone downhill? Is he ashamed to be here? Is that what it is? Ashamed to leave the car out of fear that someone will recognise him? Ashamed his colleagues will judge him for his crappy beginnings?

Well, fuck that. He’s proud of what he’s made of himself. Because of his crappy beginnings. Angrily, he starts to tap something out but a bubble of emotion wells in his chest. His eyes feel gritty. He blinks, breathes, deletes what he’s written.

The truth is . . .

The truth . . . is that it’s not Crawfoot. It’s him. Since the promotion and all that came after it he’s fallen out of the social media habit. He used to be such a proud man. He doesn’t have so much to be proud of any more.

Instead of posting a message of his own, Dan scrolls through his feed. Ursula posted a link to some local produce initiative an hour ago, but nothing about meeting an old friend. Since their unexpected reconnection a few months back—her embarrassingly tentative I don’t know if you remember me—he’s learned that she’s not an over sharer. Maybe she doesn’t have much to brag about either. That’s something they have in common at least.

Of his actual friends, the Americans already feel remote, geographically and socially. It’s barely been four months since his step up to European VP. The permanent move back to the UK is supposed to be a reward, a well-earned opportunity to spend time with his family while younger colleagues burn themselves out hitting the targets that’ll earn him his bonuses, but it’s all gone wrong. Somehow, a tear has appeared through his carefully layered lives and something has seeped through—Sara meet Courtney—and now he’s unwelcome in either of them.

He likes a picture of one of his colleagues’ kids playing with the family dog in the front yard. Goofy pumpkins on the porch in the background. SoCal in the Fall. Movie shot idyllic. He really misses it.

He turns lastly to his English friends. Most of them were Sara’s crowd and he feels grubby flicking through the streams of those mutuals who haven’t completely cut him off yet, but he makes himself do it and is rewarded with snaps of Oliver at the nursery Halloween party. The wee fella’s done up in a garish costume. Some cartoon character Dan doesn’t recognise. He wants to like it, to heart it, to make some mark so that Oliver might know.

He wonders if this is what it feels like to be a ghost.

Dan puts his phone away and gazes out of the window. Ursula is taking an age in the store so he allows his attention to linger on a young mother struggling to drag her child past the coin-operated aeroplane outside the gift shop. There are stern words but the kid—about Oliver’s age, the blonde hair shorter and a shade lighter—has dug his heels in so Mum relents and fishes out a pound. The tears turn instantly to laughs as the machine jiggles into motion. Dan realises he doesn’t know if his own son would find such joy in something so simple. The mother intermittently checks her phone and glances hostilely around and, when she spots Dan in the car, she stares until he looks away. Next door, they’re switching the lights off in the café, the owner, about Dan’s age but with a shag of greying curls and a paunch overhanging his jeans, ushering the teenage waitress outside so that he can lock up. She hurries off without even making eye contact, and the owner watches her for several seconds too long before jangling the keys towards the lock.

The aeroplane ride is over and the mother is now talking to Ursula, from whose hand dangles an unbranded carrier bag lumpen with groceries. Dan hopes she’s not gone to the trouble of planning something elaborate for dinner. He doesn’t want her to try and impress him. It’d be embarrassing. His face flushes as that ugly thought buds and blossoms from the branch of scorn that has burgeoned while he’s been sitting here.

Jesus, Danny, he thinks. Try not to be too much of a dick while you’re here.

The mother and child depart but, before returning to the car, Ursula pauses to look at the aeroplane. No, at something behind it. In the evening gloom Dan has failed to notice it until now. It’s like ripping off several layers at once.

The tumshie tub.

The old-fashioned hoop-bound barrel is shoved up against the wall, its iron rusting, its wooden struts green and crumbling. Ursula drops a coin into the Baxters soup can dangling from the barrel’s rim and then reaches deep inside to pull out a muddy, wizened turnip.

“Fuck’s sake,” Dan mutters aloud.

Ursula is smiling as she crosses to the car and opens the door. Hands him the shopping bag so she can slip into the driver’s seat, and then the turnip too. It’s the size of a child’s head, a shock of slug-ragged leaves sprouting from the top. Mud crumbles onto Dan’s Kühl jacket.

“Remember now?” she says.

Memory, Dan thinks after fake-smiling through a dinner of microwaved rogan josh and awkward reminiscences, is a fucked up thing. What it chooses to show you, what it keeps hidden. What peels away easy and what’s stuck down hard. He can recall the feel of his old bedroom walls acutely, the fern patterns inlaid in the vegetal green. He must have been to Ursula’s family home—hers and her husband’s now—dozens of times but it’s entirely unfamiliar. They’ve talked for over an hour and it’s been stilted and frustrating. He doesn’t remember the things she thinks he ought to. He doesn’t want to talk about the things he does.

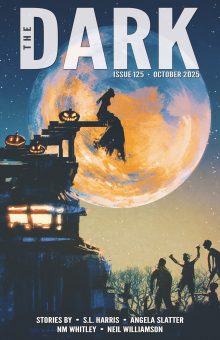

Especially the Warding, Crawfoot’s take on the traditions of the season. Halloween when he was growing up had none of the fun that it has in America: no pumpkins or trick-or-treating, no parties, no cosplaying superheroes or film stars. It was serious business. During the week leading up to All Hallows, the village kids went guising to their neighbours’ houses. They’d wear sackcloth masks or ash-blackened faces so that they could pass for the spirits of the dead and carried a joke or a song to prove their humanity and earn an apple and a handful of nuts and sweets. Even so disguised, no child was allowed out without a turnip lantern to ward them. And not just any turnip either. It had to be taken from the tumshie tub and paid for with honest-earned coin. On Halloween night itself, an adult walked the Ward for the ‘good of the village’. No-one else. That’s the story anyway. It came up several times in the conversation but he didn’t pursue it.

It’s only now while watching Ursula across the cluttered kitchen table, working determinedly with knife and spoon to hollow the turnip out, that Dan is hit by a memory that punches right through to his soft grey plaster.

He’s quite young because the garden wall is as high as his shoulder. A rowan tree dangles overhead, red berries glistening under the streetlight like winter poison. His nose is running from the cold and the air is bitter with bonfire smoke. As he totters after the other kids he can feel the candle inside his lantern rocking, its light guttering with every step, so he’s gripping the string tight and trying not swing it for fear that his fierce-grinning protector will snuff out. As he ducks under a branch he feels something touch his hair. He freezes but can’t bring himself to turn and see if it’s a rowan twig or Herself’s questing fingers.

Fucking hell.

Dan takes a long gulp of his wine. “I can’t believe you still do all this,” he says, trying to make his tone light but doesn’t think he’s quite succeeded. “The modern world still not quite made it to Crawfoot yet?”

Ursula glances up from spooning yellow flesh into a brimming Tupperware. Its sweet, organic smell mixes with the stale spice from the plates that are wedged in between the sheaves of home-printed flyers for farmers markets and Shop Local weekends. “Hardly,” she snorts, glaring. Looking away, Dan’s eye falls on a stack of adverts for a local business forum. The paper is water-stained, the date some weeks in the past. “A Starbucks here would be a fucking tourist attraction.” She resumes scraping, but has something to add. “Actually that’s something I wanted to ask you about. Investment, reach, visibility. You know about that stuff, Dan. How do we do it here?”

“Ha!” he exclaims, half out of surprise, half relief, because at last he gets it. Sees all of this for what it is. Thank fuck. Ursula’s been fishing, attempting to hook him with nostalgia. Trying to get him invested so that maybe she can persuade him to invest. She’d chosen a clumsy way to go about it, picking around the edges, trying to find a corner that’ll peel, but without success. Until that unexpected memory of guising just there. He won’t deny it shook him, but finding out that there’s a mundane, cheap-ass reason for Ursula’s invitation to visit makes it almost laughable. This is the sort of duplicity he understands. “I knew it,” he laughs. “I knew there was an ulterior motive for all this.”

Ursula has a thing she does when something perplexes her, a sort of grimace between a frown and a smile. She’s doing it now. “Seriously?” she says. “You couldn’t just believe I wanted to catch up after all these years? Maybe rekindle a fucking friendship that once meant something? To me at least. Sorry if I’ve overstepped the mark in asking for a little advice.”

Her defensiveness irks Dan. Why is she keeping up the pretence even after he’s called her on it? Is it face-saving? The village is dying on its arse because anyone with any sense leaves it as soon as they’re old enough to hitch a ride out. They always have. “You’re asking for the benefit of my experience?” he says. If it sounds patronising, he doesn’t care. “Well, yeah, in my experience there’s always an ulterior motive.”

“Is that so?” Ursula tips out the last of the turnip’s innards then examines the exterior, tracing lightly with the point of her sharp little knife. Feeling the natural contours of the rough skin. She’s looking, Dan recalls, for The Face. Making her choice, she stabs deftly through the skin, then again at an angle to the first cut. After the third incision, a triangular plug pops out, leaving a crude eyehole. That’s how it’s done, he remembers. Your tumshie gets none of the Instagrammable artistry afforded to the fabled pumpkin. Ursula makes to slice out the second eye but instead she points the wicked blade at him. “All right then, what’s yours?”

“My what?” he says, surprised.

“Your ulterior motive. Why did you come here?”

“Because you asked me.”

“Simple as that?” she scoffs. “You don’t know me. We’re not friends and whatever history we shared, it is clearly long forgotten. It wasn’t even a direct invitation: You should come back some time and visit,” she parodies her own voice. “People say that sort of thing all the time. It’d have been easy enough to say you were busy with work or didn’t want to leave the family or . . . politely, say you had no interest in setting foot in this God-forsaken pit ever again, but you didn’t. You jumped at it. You were practically on the next train up. Why?”

Dan deals her a boardroom stare but she doesn’t even blink. He takes another long swig of his wine and swallows slowly. There’s a sour edge to it that’s starting to curdle his stomach. Of course, she’s right. There was no good reason for him to come here. Even when Mum was alive, Home had been that pretty little cottage she’d moved to in Perth and, when she’d ever mentioned Crawfoot, it had been to curse the place. She never mentioned his Dad either, except that one time when he was very small and full of questions. He went away before you were born, son. She’d said it matter-of-factly, without rancour. And he’d accepted it because theirs was far from the only Crawfoot family that’d lost a limb somewhere down the line.

Eventually, Dan says: “So, how long did you say your husband was away on business for?”

Ursula’s laugh is a howl. “You always were a cheeky fucker,” she says, grinning as she goes back to carving the face.

Dan laughs too, or at least pretends to. Thing is, he doesn’t even know if he was joking. A random fling? Really? Is that what it’ll take to make him feel like he’s got some sort of control over his life?

The moment has broken down something between them though. He reaches for the bottle. “Top up?”

Ursula glances up from knifing out a zig-zag grin. “Sure . . . ow! Fuck!” Her blade’s been too eager and there’s blood beading on her finger. She sucks it off, then shakes the pain away.

Grimacing, Dan upends the bottle over her glass. There’s barely a dribble left. “Sorry for distracting you,” he says.

“Don’t you remember?” she says. “A little blood lends the Warding that wee bit more power.” When Ursula turns the turnip around to reveal its ugly face, sure enough there’s a tinge of pink on the serrated teeth.

“This is stupid,” Dan blurts, and then recoils from the gust of boozy vapour he’s just expelled. The stink of it even overpowers the burnt cork Ursula used to paint his face. They’d exited the house looking like commandos, giggling, eyes alight. It’s less funny now as they creep past the old garage. He leans against the wall for a moment, silently cursing the speed they’d consumed that second bottle of wine and the eagerness with which they’d then moved on to the whisky. “C’mon, man. Halloween’s weeks away yet.”

“It’s close enough.” Ursula’s voice shimmers off the bricks from a distance ahead. There’s no street lighting, so he can only see her by the light of the turnip’s glaring devil grin. “These days we walk the Warding as often as we can. Herself’s got greedy since you left.”

She’s just fucking with him again, invoking Crawfoot’s own bogeyman: the supposed witch of the woods, blamed over the years for stealing the unwary and for any other general misfortunes that befell the town. A lazy amalgamation of folk tropes. Shit, they couldn’t even come up with a decent name for her. Ursula’s going to have to try harder than that.

He pushes off the wall and in the darkness almost walks into the old petrol pump. Below the rotary dials that once counted the gallons, exposed here like teeth in an excavated skull, there’s a sticker: “Licenced to H&G Hutchison, 3 Mennie St, Crawfoot, Argyllshire”.

Christine Hutchison got took by Herself. Thanks be to her family. The phrase echoes unwillingly in his ears. It’d been the village mantra that whole year. He remembers the fruit baskets and fresh loaves, the discreet visits and kind words visited on the family like they’d become holy or something. He remembers . . .

It’s the Halloween night of the year after Christine disappeared. There’s a crowd of them, young teens. A nervy knot of giggles and bravado. They’re too old for guising, so they’re going to walk the Ward. Do their duty, like the adults do, in Christine’s name. They’d all known her a bit at school, but their ringleader, Moira Lennox, had been her best friend. Their parents would have forbidden it of course, so they’ve all sneaked out, using their teenage logic to convince each other that doing it together—doing it for Christine—means they’ll be okay. They all say they’re not afraid but Dan can tell they are. He is too, and he doesn’t even believe in it. Even, or especially, despite what they’ve been saying about his Dad recently. They’re eejits when they want to be but they’re his friends. All the same, there are limits.

Moira had rummaged through the tumshie tub with such care, scrutinised every ruddy skin until she found the one with the right face. Now, as they follow the lantern single file past the garage, the mood becomes solemn. Dan loiters at the back, not really sure what he’s doing here. What any of them are doing, really. Only Moira’s motive is clear, the lantern light illuminating her anger. Even without it earlier, her face had been glowing with defiance. The rest of the faces, as they shuffle through the choke, are pensive, each contemplating the real darkness outside of the bounds of the village and what, in their hearts, they either do believe or don’t believe or half believe, waits. One by one, they file out into the dark, the cheeks of some of them, Ursula included, glittering. Doing their duty.

But Dan . . . can’t. All of this is stupid, pointless. It’s irrational.

And he’s sorry, he’s sorry. He’s so sorry.

Those are his thoughts as he runs home, his skin electric with the anticipation that any second something will reach out for him. To touch his hair, perhaps, or stroke his neck. Or, worst of all, cradle his skull. Sizing it up.

Ursula has reached the town sign by the time he catches her up. “This is stupid,” he says again, out of breath. It’s really cold out here, the sky overcast and the stars hidden, a dampness in the air. It is stupid. He shouldn’t be here. He should be at home, working out what to do with his life. Trying to patch things up with Sara or calling Courtney and telling her this time he’s really going to do it. Jack it all in and emigrate. He needs to be strategizing. Consolidating or moving on. He’s not too old to start from scratch again. The Gulf maybe, or Australia.

“It’s just a tradition, Dan,” Ursula says. “You’ve come all this way. One short walk around the village is the least you can do.”

All right then. Just once round the village, bridge to bridge and then home. A night on the sofa and he can call out an Uber in the morning and be done with this. Nothing will happen.

“So, yeah,” he says, following her off the road and along the rabbit path that runs through the pale whin towards the river bank, “I can probably sort you out with someone to talk to on the promotional side of things and I know some shit hot fundraisers too. They might have some ideas you can use.” He’s rambling, he knows, but it’s better than thinking.

“Really?” Though she’s only a few feet ahead of him her voice sounds distant. There’s no breeze, it’s just her passage that’s making the grass dance in her wake, strobe–like in the lantern glow. “That’d be amazing.” The last word is muddied by the trickle and plash of water to their left, the creak of branches. Dan peers but can see nothing beyond the grass. There could be anything out there. To his right he can just about make out the silhouettes of houses. All the lights off, the windows dark like shut eyes.

“No problem,” he says, and now his own voice sounds thin out here too, diminished and tenuous. He presses on regardless. “Though to make a step change, an area like this really needs some proper investment. A draw. Food tourism is big right now. Maybe you could get some development money to open a distillery? Whisky, craft gin. A shop to sell local cheeses and smoked meats?”

Ursula doesn’t reply for a moment. Then: “I’m not sure that’d work here. Don’t think She’d like that.”

No, don’t say that, he thinks. Don’t bring Her into it. Don’t give me an edge to pick at.

They’ve been walking a good ten minutes now and should be following the river bank up around the western side of the town, but they’re still in the long grass. It caresses his legs with every step.

“Ursula?” he says. She says something back but he can’t make it out. “Ursula!”

She pauses, raising the lantern as she looks back at him over her shoulder. In the ruddy glow from its impish eyes, her grin looks like a rictus. Her voice is suddenly pin sharp. “We’re nearly there.”

He wants to believe she means nearly home. They’re just walking the Ward. Once around the village.

Nothing’s going to happen.

He never asked Mum if it was true what his friends said happened to Dad. And all the others from the village who were found wanting. He didn’t need to because he doesn’t believe in it.

He doesn’t.

“Here we are.”

Yeah, there they are right enough. Fuck.

The grass has thinned out, revealing to their meagre light not the riverbank path but a rectangle of turned mud the size of Ursula’s back garden. The little field is coarse and cloddy but isolated clumps of scrawny leaves poke through here and there. Standing before the field is a rusty wheelbarrow with a garden fork balanced against it.

In the centre of the field is a house. Or something like a house. It’s a single storey high and in an awful state. Its roof slates are leprous with moss. Its lintels crumbling. Its bricks are in the process of being crushed ever so slowly by a prolific woody vine. There are no windows and just one door, which is too small for a normal person and has peeling green paint . . . and stands ajar.

“No,” he says.

“You can’t say no,” Ursula replies.

“I don’t want to.” Like a child.

“You have to. It’s why you came here.”

“No,” he says again and tries to turn away but she shoves him in the shoulder and he stumbles into the wheelbarrow and the fork falls with a scrape and a dull clang that sounds so loud out here in the dark that it almost stops his heart.

“I guess we discovered your ulterior motive, Daniel.” She’s grinning again, underlit by the rosy flicker and he can tell she won’t back down from this.

“Will you wait?” he says.

She lowers the lantern gently to the ground. He can see the scorching around the eyes and manic grin now, and a crack of light around the top indicating that the lid has shrunk from being cooked over the candle flame. The way she folds her arms tells him she’s not going to wait until it’s burned up completely. “Sooner you go, sooner it’ll be over,” she says.

What choice does he have?

He nearly has to squat to squeeze through the door but surprisingly there’s room to straighten up on the other side. And there’s light too. He’s not sure where it’s coming from, and there’s not much, but it’s enough to see the short hall that stretches in front of him. The stairs at the end. The hallway smells of turned earth and as he progresses down it he realises that he can touch both walls. In patches they feel soft and fuzzy like over-ripe peaches. Mostly they’ve been stripped back to the bare brick. Underfoot, twigs and pinecones scatter and snap, or something that feels like those anyway.

The stairs rise into darkness. There can’t be many of them in this tiny house but as Dan climbs he quickly loses count. He climbs until his calves complain, and with each heavy upward step the earthy aroma intensifies. He climbs until he forgets why he’s climbing, until the smell of soil is so strong it feels like his nostrils are plugged with it.

Then he is at the top, and he’s standing in a room whose ceiling is the earth. Skinny roots dangle down. White. Atrophying. Scraps of filthy cloth cling to them, like the last of the leaves.

And Dan stands there, waiting for the touch. The bark-brown fingers cradling a head fat with memories.

Weighing it in judgement.

Originally published in Shadows and Tall Trees 8, edited by Michael Kelly.