“They say there are only old women left.”

Dima, sitting on a stump, dirt and dead pine needles at his feet, hugs his greatcoat tighter around him but it’s no use. The cold is unspeakable. He’s never felt anything like it, would be ashamed to say so even though he suspects the others feel the same. Pasha, across from him, also on a stump, is hunched so close to the small fire, there might be signs of smoldering coming off his boots, but it’s hard to tell in this strange dusk. Hard to see much at all. No snow, not yet—how can it be so fucking cold with no snow?—but there’s something in the air, not quite fog, almost a veil.

Or maybe he’s just tired. Too tired. Scant sleep these past nights as they’ve traipsed into territory for reasons that seemed obvious at one point. No sleep, really, with the noises around them—if it’s not the ear-splitting cracks of weaponry trying to destroy people and buildings (admittedly it’s a day since that was heard), it’s the quiet noises in the depths of the blackness. Light breaths and hard, twigs breaking, the flap of wings. Whispers.

On balance, he thinks the quiet noises are the worst.

“They say all the men died—quickly. But the women . . . even when they were made to leave, when they herded them on buses and took them away for treatment and testing . . . ” he sniffs, thinks of his grandmother, “ . . . even then the old women came back. Escaped facilities, crawled from windows, under barbed-wire fences. The ones who knew they’d die anywhere else.”

“They say, they say, they say.” Pasha’s angry, but that’s his friend’s default setting so Dima doesn’t pay him any mind. Pasha, his dark curls hidden beneath a hat with furred earflaps, glares. Dima would kill for that hat. He pulls his own beanie down tighter over his nondescript hair, his undistinguished forehead.

“They weren’t old then, of course,” Dima continues. “Or not so much. But they had nothing else to lose. No other place to call home. They didn’t want to be in the cities, they didn’t belong there. They’d grown out of the forest, you see.” Dima knows he’s starting to babble. Doesn’t know why he’s telling this tale. Nor does Pasha, apparently. Only they’ve been waiting for Kolya, and Dima wanted to fill the silence.

“Then where are they? Hey? These old women?” Pasha shakes his rifle, but not at Dima, merely in his direction, the barrel pointing out in the woods so if it were to go off, only a tree would be harmed. He’s not that pissed off. Yet. “Huh, Dima? Where?” He makes a noise of disgust. “Fucking bumpkin.”

Before matters can go further downhill, Kolya steps from between two trunks, seems to appear by magic, as if pulling himself from the rapidly darkening air. He’s grinning; always the peacemaker, even when they were at school together. His bright blond hair catches the firelight, his eyes flash blue. So handsome. “Calm down, Pasha.”

“What are you so fucking happy about?”

Kolya holds up his prize: two rabbits. Poor specimens, and wherever his bullets hit there’s not much left. Kolya’s a city boy, wouldn’t know how to tie a snare to save his life. Even if he did, Dima’s not sure there’s a rabbit alive sufficiently stupid to step into one of Kolya’s traps. Mind you, Dima’s no country boy either, but he knows enough to know he knows shit. He’s glad he’s still got a couple of ration meals left, and that packet of biscuits. Surely that will be last them to the end of this trek? Surely tomorrow they’ll be out of the forest. Out of all these fucking pine trees.

They look so straight, so forthright with their vertical trunks, they grow so neatly, you think—then step into them and discover the lie. The trees, Dima’s certain, move. Like a gang of women in a bar, moving in front of you so you can’t follow their friend. Like a shield wall—by the time you get through, the one you sought has disappeared. But these trees: You keep walking, keep pacing further in because you’re sure you can see light somewhere there, just a little way off. Just a little. A tiny bit more. One more step.

And you’re gone.

They’d been lost three days now. Compasses don’t work here and there’s no mobile signal; even if there were, their phone batteries are long dead. Their watches had stopped telling them anything useful, supplies were dwindling, and Kolya insisted on trying to catch rabbits each afternoon before the light was spent. Today’s the first time he’d succeeded.

“Well done!” shouts Pasha and it’s not clear how much is sarcasm, how much is glee. “Tell me, Kolya. Did you see any old women out there? Dima says the woods are thick with them. Runaway old women. Wild creatures with their scarves and gumboots. Cavorting beneath the moon.”

“I said nothing about cavorting!” Dima protests, but the headscarves and gumboots aren’t too far off the mark. Imagines his grandmother again, so many brightly colored headscarves, she didn’t have to wear the same one for almost two months. When she died, Dima’s aunt sewed the best of them together to make a shroud. The other sisters called it a waste, but Aunt Sophia shrugged and said the young women didn’t wear such things anymore. She gave the rest to Grandmother’s friends to divide among themselves.

“Hush, Pasha. Build up the fire, let’s make a spit for these.” He dumps the bodies in front of Dima. “Skin them.”

“Me? Why me?”

“I caught them. Pasha is in charge of the cooking. You are the skinner, Dima. It’s only fair. A clear distribution of labor.”

Later still, only Dima is awake. The other two have rolled themselves into their sleeping bags and are snoring. They ate the rabbits, but Dima did not partake, couldn’t bear to eat the creatures he’d dressed for the fire even though the smell was tantalizing. He doesn’t mind taking first watch though; he really won’t be able to sleep anyway, is too wired. So, at midnight or thereabouts, when the old woman appears next to him, Dima almost shits his pants.

“Good evening, young man. I hope I did not startle you. May I share your fire?” Her voice is mellifluous, gentle. Calming. He’s not surprised she’s come to their encampment, dressed as she is in a pair of khaki trousers, long-sleeved shirt, and a sleeveless puffy vest—nothing more. Army issue, he thinks. Perhaps her own, perhaps a husband’s repurposed. Stolen. Whatever: Who is going to police such a thing out here?

“Of course, Grandmother,” he says, bestowing the title from an ingrained automatic respect. “Would you like my—”

“Keep your coat, boy, I do not feel the cold.”

He’s grateful and ashamed—it’s too chilly, really, for chivalry—then rises, offers his seat. This she accepts. He takes more branches from the pile of kindling collected that afternoon and adds them to the fire, careful not to overwhelm it and snuff the flames. Then he sits across from her, where Pasha had been. The stump is frosty, unwarmed by any backside for some time. Uncomfortable. His own was also uncomfortable but at least he’d been there long enough to make it toasty. He hopes his guest appreciates it. Settled now, he asks “Are you lost?”

She smiles. The fire splashes orange into her silver hair, makes deeper shadows in the wrinkles on her face as if she’s a relief map of life. Not ugly, strangely lovely. “I live here.”

Dima’s excited. “Your house is nearby? We haven’t seen any dwellings in three days! These trees—”

“I live here,” she says again. “But what are you doing here, young man?”

“We were—we got lost. We were looking for something. But the trees . . . ”

She leans toward him, closer to the fire, and sniffs as if she can smell his skin. Her hand reaches out, above the flames, gestures. A shiver travels down his spine, but he obeys. Offers his own hand, feels her fingers on his wrist almost as if she’s seeking his pulse. An expression flits over her face, awkward as a bat, and is gone.

“There’s part of you that began here,” she says, head tilted.

He nods. “My grandmother came from a small village that’s close by—should be close by.”

“One of those removed,” the old woman nods, “who did not return.”

“No.” Dima feels a little ashamed again, but isn’t quite sure why.

“This is no place for you,” she says, releasing him.

“But you just said I belonged here, a little.” He touches where her fingers were, finds the skin smooth and hard as if frozen or scarred. He must stop himself from looking down because it would be rude, and he senses this is not a woman who’ll let that pass.

She’s shaking her head. “No. A little of you began here. That’s not the same.”

His bottom lip trembles and he stops it. Tells himself he’s a dolt. Why take this as rejection? From an old woman he doesn’t know? Pasha’s right: He’s an idiot.

He clears his throat to ask what’s hovered at his lips since she appeared. Hadn’t wanted her to think him a coward (deep down Dima knows he is one) but the night is so very dark and he’s so very cold, and she’s beginning to seem so very strange. He notices, now, that she’s not wearing any shoes, and her feet look . . .

“Do you know the direction out?” he blurts. “Can we come to your cottage and use the phone? Call someone to collect us? We’ll be no trouble.” The idea of a proper roof over his head is intoxicating.

“I have no phone. But I will offer you the route home, for the memory of your grandmother.” He follows the sweep of her hand as she gestures off to her right.

A path.

A clear, bright, white path.

A path made of stars, he thinks, lining the forest floor like a silver carpet. Is he dreaming? He can see all the hundreds of miles they’ve trod to get lost—he can see the way through, the way home to the apartment where his mother and sister wait. Dima smiles with relief. Whether he’s dreaming or not, the feeling of hope inside him is warming.

“Thank you, Grandmother!”

“You simply step on the path and you will find yourself home, wherever that happens to be. But there’s a condition.” One of her fingers rises, a warning; it’s a stumpy digit, crooked and arthritic. He wonders how she copes with the cold in her bones out here.

“Condition? Anything, Grandmother.” There’s always a price. Besides, he’s dreaming. Isn’t he? He pinches himself. It hurts. He’s awake. He doesn’t care; he will take any magic as long as it gets him out of this fucking forest.

“You must go alone.”

Dima stares at her, glances at the still bodies of the others—they’ve known each other since they were five; they bicker but they are his brothers-in-arms. He has obligations. “But . . . Pasha and Kolya.”

“You walk alone, Dima, or not at all.”

He thinks perhaps he can persuade her, if he talks to her long enough, is charming enough, he can wear her down. “I can’t go without my friends, Grandmother.”

“Then you will not go at all,” she says—he likes to think a little sadly—and she is gone.

Dima is less afraid. The forest is filled with strangeness, but she did not hurt him. Not the worst thing he has imagined for himself. And tomorrow the sun will rise. They will find their way.

It’s only after he’s woken Pasha for his watch, when he himself is snug in his sleeping bag and drifting off, that Dima remembers he did not tell the old woman his name.

In the morning, Kolya is missing.

At first, they don’t worry—the fire is out, and they assume he’s off to find more kindling. But as the dawn burns through the clouds above, as time wears on, as their stomachs begin to growl at a delayed breakfast, Dima feels uneasy. He and Pasha, sitting on their stumps, keep looking around, over their shoulders, through the trees, seeing nothing more than other trees. When Dima suggests they eat something, Pasha yells that they will wait for Kolya, he will be back soon.

But Kolya does not appear, and Dima’s belly gets the better of him. He opens the biscuits and eats two before offering one to Pasha—Dima’s no fool, he doesn’t hold out the whole packet, knowing his friend’s temper might well make him dash them all in the dirt. He takes a single biscuit and pinches it delicately between the tips of his fingers, holds it up as one might a treat to a skittish animal.

Pasha accepts the biscuit after a moment’s consideration, crunches down on it as if it’s personally offended him. Dima hands over more; they eat until the wrapper’s empty even though they know they should be careful with their food. Eventually, without discussing it, they both rise and shoulder their packs. Pasha takes his small axe and cuts an arrow in the trunk of one the pine trees: This way. A message for Kolya in case he returns, more rabbit corpses in hand. Every ten trees, Pasha makes the same sign. He does it for hours—Dima is impressed, he doesn’t think he’d have the stamina, the belief, for that.

They walk and walk and walk. Sometimes Dima wonders if they’ll simply go in circles, come back to their own campsite, the last place they saw Kolya. Where he met the old woman. He does not tell Pasha about her, although part of him thinks he should. But he’s still raw from his friend’s mockery. He imagines the vitriol. You’re an idiot, Dima. Fucking bumpkin. Dreaming about old women. A path of stars, what the fuck is wrong with you?

A few hours later, they find Kolya.

It takes a few moments to figure out it’s him, however. There’s a pack on the ground not so far away, his rifle, his uniform, his greatcoat with the tear in the elbow where he caught it on a fence they climbed through three, no, four, days ago now.

The body hangs upside down from a tree in a clearing, skinless as a rabbit on a rotisserie, swaying a little in the breeze. There’s no drip-drip-drip of blood for that’s all poured out—dried up in a black sticky puddle in the dirt. There’s a buzzing, though. It’s winter. It’s so fucking cold. How can there be flies?

The young men rush to their friend, reaching, but there’s something about the corpse and its state, something about the lack of skin, the flies dancing on the meat of him, something about seeing every striation of muscle and tendon, and the eyes staring-staring-staring. The teeth without lips, so naked and so white. They don’t touch him, no. They can’t. They really can’t.

Up closer they realize there’s still a strip of hair on his head, a Mohawk stiff with red, in place of the golden locks of which he was so proud. They stare. They stare for a long time. Dima doesn’t know how long but he only knows that his brain hasn’t been working for a while—doesn’t kickstart again until Pasha moves. Steps away. Turns his back and walks onward as if their journey hadn’t been interrupted.

“We’re leaving him?” Dima asks and his voice is high. But he says “we.” We are. Not you.

Pasha swings about but instead of the expected ire, he’s calm, almost glacial. “Do you want to cut him down? Wrap him? Bury him? Do you want to touch him?”

Dima thinks about how Kolya will feel beneath Dima’s hands, without his skin, like those rabbits Dima peeled. Thinks about how, nearer, Kolya will smell even worse. All those flies. Thinks about how he will never get the stink from his nostrils or the memory of that most awful intimacy—that most naked of touches—from his mind.

Dima follows Pasha, doesn’t look back.

Eventually Pasha stops.

The sun is setting. They’ve found a stream and gratefully refilled their canteens. There’s a small campsite, too, although how long since it’s been used is anyone’s guess—spiders have built webs in the remains of the twigs and ashes. A day. A month. A year. More.

Dima gathers wood, starts a fire with the lighter his grandmother gave him when he first enlisted. Before she died. He shakes it, listens; not much left in the reservoir. He thinks Pasha has a lighter, too, but Kolya had matches. Waterproof matches, two boxes, in his pack. But they didn’t search his belongings, didn’t think to take something to aid in their own survival. Too late now. Too far to go back. He doesn’t mention it to Pasha.

There are no stumps here, so they sit cross-legged on the ground, in the pine needles. They pool their rations: three meals, two full canteens, no biscuits. They have to find their way out of here very soon. How much farther can it be? The place they were headed, the base they’re meant to blow up. Two hours through the woods, their commander had said, due west. Two hours, three days ago. Four? Turned around by fucking trees.

Pasha goes to sleep almost as soon as the day turns to dark, which it does with the swiftness of a light switch flicked. He mutters for Dima to wake him for his watch; but Dima’s unsure how he’s meant to count the hours. They are, he thinks, still crossing that two-hour corridor between then and now. Between the road where the truck dropped them off and the power station they were meant to destroy. Even if they find it, he muses, it won’t matter. Once again, the explosives are still in Kolya’s pack—he was the responsible one.

Dima almost speaks, almost wakes Pasha to tell him about the old woman. But before he can weigh up the wisdom of the decision, she’s there once again, across the fire from him. She in her khaki outfit, standing straight and tall like the trees, her hair loose silver.

“Good evening, Dima.”

“Good evening, Grandmother.”

“May I sit with you again?”

“Will it make a difference if I say no?”

She snorts. “None whatsoever, but I will think you impolite.”

“Me? I’m beneath notice. Nondescript.”

“Sometimes, Dima, that’s not a bad thing. To be able to pass beneath notice. To walk in the shadows. You might walk there forever.”

“Do you? Grandmother? Walk in the shadows?”

She smiles as if disappointed in him. Yet she gestures once again, just like the first night, last night. “And if I offer you this path again? A way home—what would you say? I should not do so, but there is something likeable about you, Dima.”

He looks at the path of stars, at the shiny points that dazzle his tired eyes. At its end—so near and yet so far!—he thinks he can see shadows moving against the windows, against the blinds. His mother, his sister, waiting for him to return. The warmth of the apartment that’s shabby but comfortable. It will smell like soup and fresh bread. His sister will be studying, his mother, too. The cats will be by the hearth, purring like small engines. Dima stares longingly, then looks at Pasha.

“But Pasha?” he says, and the old woman’s shaking her head even before he’s finishing speaking.

“On your own or not at all.”

“Why did you do that to Kolya?” he asks with a hitch in his voice, for he’s got no doubt it was her.

A pitying look, as if he should know. The old woman leans forward; the light from the flames makes of her a monstrosity, all shadow and furrows. But her expression isn’t unkind. Isn’t cruel. Just a little sad, a little resigned, as if she expected this, somehow. “Dima? Dima, my boy, you’re going to die. Out here. It’s so cold. So quiet and lonely.” She points at Pasha cocooned tight in his sleeping bag, oblivious. “Do you think he would hesitate one moment? Do you think he wouldn’t leave you behind?”

And Dima wants to cry. He thinks of Pasha fighting off Dima’s bullies when they were small and Dima was the smallest of them all. Yet he knows, too, that Pasha would leave him in a heartbeat if the old woman gave him this chance, but because Dima’s a coward he also knows he cannot do the same. If he runs now, he runs forever. He says, “I can’t.”

And the old woman is gone.

Dima thinks he must tell Pasha everything, no matter how angry he gets, no matter how much he mocks. Pasha must be warned for his own sake, so he can be alert.

But Dima can’t wake Pasha, not even when he yells and shouts and pushes the sleeping man. In the end he gives up. He swallows his fear, curls around it and his rifle, and tries to stay awake.

When dawn burns away the last of the dark and Dima wakes, it is to find that Pasha is missing.

Dima cries until snot runs from his nose and he can barely breathe for sobbing. Finally, though there’s nothing left, and he knows he can’t sit here by the merry little stream all day, can’t spend another night among the trees, he crawls over to Pasha’s pack—unlike Kolya’s it’s been left behind although he can’t say why—and ransacks it. He finds four extra ration packs his friend hadn’t admitted to. He claims them and Pasha’s lighter, the small axe, and Pasha’s canteen which he refills along with his own. He gathers his belongings, takes his bearings for all the good it does.

His first steps are stumbles into the stream, then across it, becoming surer and sturdier as he struggles up the bank. It feels as if he gains confidence from the certainty of his own footfalls, how his boots eat the earth. This way. Surely, yes, this way.

Dima continues for some time, in this fashion.

Until he begins to wonder if he’ll find Pasha somewhere in the woods, hanging from a branch like Kolya, turned into a meal for the insects and the crawling things of the day and night. Any foxes that might leap high enough to strip away some meat. He stops in his tracks, looks around, tries to establish where he is.

He has no idea.

Wait! There’s a sound! Water.

Dima runs towards it, his heart bursting with hope. There’s meant to be a stream where they should have come out, just across from the infrastructure they were meant to destroy.

He steps into the camp he departed this morning. There’s Pasha’s pack just as he left it, open, the contents disgorged. The cold ashes of the fire kicked over because the last thing he needed was to burn this forest down, or perhaps that’s exactly what he needs to do? But no, he won’t. Can’t.

Dima gathers more firewood, more and more and more until there’s a large pile of it, enough to last one final night, he thinks. He looks up. The sun’s falling. He breathes life into the tinder; when it’s crackling merrily, he sits in the dirt and waits for the old woman. At some point he sleeps and wakes only when she calls him gently by his name.

And this time he does what he’s avoided doing the past two nights: he looks properly at her feet. Without embarrassment—with fear, but not embarrassment. Shoeless, fur-covered, sharp-clawed, ridiculously long, rabbity from toe to hock. His mind had shied away the first and second times he saw it, from the memory blanked during the days. But there they are, now, undeniably giant rabbit’s feet. Nothing else about her is leporine. No ears, whiskers, or fluffy cotton tail. Just an old woman looking at him quizzically as if she’s not sure why he’s still alive.

“Will you share my fire, Grandmother?” he asks, voice a little raw from sleep as he sits up.

“Thank you, Dima.” She sits, elegantly, her legs folding beneath her, the scimitar curve of the toes dangerous in the firelight. “Have you worked it out yet?”

“Pasha is gone.”

“Yes.”

“Will I find him?”

She shakes her head and as she does her face shimmers: from old to middle-aged to young, so young. A girl, perhaps ten with silver eyes and silver hair, who opens her mouth—a tooth is missing, waiting for her adult ones to grow in—and says, “No. You won’t live long enough.”

Dima blinks.

The middle-aged woman repeats “Have you worked it out yet? Why?”

Dima blinks again, remembers back to that night. Thinks of the scrawny rabbits on the makeshift spit. He blinks yet again. Sees two bodies, impossibly large, not rabbits. Humans. Women. Old women. The smell of their cooking, the drip and sizzle of their fat, their gray hair shriveling in the heat, not catching fire but almost melting. Yes, melting.

“Your sisters?” he asks, swallows.

The old woman, his old woman, is back. “My friends.”

“Will you show me the path again, Grandmother?” Dima’s voice is so soft, yet it’s rich with hope. “I didn’t eat them.”

But she’s shaking her head, as he knew she would. “No, Dima. You had your chance—you had two chances, that’s one more than I should have given you. It’s too late now, my boy. My poor stupid boy. There are consequences for our actions—you must realize this.”

He nods. “I’m sorry, Grandmother, for what it’s worth.”

“I know.”

“Will you stay with me, Grandmother? Until it’s time.”

“Yes, Dima, I will remain.”

And they talk. They talk the whole length of the night. He tells her about his mother and sister and grandmother because he thinks it’s important that—at the end—he speaks of them. That their names are on his lips. She tells him the secrets of the forest—the magic, the spirits, the creatures that have watched his progress all these days and nights. When he asks if there was ever any chance for them, him and Pasha and Kolya, if they’d not committed murder in her woods, and she says, Perhaps. Perhaps she’d have forgiven them when it was merely trespass, but she hadn’t had to worry about that, had she? No, he says. They talk more and she tells him what she is, who she is, what she will be. She promises that she will tell his mother that he is gone, and he’s grateful, for he doesn’t like the idea of his family not knowing. He thinks about this witch with her faces and her feet taking the path of stars to his home, delivering a death note to his mother.

He thinks he is at peace with his demise. He thinks, right up until the sun begins to spear through the trees, that he will be calm. He’s wrong. Even before it’s light enough to see, he’s off like a shot, haring through the trunks, hurdling the stream and fallen branches. She doesn’t call after him. He hears no pursuit. But he knows she’s there.

She’s always going to be there.

When his breath runs out, when his hope—that ridiculous little flame—finally snuffs, then he slows. Dima jogs until he comes to a hole in the earth. A ditch, really, but it’s just his size. He looks behind, tries to find the trail he’s come from but there’s no sign he was ever there. No sign he was ever in this forest he should never have stepped into anyway. There’s only the glow, back there. A brilliant orange tinted with licks of red, turning the saplings, the old timber into silhouettes, then making them disappear as it gets closer and closer.

He knows he can’t outrun it—her. He didn’t want to come here, yet he did. And that little bit of blood from his grandmother, that red thread so slender that connects him to her and to this place? It’s too thin to keep him safe. Not enough. It won’t protect him. She tried to tell him, that old lady, in the cold hours, when she seemed, no, was. She was so kind, but he didn’t heed the kindness, and tried to tell him it was time to leave. Now, he’ll never get away.

He’s going to be here for a long time.

He’ll become part of the land.

Things will grow from him.

He’ll feed them, like the children he’ll never have.

There’s a comfort in that, he thinks; just a little.

He lies in the grave and watches the last morning stars, waits for the sky to fall.

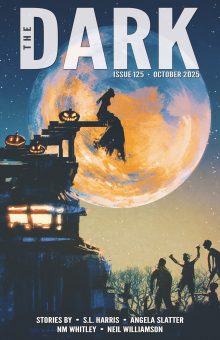

Originally published in The Book of Witches, edited by Jonathan Strahan.