For sale: one-of-a-kind secluded home in nice family neighborhood. private drive. inquire wilson realty, 432-6600.

Beatrice knew she would buy the house before she saw it, even before she knew the price. In a tough real estate market, people bought properties as-is, regardless of the home inspection report. They wanted entry into the cycle of homeownership. At fifty-five, she had nothing but her books and some money in the bank. She needed a home, a location she might call her own.

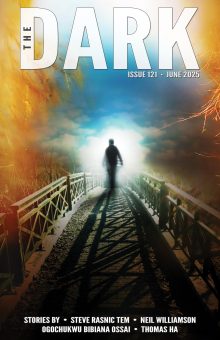

She thought it odd that the website provided no street view. The only photo was of a gate between two posts, with parallel fences enclosing a narrow lane receding into the distance. The number on the gate was “482.” The satellite view revealed a square lot in the middle of the block, accessible only from the long lane that pushed out toward the street like a tail. A brown roof was the only indication of a house.

The real estate agent, an older gentleman, picked her up for the viewing. She was unfamiliar with real estate language, but it seemed a strange way to put it. It was the same expression they used for funerals. The realtor’s outfit—a loud, checkered sports coat and matching tie—seemed inconsistent with his manner. He had the quiet voice and careful movements of a mortician. Beatrice encountered several of those in recent years, having lost her parents and both older sisters in a brief span of time. Though she hadn’t had much contact with them in recent years, she wasn’t yet used to the idea of being without a family. Some people can turn their friends into family. She didn’t have that talent.

He kept touching her hand, as if she needed comforting. She kept pulling away. If he persisted, she’d either scream or dig her nails into that so-serene face of his.

The agent started with small talk: the weather, her job, if she had plans for the weekend. She was no good at small talk. She felt uncomfortable sitting next to this overdressed man in his giant car. She answered using as few words as possible. “A young woman like you . . . ” Why did he call her young? Was this flattery? “You must enjoy your spare time. What do you?—”

“I read.” She had to stop this. “I read a lot. Tell me more about the property.”

He hesitated, perhaps put off by her abruptness. “There’s—much to like here. You’ll appreciate the unusual privacy this property offers.” He pulled his Cadillac sedan up to the gate. She wondered what it was about her that would lead him to say such a thing. But yes, it was like an island in the middle of the city. That was a large part of its appeal. She’d never been good with neighbors. There was nothing wrong with that, but it had its drawbacks.

“This entire property, including the driveway, is enclosed by an eight-foot-high security fence. Superior-quality engineered wood. It should last for decades.” He pressed the button on a remote control, and the gate swung open. The passage appeared much too narrow for his huge vehicle. She closed her eyes in anticipation of a scraping noise which never came.

The driveway seemed somehow longer than she expected, but the man drove so slowly that might have been the reason. There were only a few inches of clearance on either side. Good thing her own car was a subcompact.

The driveway ended in a concrete apron fronting the house. The realtor maneuvered carefully to keep his car on the pavement and off the lawn, which was startling in its vivid emerald color. She wondered how he was going to turn around when it came time to leave.

The house was small—a cottage. She wondered if it had a finished basement. Not that she needed or wanted one. She had few possessions. The house she grew up in had a basement, but she never went down there. It always flooded, and the air smelled poisonous.

The exterior was in great shape, covered with natural wood extending all the way to the ground, hiding the foundation. So much wood—it was beautiful. It looked grown in place rather than built. The window trim and door were painted deep blue.

“You can paint it if you like,” he said.

“Oh, I wouldn’t think of it.”

“Not everyone likes the rustic look.” He unlocked the door and led her inside. “The interior walls are something special, I think.” He laid a palm on the creamy surface. “Put your hand on the wall. I’ve never felt anything like it.” She did as he suggested. The wall was cool and so smooth. It wasn’t like plaster or stucco or anything she recognized. She pressed on it, and it gave a little beneath her hand. Not much, but still noticeable. “It’s—I don’t know—plant-ish,” he said. “Is that a word? Like a giant leaf or a flower petal. I’m told the original owner didn’t use a local builder. It must be a technique brought over from overseas.”

She could tell he was blathering about something he knew little about. It made him hard to listen to. “So, the owner is foreign?”

“No idea. I was hired by a go-between. I don’t have the owner’s name. It might not be an individual. It might be an investment company.”

Leaf or petal was a good analogy. If she looked at the walls from a few feet away, she could detect a subtle, overlapping pattern of ovoids. The workmanship—whatever the source—was incredible.

The floors in the six rooms were narrow wooden planks throughout, so polished they gleamed. The joints were so tight that the floor looked all of one piece. The realtor said, “I know it looks too perfect, but it’s all solid wood planks, not laminate.” The kitchen was small and basic, but Beatrice had never enjoyed cooking.

Of course, there was no furniture. Perfectly empty, she thought. She couldn’t imagine her shabby, hand-me-down furnishings in such a clean and pristine space.

“Are there other offers?”

“Surprisingly, no. Yours would be the first. If you agree to the price, it’s yours.” She felt relieved. It would be so disappointing if she had to fight for it. She wasn’t up for a fight. Now or ever.

As they were about to get back into his car, the realtor said, “I want to show you one more thing. This beautiful lawn.” He walked out into the middle of that small sea of blue-green and turned around. It seemed odd the way his shoes sank, then rose again on top of the luscious grass. “I think there’s some sort of underground irrigation system keeping it so healthy, but I can’t find the controls anywhere, so it looks like there’s nothing you have to do. It’s green year-round, and it never grows over three inches high, so you’ll never have to mow. Some sort of European variety, I believe. I need to ask the agency its name. I might want to plant some of this myself.”

Perhaps it was an optical illusion, but his shoes were sinking again. Soon she couldn’t see them at all, and the grass covered his ankles. “Come see!” he said.

Tiny things were rising out of the grass and floating around him. Thousands of them. She thought at first they might be gnats, or some other tiny insects. But as they struck his suit, they left tiny water stains. Droplets of water, but they were floating upward?

It was probably nothing. He seemed unconcerned, and she wasn’t used to life with a yard. She wasn’t buying the property for the grass, anyway. “No thanks. There’ll be plenty of time to watch the grass after I move in. Really, we need to go. I’ll sign whatever you like.” She climbed into the car and waited for him.

At work the following Friday, Carol was surprised Beatrice bought a house. “On your salary?” Carol was one of the assistant managers. Beatrice was in customer service, a much lower-paying job, but she didn’t mind. She had no desire to supervise or to run anything. She didn’t think she could and wouldn’t risk failure trying. What would be the point if she already knew she wouldn’t enjoy it?

She felt she needed to explain herself to Carol. “I’ve been saving for a very long time. And I’m not—I’m not getting any younger.”

“I see. None of us are, I guess.” Beatrice didn’t know how old Carol was, but believed she was younger. “Oh, that was rude of me, wasn’t it?”

“That’s okay.”

“No, me and my big mouth. Hey, now that you have a house, maybe you can catch yourself a man.”

“Maybe.” She tried to smile, but couldn’t quite manage it. How did Carol know she wasn’t dating? Of course, it was obvious. Beatrice didn’t know what she was lacking, but knew it was something. Carol probably knew the answer, but that wasn’t the sort of thing you asked somebody, especially if you were attracted to them.

“Beatrice, you’re so nice, aren’t you? You don’t really mind it when we’re rude to you, do you?” She saw Carol glancing at Bill sitting at his desk. Bill was laughing. The jerk. She hoped he choked on his own tongue. Carol was quite popular with the men in the office. Of course, who wouldn’t like Carol?

“You were just teasing. You meant nothing by it.” Beatrice could feel her face getting red. She hated that, and it happened all the time.

Carol put her arm around Beatrice’s shoulders, which made Beatrice’s face feel even hotter. She inhaled the full dosage of Carol’s perfume, notes of sweetness hovering over a deep, mossy smell. “How sweet you are,” Carol whispered, so close Beatrice could feel Carol’s moist breath on her face.

Then Carol went away to her desk in the back. Beatrice’s desk was at the front of the open office, where everybody could see her, but she couldn’t see anybody. The higher-ups—who had private offices by the windows—believed that facilitated open communication. She much preferred cubicle walls you could decorate. Here, she felt like the ugliest damn fish in the aquarium, the one that made the kids stop and stare.

Beatrice had all of next month to move in, but it only took her an afternoon. She examined all her furniture in her old apartment—most of it outdated pieces her parents used to own—and knew she didn’t want any of it in her new home. She would have a different life there, and she was afraid dragging too much of the old one into it would ruin the experience. She wasn’t fond of the pieces. Was that a terrible thing to admit?

She packed her clothing and most of her books, her dishes and kitchen utensils, two bags of groceries, and a few knickknacks. It was hardly enough to fill a quarter of the moving van she’d hired. She left all the furniture, the wall hangings, even the framed photographs. She wrote a highly apologetic note to her landlord, stating he was welcome to her damage deposit, and attached an additional check to cover his inconvenience, and drove away with the moving guys following in their van. She had an old sleeping bag in the trunk of her car. She would use that until she could afford a new bed. She could eat at the kitchen counter or picnic-style on the floor. She’d depleted her savings. She imagined she would furnish her new home one considered piece at a time. Everything needed to be perfect there.

She opened the gate and drove her little car up the drive, the men in their moving van creeping behind. She warned them about the narrow drive, and they looked none too happy about it. If they gave her trouble, she wouldn’t tip them. They parked close to the edge of the apron, almost on the grass. She rushed over before they got out. “Could you park behind me? The grass . . . I just don’t want you stepping on the grass. It’s . . . delicate.”

The men nodded. Maybe they weren’t used to a mousy, little woman speaking up. It only took them a few minutes to unload everything into her living room. Without furniture, she only had the kitchen things to put away in the cabinets and drawers. Even though they had done little, she gave them a generous tip, despite what she suspected about their attitude. They couldn’t turn around, so she watched them back down the drive. A button by her front door allowed her to open and close the gate.

Those first few days in Beatrice’s new house were heavenly. Despite sleeping on a hardwood floor, she slept well, waking when the sun rose above the bottom edge of her front window, which gave her just enough time to shower, dress, and head to the office. She was rarely hungry for breakfast, but if she was, there were always the office donuts and coffee.

She lost weight. Carol noticed, and when she pointed it out, Beatrice couldn’t control a huge grin. Dinner at home was usually a veggie salad. She bought a lawn chair, which she placed outside by the front door, and that’s where she usually ate, enjoying the sun on her face and the rich, moist smell of the grass, which—like the realtor promised—flourished without watering.

She couldn’t see anything of the neighborhood above the top of her fence, including tall nearby buildings which should have been visible. But the cerulean sky was view enough for her, the passing clouds like tall sailboats on an endless sea.

She wondered how she’d gotten so lucky, acquiring this place so easily, and why there had been no other offers. The fence might have something to do with it. Not everyone craved that much privacy. Or that lawn. As beautiful as its color was, and as low-maintenance as it was, she was reluctant to walk on it, and so she didn’t. She wasn’t sure why—maybe she didn’t want to spoil its perfection. Still, it was nice having something of nature to contemplate. On hot days, as the sun went down the air above the lawn appeared to shimmer, and distortions would appear, the air warping. The phenomenon was puzzling but pleasant to watch. Sometimes, she fell asleep in the chair, not waking until the next morning, the sun in her eyes and her body dripping with sweat. Those days, she had to rush to shower and get to work on time. Sometimes, she was late. It was embarrassing. She’d never done that before. She wasn’t that well-liked—would she get fired? It seemed a distinct possibility.

One morning, late again, Beatrice came to work with her hair wrapped in a towel. She didn’t realize until she felt it slipping. She ran into the bathroom and threw the towel into the trash. When she came out, Carol was standing by her desk, looking through some papers. Beatrice could feel damp strands of hair plastered to the back of her neck, but it was too late to do anything about it.

“Beatrice? I never figured you for the walk of shame,” Carol said with a chuckle. Someone else laughed, but she was too embarrassed to look around and see who.

“No, no. I—I’m not seeing anyone, I swear. I overslept. I’m sorry. This is bad, isn’t it?”

“Oh, you’re just a terrible employee. I don’t mean that. I’m late sometimes, but you, you’re never late. Hot date last night?”

“No, I told you. I overslept.”

“Yes, you said that. But your hair’s wet. You didn’t go swimming, did you?”

“Of course not.” But she didn’t remember taking a shower. So, why was her hair wet?

“Come back into the lady’s room with me. I’ll fix you up.”

Carol grabbed a bag from under her desk and led Beatrice into the bathroom. The bag contained a hair dryer, brush, cosmetics, and towels. “You keep all this here?”

“And a change of clothes. Women have to be prepared. We’re not like guys.” Without asking, Carol put a fresh towel around Beatrice’s shoulders, retrieved the brush and dryer, and began blow-drying Beatrice’s hair. “I’ve been meaning to talk to you about your hair. It looks much better down. Trust me. You’ll like it, or at least the guys will.”

“I don’t care what they—” It felt wonderful, the way Carol brushed her hair. Beatrice couldn’t remember the last time anyone took care of her like that. Her mother tried when she was little, but her mother pulled too hard. After a while, Beatrice wouldn’t let her mother anywhere near her with a brush.

Carol was gentle. And she hummed. The humming was soothing. Beatrice kept watching Carol in the mirror, but tried to look away if she thought Carol might notice. She’d always thought Carol used too much makeup, and her lipstick was too red. But there was also something beautiful and a little brave about it.

“How’s the new place?”

She couldn’t think of the right words. It was clean. It was well lit. And it was mostly empty, but she didn’t want to tell Carol that. “It’s where I belong,” she replied.

“Well, that’s good, I guess.” Beatrice could see Carol’s tiny frown in the mirror, but she didn’t know what it meant.

It was a small office, and the desks were close together. She often heard whispering and giggling, and because none of those whispered conversations included her, she suspected they might be about her, but of course, she couldn’t know for sure. Many of these conversations took place around Bill’s desk back in the corner. Bill and Carol were friends, so why didn’t she make him stop? Unless she was in on the joke.

Bill didn’t supervise Beatrice, but he was the one who routed the customer service calls. Beatrice got the worst ones—the rude, the incoherent, the threatening. She almost never talked to normal customers with normal problems. That couldn’t have been accidental; she was sure. She could hear Bill laughing behind her when she was on particularly tough calls. The snickering and whispering came from other parts of the office as well, as other coworkers were clued in to the joke. That was the problem with having one of the desks near the front—you couldn’t see what was going on behind your back. She supposed she could turn her chair around and stare at them, but she could never be that bold. She asked several times if she could move, but HR said it was an inopportune time. Maybe when they got a bigger office. She’d worked there eight years, and they never got that big office.

A few minutes after she left the restroom, her desk phone rang. The person on the other end was shouting even before she got the receiver all the way to her ear.

“Are you the same bitch I talked to last time?”

“Sir, I don’t—”

“Of course you are. Let me speak to your manager.” Company policy was that she wasn’t supposed to kick a phone call to a higher-up unless she’d been on the phone with the customer for at least five minutes.

“Sir, could we start with you describing the problem?”

“My shipment still hasn’t arrived! That’s my fucking problem!”

“Could you give me your order number?”

“You have my order number! Last year, one of my packages went to goddamn Canada!”

“Sir, please. Don’t talk to me like that.”

“You’re worthless! I’m going to come down there and slap you!”

Beatrice’s hand shook so badly she almost dropped the phone. Then she heard the explosive laughter behind her. It was the rest of the office, including Carol. Bill came out of the coat closet, waving his cell phone. “Fucking Canada!” he shouted. It was the voice on the phone. She closed her eyes. Where was her letter opener? She imagined killing him with it.

She called in sick the next day, and the day after that. Then she forgot a day and didn’t call. Then another. The office called several times. She stared at the number on Caller ID, but didn’t pick up. She couldn’t afford to lose this job. She’d paid for the house in full, but there was insurance, taxes, utilities, food, and she was still without furniture. She had a credit card, but if she were to charge something, she would need to make the payments. She needed an income, sooner rather than later. But she couldn’t imagine going back there. The worst thing was seeing Carol laughing it up with the rest of them.

She spent her days sitting in the chair by the door, watching the lawn. She never imagined there would be so much to see—it was just a square of short grass. No flowers, bushes, or trees. No rocks or ornamentation, no structures of any kind. But a few days’ observation revealed a lot going on.

Insects visited. She was only aware of the flying ones—the butterflies, moths, mosquitoes, bees, and other winged things she had no names for. Landing, taking off, never stopping for more than a few seconds. Because of the lack of flowers, she wondered what attracted them. Birds flew overhead, but never landed, which seemed odd. Didn’t birds eat insects? No stray cats, either. Maybe because of the fence.

The air above the grass shimmered with heat and sometimes, with moisture. Sometimes there was cloudiness, localized weather. This, too, seemed odd to her. It hadn’t rained in some time. The realtor talked about some sort of hidden irrigation system, but she saw no evidence of it. She hadn’t received her first water bill—would it be an unpleasant surprise?

Sometimes, she saw shapes in the clouds above the lawn. Vague impressions, reflections. Mirages perhaps? She saw tall, exotic plants and nude women dancing. It was embarrassing. She couldn’t figure out why she would imagine such things.

A gray squirrel leaped from the top of the nearest fence. Now, this was something new and unexpected. Beatrice must have been bored because she couldn’t take her eyes off it. She watched as it scurried across the pavement, peering at the grass but never going onto it, racing down the driveway toward the gate but always coming back. She thought about going inside to get it something to eat, but she didn’t want to miss any of its antics.

The squirrel saw something in the grass, and it leaped several feet into the center of the yard. It looked down, turned, and stared at her as if noticing her for the first time. It sank, its front paws clawing at the grass, but in seconds only its head and one paw were visible above ground, and then it disappeared.

Was there some sort of hole in her yard? She jumped out of her chair and ran across the grass to where the squirrel disappeared. It took her a few seconds to realize her feet were sinking into the grass before she screamed. She was up to her knees, and then her waist, everything numbing as it vanished. Her head went under as she clutched the turf, trying to remain above ground. There was nothing underneath to support her.

Beatrice closed her mouth and held her breath. She kept her eyes open. She was underwater, inside a glowing blue sea, growing darker as she descended. Above her, she could still see a haze of sunlight and a green fuzziness she assumed was the grass on the surface. But the grass was fading. She kicked her feet, and they provided some maneuverability, but not enough to keep her from sinking further.

She could feel her long brown hair—she hadn’t worn it up since that day Carol worked on it—floating around her face. She kept brushing it away with her hand so she could see. As she dropped an abundance of brownish plants drifted around her—some variety of seaweed with a root-like base and undulating fronds around a central stem. Someone whispered sargassum into her ear, so cool and gentle it thrilled. She didn’t know the word, and twisting her head around, she couldn’t find the speaker.

She saw the sea floor beneath her—there were creatures swimming around, not all of them fish. Some were transparent. Some were large and amorphous-looking. Some regions of the water were much darker than others, and although she could make out no details, they filled her with anxiety.

She brushed against what she thought was a broad cliff, but when she touched it, it felt woody. She followed it upward with her eyes and could see the outline of her house, fixed to the top of this giant trunk like some kind of bloom.

Something swam past her. She turned and saw the swimmer and tried to find some place along the trunk where she might hide. A nude woman with dark green skin and instead of legs, a long and sinuous fish tail. Beatrice moved to follow the woman and was disappointed when she disappeared into the shadows. Beatrice tried to swim there, but became tangled up in the seaweed and couldn’t move. She panicked and tried to scream, but no sound came out of her mouth. She realized then she had been breathing underwater all this time.

She struggled, then felt her bonds loosen. The woman was behind her, pulling the seaweed apart. Beatrice could see the woman’s hair—more like vegetation than hair, woven of branches and barbs. Beatrice reached out, wanting to touch the swimmer’s bare skin, when the woman opened her mouth impossibly wide to reveal long, needle-like teeth, the squirrel carcass trapped behind them as if in a cage.

She woke up lying on the hot pavement by her chair. She was damp, her clothing stuck to her skin, but the sun was so hot overhead, maybe she’d passed out from the heat and sweat through her clothes. Her cellphone lay by her side, ringing. She rolled over and looked at the screen. It was Carol. Her breath caught, and she answered.

“Beatrice? Finally!”

“I’m sorry. I know I should have called. Have they fired me?”

“No, no. I told them you’ve been calling me every day. That you’ve been deathly ill. They’ve talked about sending flowers.”

“Why, why would you do that?”

“I owe you, Honey.” No one had ever called her Honey before, not even her mother. “I’m so sorry. I shouldn’t have laughed at that stupid prank. It was just—I don’t know—it caught me off-guard. I swear. I’ll—we’ll make it up to you.”

Carol sounded as if she meant it, but Beatrice had been fooled before. “How would you do that?”

“We’ll throw you a housewarming party. You didn’t have one, did you? At least you didn’t invite anyone from the office.”

“I—”

“It doesn’t matter. We’ll bring the food to your place—everything. How about this Saturday, one o’clock? Just make yourself pretty, okay?”

“Well, sure. Sure, that would be nice.”

“It’s a done deal. Gotta go. See you then!”

Carol kept saying we. Beatrice wondered who that included. Hopefully not Bill.

After Carol’s phone call, Beatrice remembered she had no furniture. That would not work at all. But she still had her job, so it was safe to use her credit card.

She changed clothes and drove to a Danish furniture store, thinking that style would fit her home. She arranged for Friday delivery of a credenza, dining table and chairs, bedroom suite, coffee table, couch, and several side chairs. At another store, she bought a selection of outdoor furniture and a flat-screen TV. Beatrice didn’t watch TV, but she figured it would look strange to them if she didn’t have one. Hopefully, no one would try to turn the thing on. She could send it back after the party.

All this cost a fortune, and she would only have twenty-four hours to set it up. She hoped she hadn’t bought herself a huge problem, but she would worry about that later.

Saturday, she was arranging the last of the chairs when her coworkers showed up in three cars. She ran out to make sure they didn’t park on the grass.

Bill drove one of the cars, and of course, he was the one trying to park too close to the lawn. She ran in front of his car and waved him away. He jumped out. “Jesus! I could’ve killed you!”

“Sorry, sorry. But it’s—a new lawn. It’s delicate.”

“Particular, aren’t you? I wasn’t—” Carol grabbed his arm, interrupting him. So, she was riding with him. Were they dating?

“Hi Beatrice! Where do you want the food? Robert brought a grill we can set up in the driveway.” Carol wore a bright yellow sundress. She’d toned down her makeup. She looked beautiful. The guys were dressed almost identically in colorful T-shirts, shorts, and sandals. Beatrice thought they looked goofy.

She expected each of them to come to her and apologize. It didn’t happen. Carol was the only one who ever said she was sorry. They had their little weekend party. They just used her place as a location. She should never have predicted kindness.

They grilled hot dogs and hamburgers. There were plenty of chips and fruit and cases of beer, which Beatrice didn’t care for, but she guessed that for most people a party meant alcohol. They only went inside the house to use the bathroom. Carol said, “Everything looks nice.” No one else even feigned interest.

One guy brought a red Frisbee. He kept throwing it straight up in the air, then catching it in fanciful ways—behind his back, low to the ground, high overhead. Sometimes he missed, and it bounced and rolled like a coin on edge. Every time it got close to the grass, she could feel her breath seize, but it always veered away.

Then Bill started running, shouting over his shoulder, “I’m going for a long pass!” He went straight for the lawn, crossed it, and caught the Frisbee at the far side of the yard. Beatrice thought she would faint, but he stood there grinning, holding the Frisbee up like a trophy. Perhaps taking that as an invitation, the other guys—Robert, John, the fellow who brought the Frisbee who she didn’t know—ran out onto the grass to make a large square.

“No, don’t! Don’t!” she shouted. The guys were laughing and didn’t hear her.

Carol came up to her, wobbly from drinking, and said “Lighten up, girl. You’ll never make friends with that attitude.” Carol staggered into the yard. “Throw it to me!”

Beatrice tried to grab her by the arm and drag her back, but Carol shook her off. “Let go of me!”

Carol stumbled into the middle of the yard and plopped down. The others started laughing. Then they all disappeared, too quickly for a yell or struggle.

Beatrice gasped, then raced to the spot where she last saw Carol.

This time the world under appeared darker and far more extensive than on Beatrice’s last venture. She looked for Carol—frankly, she didn’t care what happened to the others—but could see her nowhere. Much more of that seaweed was in evidence, endless strands of it reaching from the surface to the hidden bottom below. An enormous mass of it had clumped together into a small planet which floated nearby. The liquid itself—it no longer felt accurate to call it water—seemed thicker, syrupier. She could feel it dripping and sliding across her skin like oil.

She caught frantic activity out of the corner of her eye, and she swam in that direction. Her swimming technique had improved, she thought. She’d never been a skilled swimmer, but now her body followed her eyes without hesitation. She was all one intentional movement. Her kicking, the undulations of her torso, her arms, all worked in sequence to propel her forward.

It was the guys, all four of them. They’d lost their clothing and were naked, their dangly bits bobbing like shaved squirrels. But what she at first interpreted as panic turned out to be childish play. They were grabbing at each other, twisting, and shaking their asses, their mouths wide in glee, thrilled by their new ability to breathe underwater. Bill looked especially enraptured.

It annoyed her. In part because this was a dark and scary place. They were drowning for god’s sake. But it was all a game to them. These were not serious people. And worse, Carol was nowhere to be seen. Had they even bothered to look for her?

Beatrice turned away from these boys and went deeper. Something yellow drifted out of the miasma of oily liquid and disintegrating vegetation. Like a blooming flower or a new sun.

Carol had her back turned, her dress billowing and warping like some exotic deep-sea anemone, providing immodest peeks at her legs, her thighs. Her shoulders were slumped, her head bowed. Fearing the worst, Beatrice swam in front of her, stretched out a hand and shook her shoulder.

Carol raised her head and her eyes went wide. She opened her mouth and screamed an explosion of bubbles, then with a flurry of awkward arm sweeps and kicks tried to rise toward the surface. She’s trying to get away from me, Beatrice thought. Her friend was panicking. She didn’t know what she was doing. Beatrice went after her, soon overtaking her. She tried to grab her arm, hoping to pull her into an embrace and calm her down. But Carol was distraught, kicking, squirming away, again screaming bubbles.

Although they were both rising toward the surface, into the sunlight zone, the world suddenly became dark again. Beatrice looked up and saw the green woman with the long fish tail, or one like her, because there were dozens of her now, almost identical, swarming the upper regions of sea, surrounding those goofy boys, goofy no longer, as they were being eaten. The green fish women were tearing them apart, then devouring the pieces.

She stared at Carol, who was still screaming, and let her go. She hoped Carol would be okay, although under the circumstances it was hard to say in which direction safety lay. At least the fish women were ignoring her.

For a moment, watching Carol’s bare legs scissoring into the distance, Beatrice felt an urge to go after her. She didn’t understand what she was feeling. Loss maybe? Resentment? But she couldn’t stop smiling. She raised her fingers to feel the extent of her grin, and all those terrible, sharp teeth filling her mouth.