“Awa, did you see this?”

My sister is holding out her phone for me to read. There are streaks of brown henna, which she has been trying to apply in preparation for a friend’s wedding, on the cracked screen. Kana refused my help, saying my hands were too clumsy for the intricate, precise patterns she wanted tattooed, so I’m sitting with her in the living room watching her mess it up.

It is dusk. Orange light washes over our faces and our shabby polyester couches that sport too many holes for us to fix now. The orange is too saturated, disfiguring Kana’s facial features—like when you stare at your face in the mirror for too long and the image staring back is not yours anymore. It bounces off a couple of photographs hung on the wall: her gap-toothed smile as she receives prizes on the last day of elementary school, my parents on their wedding day with expressions too stern for what should be their big day. I notice again how there is no picture of me.

My palms are sweaty as I fish the phone from her hands. The hour brings in a heat that seems to entrap you in its own currents. It stays into the night, as if it crawled under your skin before bringing it to a boiling point.

Despite wearing my glasses, I squint. It’s a social media post, with the user asking, “Did you hear about that lost kid that stops you in traffic or the sidewalk, asking that you help him find his mother? Then he takes you to a place where there’s a woman with donkey legs, and you disappear afterwards?”

“I haven’t,” I mumble, taken aback.

“People create all sorts of silly stories to bring the supernatural into everything.” A tiny laugh bursts from her lips. “Djinnés, demons, maneaters, all because they can’t face the truth of how wicked humans are. They’re the ones kidnapping people, stealing, and raging terror everywhere.”

She positions the back of her head to rest against my shoulder, then stares through the window, absently. I don’t tell her what I think of that post and her rant, because something other than the heat creeps into me. A sense of unease, doom even, that clings to my pores and accelerates my heartbeat. I try waving it away, telling myself that it’s just a story. I open my mouth, even, intending to laugh at how ridiculous the post sounds. I want to agree with her that men wear the guise of demons to commit human acts, but my throat is twisted about itself and I cannot utter a word.

“Be careful rek, little sis,” Kana says as she turns back to me with a crooked smile. Hot wind slithers in from the open window. I know Mom will scold me for not shutting it before Timis—the time when boundaries grow thin between our world and the obscure, when all sorts of evil things try to worm themselves into people’s houses.

The Adhan rings from the nearby mosque, in a firm yet emotional voice, and the spell is broken. I can breathe again. My sister doesn’t notice, talking over the voice for a brief moment. “With that distracted head of yours, you might get snatched, too!”

Kana disappears a week later. Our world is torn apart as we look for her everywhere, not caring to sleep or to eat. All our time is spent printing posters and sharing posters online, and harassing people to look at the posters and tell us if they’ve seen her anywhere. It’s not the picture of her ten-year-old self hanging in our living room: this one I snapped a year ago while she sat on a bench outside, unsmiling, in a white blouse and Kokodunda pants that were too big for her. Kana hated this photo.

My father’s eyes remain gaunt as he scours the streets of Dakar in his arthritic Renault. He braves traffic jams, careless moto drivers, and September rainstorms to find his favorite daughter. My mother keeps crying, silently, and I’m not the one she wants comfort from.

A week becomes two, then three. I come home from another round of solo searching, even though I’m supposed to be back in school, to find my parents slouched in the same couch Kana did her henna in. Both in tears, they are inches apart, as if not allowing themselves comfort from each other. Grieving their daughter separately, as if she’s been sliced in two and they each clung to different parts of her for dear life.

“What happened?” I ask, horrified. Did they find her?

Is she dead?

“A man called,” Mom says, wiping tears and snot off her elongated face without looking straight at me. She’s thinner than she ever was before, disappearing in the folds of her white meulfeu. “Saying he knew where Kana was, but to send him cab money so he could come here and give us all the details. That the people responsible for Kana’s disappearance tapped his phone and it would be safer to talk in person.”

Mom sniffles, looking over my head as if I’m absent and she is talking to herself, “Your father sent 10k on his number. Now he’s blocked us after refusing to take our calls.”

Rage fills me with an intensity I have never felt before. How could someone take advantage of a distressed family in a time like this? How could my father, the most leveled-head person I know, let himself be scammed?

I see red. I bolt out of the house before the call for the Timis prayer, ignoring the pit of hunger in my stomach and the exhaustion clogging my joints.

My parents don’t call after me.

I walk, and walk, imbued with a sense of abandonment and rage that has nowhere to go. I can only hear the blood roaring in my ears. I search through the streets of Maristes like a madwoman, my lips dry and my sandaled feet covered in dust. Resolve fills me again in the middle of my erratic state, and I think of one last place to go. It is a dangerous, impossible idea. It is all I have.

This time, the Adhan finds me under the bridge that links Cambérène to the entrance of Maristes. I pace from one end of the darkening tunnel to another, time and time again, oblivious to the vendor’s stares as they pull away from me, or the pompous people in their luxurious cars. They, at least, will be going home to their families. Mine was left fractured, in the blink of an eye, the gaping hole left by my sister’s disappearance threatening to devour us whole.

Kana was the only one that saw me, through that idealistic, frivolous gaze of hers. I was content listening to her blabbering about the tiniest details in her life. Friends, sour-eyed professors, crude university boys. She would tell me everything as her head rested on my shoulder, satisfied with my silent attention. I would rather risk everything than return to the empty house. To my parents, indifferent to each other and to me, when they weren’t staring at my shadow and wondering why I hadn’t been taken in her stead.

No sooner had my brain wrapped around that feeling than he appears. The boy, at my left side. Crimson and vivid orange illuminate his plain, unreadable features. At first glance, you could mistake him for a talibé. His clothes, however, aren’t dirty, or torn. There is no empty plastic container under his arm, to receive money or meals. First, he stares at the masses trickling down on either side of us as they scurry to the nearby mosque before the end of the first raka’ah. His skin is ashy, his eyes darker than the bottom of a well when he finally looks into mine.

There’s no “can you help me find my family? I’m lost.” No staged tears, or pretense of being exhausted and hungry. I want to follow him to where all things are lost. Taken, by whoever he’s servicing.

The boy begins to walk toward the middle of the shady path illuminated by car lights, with a dirty and rough brick surface. I follow as the unease I felt weeks ago returns, gnawing at my bones. Like a mirage, the segment of the wall he lays his forehead against begins to shimmer.

A chill races up my spine as his fingers grasp mine. There’s such a cacophony all around us, of buses and smoke and vociferous calls from the street vendors, yet I feel, like wetness under my skin, the moment we disappear under their eyes. He smiles, then, a gaping smile with no teeth. The second before he pulls me into the melting red, I glimpse prints of hooves on the dusty side walk.

I cannot open my eyes as we move through warm wetness, crossing into someplace that isn’t our world. Somehow, it is tangible. It lasts three seconds before the motion stops, and I sense my feet resting on stony ground. Cars race way above us. My eyes only see darkness when I pry them open, the boy’s breath scalding against the skin of my arm.

With strange certainty, I realize we are deep into the discarded tunnels whose entries punctuate the Cheikh Anta Diop avenue. They’re littered with trash and stale water, which I can taste at the back of my throat. Homeless people sometimes occupy them, shivering with hunger from under dirty rags. How strange, or desperate, they must be to seek refuge in such places.

As desperate as I am, surely.

His face pressed against my arm, the boy nudges me downward. At times, the tunnel narrows against our bodies, pressing my arms against my flanks until they’re sore. It feels like we’re being digested inside the bowels of an enormous creature. My skin is raw, oversensitized every time the dampness of the walls brush against it. It feels like my chest is being squeezed by unseen forces.

“Where are you taking me?” I croak, but my question fades away, ignored. I lose sense of up and down, my fists clenched around the fabric of my sweatpants. Refusing, above all, to surrender to the terror that looms over me when a clatter of hooves rises from behind us. The inability for me to discern who, what follows us drives me crazy. It is only then, as our breaths grow louder from the sustained effort, that I take in the weight of what I got myself into.

Nothing about this was natural. I threw myself, willingly, into the maw of something obscure. I silenced my instincts when they kept telling me this was worse than suicide. Was my sister even alive, still? What of our fate, if I failed to get us away from there?

Tears sting the corners of my eyes as the noises grow more intense. Grunts, light snickers, growls. Worse, the boy seems oblivious to it all, always pushing me forward, clinging to me like a parasite. I begin to doubt if he’s human at all, and that alone traps the breath in my body. Infinitely, I’m sinking in darkness, and I’m alone. The smells, rank and prickling, assault my nostrils. Underneath it all is the coppery scent of blood.

We begin to ascend, slightly, and hints of light flutter ahead. My glasses lost somewhere along the way, I squint my eyes to try and make sense of it. Have we reached the end? Will we resurface into the falling night, from the mouth of a regular tunnel entry? Perhaps this was a walking nightmare, brought forth by fatigue and lack of sleep. I lick my lips, desperation morphing into confusion.

But the lights only grow harsher, hurting my eyes. Waves of heat increasingly thrash against me, and my resolve weakens. My breath wheezes free of my throat as I force myself not to look back. The creatures have crawled closer, an unnatural escort that I prefer held in darkness. I feel them breathing down my neck. I do not trust myself not to die of terror, right there and then, at their sight in bright light.

With no transition, we emerge in an open desert.

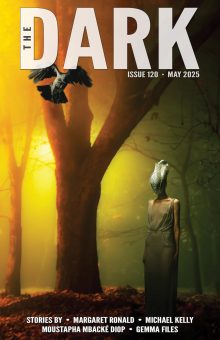

Winds twirl all around us, as if possessing a mind of their own. Kana would say, in a tone heavy with the mockery known to nonbelievers, that winds like these are hidden djinnés in movement. The grains of sand they carry lodge themselves in my eyes. Only when they are cleared do I realize that this is no ordinary desert: the sky is a saturated, bloody red, empty of anything celestial; the sand is black, with a gritty consistency as I roll it under my toes.

I turn to look at the boy first, and he’s looking back at me with an apathetic gaze that twists my insides. Somehow, I find my voice again. “My sister, I’m looking for her. Kana. She’s tall. There’s old henna on her hands, maybe. The back of her neck has a nasty burn from a haircare incident. She’s . . . She doesn’t like it when it’s visible but the shirt she was wearing when she disappeared has a wide collar so . . . I don’t know, you must have seen her. Taken her to the woman with . . . Please, tell me—”

Not above a whisper, my voice trails off as the boy smiles for a second time. The unsettling winds have stopped. And I see the trees.

They are distributed erratically all around us. Naked, gnarled branches spread from odd-shaped trunks. With great effort, I’m dragging my feet toward one of them. I raise my hand tentatively to meet the deep red bark, tracing its swirls with my fingers—it’s like the contours of a face are imprinted in it, sunken in desperation. There’s a faint, pulsating beat under the roughness. Sobs build from inside my chest as I look frantically around, my eyes wide open.

All of them.

All of them are shaped like bodies with arms wide and carved faces: they’re contorted in different expressions of great terror and pain. I sense my own heartbeat threatening to bubble off my lips and the beginning of a scream that once freed, might never stop. All these bodies, frozen in vegetal. Tortured. Was my sister one of them?

Fueled by the last of my energy, I’m sprinting from tree to tree. I’m touching, scrutinizing every face to seek the one that belongs to Kana. There are too many of them . . .

“She’s waiting for you.”

The boy’s voice, seemingly regular for a seven-year-old, startles me. He has appeared behind me, wearing an indecipherable look on his face. I make an abstraction of the fact that it’s the first time he addresses me directly; my pulse races faster, because I know it’s not Kana he’s referring to.

Her. The woman he services, somehow. The one with donkey legs.

A lump of hardened saliva clogs my throat. “Take me to her,” I manage.

He smiles, one last time. When I blink, bile rises up my throat and everything shifts again.

I am now inside a cave, alone. Walls of a rock sheening with red surround me. Sweat drenches the back of my shirt—here, it feels like the inside of a volcano. Acrid sulfur permeates the air as I find it harder to breathe. I’m heaving, coughing, looking around for a way out of this place, when my eyes land on the woman.

She sits atop a throne of bones: jagged, pale things that aren’t human-looking. Her pale brown skin stops at her waist, from where a pair of sinewy legs are covered in black, shiny fur. When she stands and walks toward me, her feet clop against the rocky ground.

My entire body is frozen in place. The sulfuric fumes are stronger around her body. Her chest is bare, with small breasts that perk upward and away from each other. She sets sepulchral, white eyes on me as she stops, inches away. A mix of repulsion and fascination overtakes me when I see the fat black worms emerging from her scalp in a slimy pattern that resembles braids.

“You are here for your sister,” she slurs, and her voice is as soft, as unnervingly normal as the boy. At first, I cannot reply. My terror is too loud, filling the silence between us. I know my eyes appear wild and haunted: I am prey, immobilized in front of a supreme predator. She is no woman, no djinné, no maneater. I don’t know what she is. I nod.

“I can deliver her back to you. Unharmed.” She smiles, streaks of blood staining her teeth. Whose blood is it? My head swirls at the possibilities. “Would you like to have her back, Awa?”

No ayah, no word of protection is left in my memory: I have forgotten it all. I am in Jahannam. I nod, again.

“But first, my darling, you must eat.”

She produces a fruit from behind her. Unlike nothing I’ve ever seen before, it is oblong and juicy, with a thin, wine-colored skin covering it. It’s heavy between my fingers as she passes it on to me. Its sticky, sweet smell worsens my dizziness as I lift it close to my mouth. Wetness coats my skin where I’m holding it; I think it’s dew, first, but up close, it has an unmistakable coppery scent.

I am so thirsty. My insides scream for sustenance. I feel the weight of her gaze upon me as I tremble, my breath thinner than ever.

She’ll let me save Kana. I can take her back to our parents. We could be a family again, even if that idea of family seemed to never include me.

I bite into the fruit.

I like to convince myself that I don’t remember what happened down there, with the trees and the woman. I keep silent, even when Kana and I are found, unscathed, under the bridge one morning. I don’t even remember reuniting with my sister, but my hand is tight around hers and she refuses to let go. She’s not changed since we last saw her, but I avoid her eyes. I’m afraid of what she could see in mine.

Police investigators try to interrogate us, to no avail. They’re eager to close yet another missing person case, or perhaps the traces of old blood they pretend not to smell in my breath makes them queasy. When we’re taken back to our parents, my mother sobs so hard that her asthmatic lungs must be left bruised. They embrace us both; I was missing for only one night, though it seemed like decades have passed in the cursed underworld. Surrounded by their warmth, I let tears slide off my eyes and hug them back. We had, after all, the chance of building a decent family relationship now.

Then night comes, and all truths burst forward. I remember how tangy the fruit tasted, the burning unleashed in my insides, the retches and bleeding eyes afterward. I took more bites from it, and vomited, and ate again as the fruit seemed to never finish. I remember how the woman guided my hand as I carved in the wood with a ruby dagger, ignoring the dark blood oozing from peeled flesh underneath. Standing before a brazier, lights flickering off the sweat on my face as the damned screamed in agony and burned. I fed the fire with my own two hands, with pieces of wood that still pulsated. I grinned as all hope of those people ever getting back to their families went up in screeching flames and—

It went like this, night after night. Guilt keeps me awake; silence becomes my companion. My sister doesn’t talk much either, but she’s always touching me: my neck, my face, my left arm where a jagged, erythematous mark is now imprinted. She notices when my body hair grows coarser over my legs. I don’t tell her when the first cramps and the first blood mark imminent change in my body—Kana knows, either way.

Joining my family for meals, where my mother extracts laughter out of her throat even though she’s never been a joyous person, becomes impossible. Since they don’t understand how otherness has taken over my body, they begin to push me away, as they always did before. It makes it all easier, because I can sense immobility settling in the muscles of my feet, strengthening the keratin bonds over my skin.

Another transformation is near.

It scares me, how the guilt starts to fade away, along with my humanity. I surrender to dreams of the underworld, yearn for every minute spent reviving my memories there.

No one comes into my room, henceforth. Over the cracked ceramic tiles, sounds of hooves can be heard as I prowl about—only later do I realize that they come from me. On the first full moon since my transformation began, I’m not surprised to glimpse two shadows positioned outside, before my window. Fever burns up my fingers as I march into the living room, leaving my door open. I turn the knob of our front door and join the shadows—Her creatures—outside.

One has the face of an old woman, flaps of skin dangling from her cruel, emerald eyes, while the rest of her skitters in the oily-black segments of a centipede. Her lips, thin and desiccated, are set in a firm line as she holds an obsidian spear. The other, a humanoid warthog with yellow tusks, heaves wet breaths over my skin, and reeks of old urine. His red eyes emulate the frenzy that rolls over my body. That is how I know I’m in the presence of kin.

It’s far into the night, yet Kana is stealing glances at me from behind the curtains of her room. I see her wipe tears off her sunken face, yet that gesture elicits no compassion in me. She must be too terrified to meet me outside, to try and make me stay. Her fear is nectar to my senses.

The fur on my curved legs glistens under the moonlight. There is beauty, in the way we carry ourselves as beings of anomaly. My vision seems heightened as I trot away from the empty house and its empty people. I follow Her creatures to the old baobab rooted in my neighbor’s compound. Its rough surface liquifies, and I cast no further glance to Kana when we disappear.

I am standing before Her, while the centipede woman and the warthog flank either side of me. My breath freezes to a stop as I take her in: sitting atop the throne, regal, watching me with a delighted, intense expectation.

The worms that form her hair make a wet, sucking sound as they secrete more slime. One of them turns red at the tip. My gaze is drawn to it as it falls and morphs into that which I’ve been craving. My knees buckle. I throw myself to the ground before her, looking up with the sheer adoration that fuses my soul.

“Make me your Fruit,” I whisper.