John convinced his grandson to take him on this trip even though Franklin had his doubts. John felt apologetic. He knew he was asking a lot. Franklin was a fine young man, and had always been a loyal and dutiful grandson, but clearly John’s progressive disease frightened him. John persuaded him this was his final opportunity to see the house where he’d lived as a child—“before my mind goes”—and so reluctantly Franklin agreed. It was a shameful manipulation. John felt embarrassed for the man he once was.

The old homeplace was near Duffield Virginia off Pattonsville Road. Scott County, deep into the southwest corner of the state. The population had always been small, and now was down to a tiny community of seventy-three, according to Franklin. He’d looked it up on wiki-something. John had lost the ability to use the computer. He didn’t miss it.

John couldn’t remember how old he was when his family left the house, fleeing in the middle of the night with time only to throw a few things into the car. But it had been at least sixty years. He’d been nine or ten. Maybe eleven. He’d never gone back, not until today.

His sister died a few months ago, and much to his surprise he discovered she still owned the place, and now it was his. How did that happen? He couldn’t follow the legalities involved. He hadn’t seen his sister in years. Were they estranged? Certainly, they’d been strangers. Was he being unkind? In any case the state was about to take the property for unpaid taxes. Let them have it—he certainly had no use for it. John just wanted one final look.

They had a map from his sister’s lawyer. They couldn’t have found the house otherwise. The road was gravel, dirt, and weeds. Franklin kept saying, “it’s a jungle in here,” and each time he said it John felt guiltier. Franklin’s vehicle had a high ground clearance, but it wasn’t designed for off-road travel. John lost his license some time ago and couldn’t share the driving. Although it was for the best he supposed he still resented it.

John was about to suggest they give up when Frankin cried, “There it is!” and stopped. “It’s only a few yards. We can walk the rest of the way. You can hold onto me just in case.”

Despite his misgivings, John could tell his grandson was enjoying himself. He was still at an age when inconvenience felt like an adventure. Franklin unloaded a backpack, snacks, and a powerful battery-operated lantern he bought especially for this expedition. He reserved a yurt for the night at the Natural Tunnel Park a few miles away. John was confused at first—he thought the word referred to a kind of drink. Then Franklin explained it was like a tent. He seemed quite excited about it. John didn’t want to sleep in a tent. Camping had never appealed to him, not even when he was a boy.

No doubt Franklin would want to see the Natural Tunnel itself, which William Jennings Bryan once called the eighth wonder of the world. Of course, Bryan had been a bit of a blowhard. Hundreds of thousands of years of a stream running through the limestone carved it out, and like every other natural tourist attraction in the U.S. it had its own Lover’s Leap, and a tragic story of star-crossed Indian lovers to go with it. Or he’d want to hike up to the Devil’s Bathtub, a natural depression in the bedrock full of water. Nature took multiple millennia creating these wonders and human beings spent fifteen minutes manufacturing semi-appropriate metaphors. John would remain back in the yurt during any such sightseeing if Franklin let him.

The land here was rampant with porous limestone, sinkholes, and caves, many of them hidden or undiscovered. You never knew when you might step off the trail and into a hole. John had no intention of risking any broken bones, certainly not at his age.

“Damn! No reception.” Franklin kept pushing buttons on his cell phone.

“Do we really need that thing?” Franklin gave John a cell phone for Christmas. It was still in its box in a drawer somewhere.

“If there’s an emergency, yes.”

“I guess we’ll have to avoid emergencies.”

John couldn’t see the house, but he couldn’t see a lot of things if there were trees or other distractions around whatever he was looking for. He counted on his grandson to lead the way. Instead, Franklin had John grab his left arm and they walked together. John wanted to say he wasn’t blind, at least not yet, but it seemed silly to fuss.

They kept away from the road’s deep ruts and pushed through thick growths of chickweed and bull thistle, button weed and spotted spurge. How come he could remember the names of all these weeds and yet so little of anything important?

A patch of gray ahead of them evolved into the side of a house with all the paint worn away, the structure difficult to distinguish at first from the overgrowth and the shadows among the trees. John couldn’t remember the original color, white or a light blue, but even back then the paint hadn’t been kept up.

So many places to hide, whether you were a victim or someone intent on doing harm. The leafy trees smothered the light. He imagined it always felt after sunset here. He didn’t know if his grandson kept a gun in his car—most of the locals did. John should have asked.

Like many older homes in the area the house dated from the Civil War. The house still wore the remains of the fancy gingerbread fretwork and medallions and eave brackets of that era, split and half-rotted. The brick and stone foundation was losing its integrity, splitting into its component blocks in parts. The ancient shutters were shredded or missing. The windows were all broken, reduced to black rectangles of rotted screen. The porch roof sagged several feet on one end and the porch floor itself had fallen onto the ground. Pieces of a shattered swing hung from rusty chains. The fence in front of the house was missing its rails, leaving a few posts covered in thick layers of vine.

John knew time had been the chief perpetrator here, but his eyes kept searching the greenery for evidence of others.

“Was that your family’s car?” Franklin pointed to the corroded skeleton of an automobile beneath a collapsed shed.

“No. Daddy drove us away in his Bel Air. That was grandaddy’s. Daddy always said he’d get it running someday.”

The warped metal roof of the house was rusted brown and there were large holes where sections had fallen in. The old cook stove sat in the side yard. John supposed someone had tried to steal it for scrap but given up because of its weight. Nearby the balcony which once hung from the second story lay spilled through the weeds.

“We only have a few hours before losing light. You’re not sundowning are you Grandad?”

John knew the term well but refused to acknowledge it in relation to himself. “I’m just fine.”

“Okay, I’m going to check inside and see if it’s stable enough to be in there. If we go in we should be quick about it, though. Think about what you want to see, if there’s anything you want to get, whatever you want to accomplish here. That’ll make things go faster. But don’t go wandering around.”

“Whatever you say.” John tried to keep the irritation out of his voice but didn’t think he succeeded, given the way his grandson was looking at him. He could feel his annoyance rising like a fever he could not control. Along with it was a rise in paranoia. He didn’t want to be left out here alone.

“I’ll be quick.” Franklin tested the boards of the porch before putting his full weight on them, then stepped side to side as if looking for soft spots. The front door stuck for a moment, but then he put his shoulder into it and disappeared inside.

John meant to ask his grandson if it was spring or summer. For the life of him he couldn’t remember. But asking such a question would have been a big mistake.

He was of two minds. His grandmother used to say that. But in his case one mind was sharp and clear and the other overflowing with bewilderment. John never knew at any given moment which one was going to show up.

With Franklin gone John could listen to his surroundings. The wind through the trees. The songs of small birds. He used to know his birdsongs. Not anymore. If there were larger animals around they were holding their peace.

Then the distinctive trickles and burbles of running water became evident. Of course. A branch of the Clinch River ran behind the house. He and his dad used to go fishing there. He was suddenly thrilled, and took a few steps in that direction before stopping himself. If he weren’t here when his grandson came out of the house the child would have a fit.

The river flooded a few times while they lived here, bringing water, and whatever was in the water, almost to the edge of the house. John remembered he and his sister being so excited to see fish splashing in their backyard, but Mother wouldn’t let them go near the flooded stream. He wondered if there had been worse flooding since then.

But they didn’t leave because of the flooding. They fled the house in the middle of the night because of something far, far worse. If John could only remember what it was.

“Okay, I think it’s safe enough,” Franklin said. “It’s more stable inside than it looks. We can’t take the staircase to the second floor—we’d fall right through—but the main floor should be okay.”

The interior looked nothing like the pictures in John’s memory. Stain patterns on the walls and ceiling resembled badly healed wounds. The checkered kitchen linoleum floor appeared vaguely familiar, like a kitchen he’d once encountered, but not lived with. The kitchen chair seats were caked in layers of fallen plaster. Vines grew down the kitchen walls from a rent in the ceiling.

For a moment he thought he saw his mother standing there, staring at a pot on the stove with a blank look on her face. It happened more than a few times. She’d forgotten what she was doing. After awhile Daddy took over the cooking. Both would be dead less than ten years later.

The walls were much closer than he remembered, and there was a bush growing in one corner of the living room. Spicebush, he thought. They used to grow outside the house and the berries tasted peppery.

A collapsed couch near the flaking brick fireplace appeared too filthy to touch. If it once belonged to his family John didn’t recognize it. Some sort of abandoned animal den was evident inside the fireplace, scattered small bones left behind. Either the animal itself or what it ate.

They shouldn’t be here. John was suddenly convinced.

Franklin was in another room, poking at things, looking for heirlooms John might want to retrieve. He was going to tell Franklin this might not be the right house, even though he was sure it was, when he saw the mirror standing in one corner of a shallow alcove off the living room.

His mother’s old dressing mirror leaned against a background of split and moldy wallpaper. He recognized the scrollwork around the bottom edge. When he was small he’d held onto that edge while his mother modeled some new dress she’d made. This might have been her sewing space, although his fragile memory told him the sewing room had been upstairs. Moisture had gotten into the silver backing creating mirror rot. He could see parts of himself, but the rest was shadow and distortion. From certain angles the mirror cast bad reflections across the room. Out of the corner of one eye he glimpsed things creeping from the walls.

He caught a peek of his head in an unspoiled spot in the glass. His hair looked crazy, and he hadn’t buttoned his sweater right. Usually, Franklin fixed those things for him. He hastily moved his palm across his hair and fumbled with the top of his sweater. Another hand came up behind him and brushed the hair off his right ear. He twisted around. There was no one there.

“So, did your family grab the important stuff when they left?” Franklin stood a few feet away.

“Pictures mostly, some jewelry and a few changes of clothes, whatever money was in my dad’s wallet. My sister and I each grabbed a favorite toy. I can’t remember what I took. By the time we reached my uncle’s house upstate I know I didn’t have it whatever it was.”

“Why did you guys leave exactly?”

How many times was his grandson going to ask him this question? “I don’t remember. But I know my folks had their reasons.”

There was soiled and sour-smelling clothing scattered throughout the downstairs. John didn’t think they belonged to his family. They looked a little too new. Some had gray and fading reddish-brown stains on them. There were numerous signs of squatters: candy wrappers and food packages, indications of a fire along one wall, women’s undergarments, pornographic magazines. There were long rips in the walls where scavengers had removed copper wiring or pipe. John started to pick up a plastic bag off the floor when his grandson told him to stop. “It might have had drugs in it, Oxycontin, or something worse.” John couldn’t remember what Oxycontin was but heeded the warning nevertheless. All this evidence looked several years old. The squatters were long gone.

“Just let me know when you’re ready to leave.”

John knew that meant his grandson was eager to abandon this pile of wreckage. “I won’t be long. I promise.”

Despite his grandson’s warning he wanted to go upstairs where his and his sister’s rooms had been. A taste of his childhood. A reminder of the rare things which brought him joy. But he didn’t dare try the mossy stairs.

In a back corner of the first floor, he discovered a sagging armchair in the middle of a vacant room, a place to sit and watch the house disintegrate at one’s leisure. A rotting pile of lovely old books made a smelly mound by the chair. He remembered his father had a small study where he liked to hide. Was this it? He would have liked to sort through these books to see what his father liked to read, but he was afraid to touch them.

John knew his father had stopped reading sometime before the family ran away from here. The reason he remembered was because it was such a dramatic change. Used to, John’s mother had to drag Daddy out of that chair for dinner or for most family activities. But after he stopped Daddy looked so sad. John overheard Daddy telling Mother he still liked looking at these old books and turning the pages, but he could no longer follow the sentences.

The bedroom by the kitchen had been his parents’. He was eager to see it. After the family left this house things were never the same. They’d moved around the South, losing much of what they owned along the way. He didn’t even have photographs of them.

The air in the room was dusty, the room dark, and it was difficult to tell which details were actual objects, and which the random effect of overlapping shadow. Jagged timbers poked down from the broken ceiling.

A portrait hung on the wall by the door. A woman’s body, but she had lost her face. Something had scrubbed at the paint until all her features were erased. He thought she might have been his mother, or his grandmother, but thanks to his failing memory she’d been demoted to the anonymous dead.

He often had trouble determining distances in the dark but today seemed worse than usual. Was that a wall or a shadow? As he stepped further into the room he was assaulted by an awful stench. The drapes sagged with mold. Corrupted bedding hung off the side of the blackened mattress like ruined folds of skin.

John took another step, and the floor sank an inch or so. He was suddenly having balance issues. This sometimes occurred, but usually in a safer setting. Everything felt soft underfoot. He looked down and was alarmed by the amount of seepage from the cellar underneath. The floor swayed as if floating. Things began to fall off the walls and slide toward him. He didn’t dare move because of the mess and the peril. He wanted to call for his grandson but at that moment he could not remember his grandson’s name.

Layers of wall began to fall, revealing the naked lathing beneath. The shadows painting the walls began to drip.

“Grandad, I don’t think it’s safe for you to be in here.” Franklin, of course. His name was Franklin. His grandson grabbed his hand and pulled him from the room. Glancing back, John saw the room was a terrible mess, but nothing extraordinary. Light was bleeding through tears in the window shades.

“Is it morning yet?”

“No, Grandad. It’s late afternoon. Sometimes the late afternoon light and the morning light look the same. I know that must confuse you, but it’s okay, really.”

They were about to pass the cellar door when Franklin grabbed the knob and tried to pull it open. John barely suppressed a warning scream. But the door was either locked or swollen shut. Good, he thought. Let it be.

He watched a memory leak out of the cellar door: his father shouting at him to run away, something tall coming up the cellar stairs behind his dad. But his dad kept blocking whatever it was so John couldn’t see. Then his dad shook his head back and forth until his dad’s face went away.

But Franklin wouldn’t give up. He kept twisting and yanking on the knob. John, anxious the door not be breached, though he couldn’t have explained to his grandson why, grabbed that sweet child’s arm and began to screech “no no no!” until his voice went thin.

“Please step back, Grandad.”

“Don’t tell me what to do boy!” John could feel the anger rising from his chest into his head. He wanted to stop it but could not. Franklin squirmed out of his grip and John almost fell. He stared at this young man. “Is it morning yet?”

“No, Grandad. It’s almost sundown. I think we should get you to the campsite.”

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong, but you’re getting tired. We’ll check into our yurt, get something to eat, and then a good night’s sleep. We can still come back here tomorrow if you feel you need to.”

“I sleep too much during the day. That’s why I get confused. That’s the problem.”

“Maybe. Maybe it is. We should go now.”

Franklin hurried John along the dirt road and into the car, but he couldn’t get the engine to turn over. He tried and tried, but all he got out of the vehicle was a rapid clicking sound. John sat quietly, afraid he might say the wrong thing.

“I always keep blankets in the car. You taught me that, remember?”

John did not. “I did? I’m glad I at least taught you something.”

“You taught me lots of things, Grandad. You’ve always been . . . so wise. I’ve also got two air mattresses. We’ll camp out in the house where there’s more room. Maybe the car will start in the morning. If not, we’ll figure something else out. Everything will be okay.”

John smiled and nodded but knew better. In his experience when someone says ‘everything will be okay’ it usually won’t be.

Franklin found a broom in a debris-filled closet and used it to sweep out the living room. John kept getting up and pawing through the more interesting bits discovered by the broom until his grandson persuaded him to sit in the kitchen. It was embarrassing, but John had just enough sense of himself to know it was necessary. His brain was filling up with wreckage, and sometimes he couldn’t find the right memories, or the thoughts he needed, because all that wreckage was in the way.

Every few minutes John stared at the cellar door. He kept seeing his father running up those steps, something tall and borderless following him from below. Unfortunately, it was the clearest picture he had of his father. It was a memory which threatened to erase everything else the man ever did.

Both his parents died when John and his sister were teenagers—first his mother and then his father. The disappearance of his mother’s mind had already begun in this house. In retrospect the evidence was clear. The same was true of his father, although his father was at least able to hang on until he got them out of the house.

They died hooked up to machines, having forgotten how to swallow or breathe. John didn’t really know how his sister died. He should have stayed in touch, but that was as much her fault as his.

They made their beds on the floor with the lantern between them. The dark came quickly, rushing up to the very edges of the lantern light. In recent years it had become increasingly difficult for John to perceive objects in the dark. In his eyes, things were either visible in his world or they were lost to the shadows. But he understood the shadows were still there, waiting.

Either because he was nervous himself or because he wanted to distract John from the demons which came to him most afternoons as the sun went down, Franklin began a seemingly endless monologue about his work at the bank, the young woman he was dating, possible plans and their alternatives, what he remembered about his grandmother (John’s wife, who had been fading so quickly from his own memories he barely remembered being married), and much more.

John interrupted. “It’s okay, Franklin. I’m feeling relatively calm.”

“Are you? I’m glad. We’re both okay then, aren’t we?”

“Yes we are,” John said, although he’d suddenly forgotten why they were here. His grandson had obviously wanted to go camping, but why? John was always losing the thread of things. It was becoming tiresome.

“Was it always this damp?” his grandson asked.

“Damp? What do you mean? Is it raining? I don’t hear any rain.”

“This house. It smells of damp. I know there’s a river nearby. But this floor? Doesn’t it feel—I don’t know—wet?”

John felt cold and tried to shake it off. “I remember the cellar always flooded. There were cracks at one end, and a cavity that went, well, who knows where it went? Did I tell you there were caves all around here?”

“You did. Water carves its way through limestone. Hundreds of thousands of years.”

“That’s right! They call that kind of landscape karst. That’s a new word for you, child! Sinkholes, caves, all kinds of cavities in the rock, and under your feet. Daddy said we got water in the cellar because of that, and rats too, all sorts of creatures living inside those caves.

“I used to hate that damp smell! It got into your head, and it made it hard to think straight. You had to make an effort to push your thoughts through. I’d walk around the house numb and not feeling much of anything. I felt rubbed out.”

Franklin stopped responding, and soon John could hear the boy snoring. But John kept talking. It comforted him to hear a voice, even if it was just his own.

John opened his eyes in the middle of the night and thought himself outside the house. The roof over his head was full of holes, and full of stars. Everything was creeping toward him. Everything his grandson had swept to the side was now sliding in John’s direction.

He twisted around and found Franklin sitting up on his air mattress, staring at the cellar door. “Franklin, are you okay?”

“Grandad, is that you?”

“Of course it is, son. What’s wrong? What’s bothering you?”

“Where are we? I have no idea where we are.”

“We’re. We’re.” But John could not speak because of the cellar door. Which was open. He hadn’t noticed it at first, but the door was now wide open, showing them the way into the emptiness beyond.

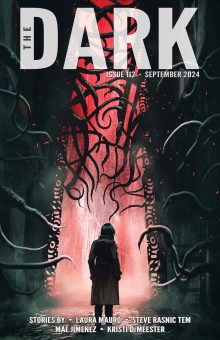

Originally published in Nightmare Abbey, Issue 4, 2023.